Demographics is Destiny

“Demographics is the iceberg of investment management; it is 90% underwater and moves quite slowly. The cycle is generational, so one cannot “trade” the process, but ultimately, it is the primary determinant of the economy.” - Harley Bassman aka “The Convexity Maven”, A Guide for the Perplexed, November 15, 2018.

Whilst the variables influencing economic growth are numerous and complex, there is a driver whose overwhelming influence has the final say; demographics. The significance of demographics in our economy is perhaps underappreciated, which is unfortunate given its impact can be found in almost all aspects therein; from economic growth and consumption, to interest rates and valuations, and even to the the velocity of money and the balance sheets of the the worlds central banks. Demographics is what ties it all together. What begins as a kickstarter for growth and prosperity ultimately ends up a headwind. Unfortunately, for the majority of developed economies this headwind has already arrived and is only getting stronger.

The population of the developed world is aging. Unlike that which we experienced throughout the second half of 20th century, whereby such economies enjoyed a growing working age population relative to children and retirees (support ratio), we face the opposite dynamic today. The largest generation in history is retiring and thus the number of retirees relative to workers is rising and is likely to only continue to do so over the coming decades.

Empirical evidence shows productivity, consumption and economic output peaks for workers roughly in their 20s-50s. Conversely, the contribution to GDP growth for the average worker roughly falls negative as people enter their mid-to-late 50s, and thus are no longer a contributor to economic growth. The below chart illustrates this relationship between age and economic output.

A falling support ratio for countries with an aging population should therefore be a powerful force slowing economic growth. This makes sense, as consumption (being the largest input for GDP) is largely based on age. The older we get, the less we consume.

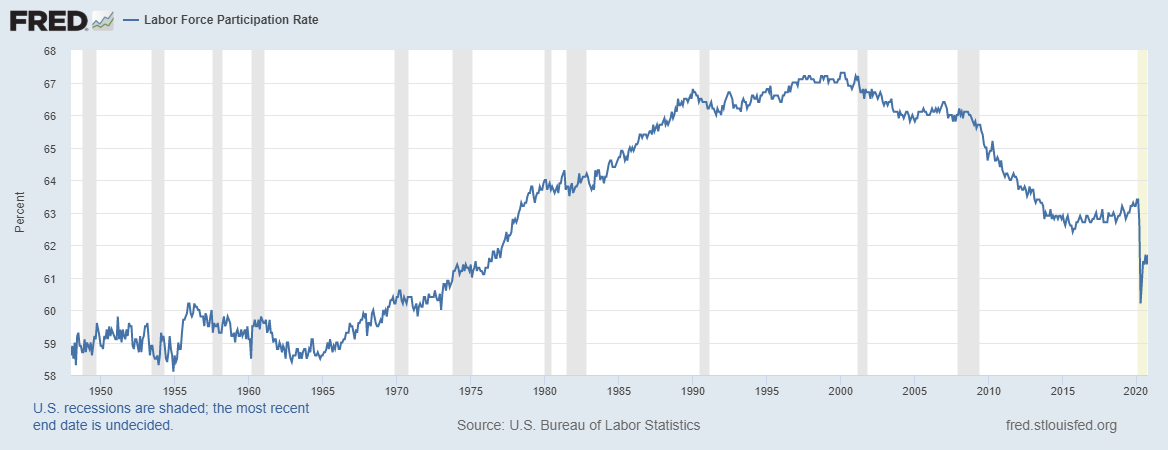

Using the United States as a proxy for the impact of demographics, we can see this dynamic in play. By simply looking at the labour force participation rate, the below chart clearly illustrates how the baby boomers, those born between 1946 and 1964 and are said largest generation in history, have been the primary source of the labour force as they began to enter the workforce in the 1970s and 1980s, and equally have begun to leave the workforce since the 2000s.

Source: St. Louis Fed

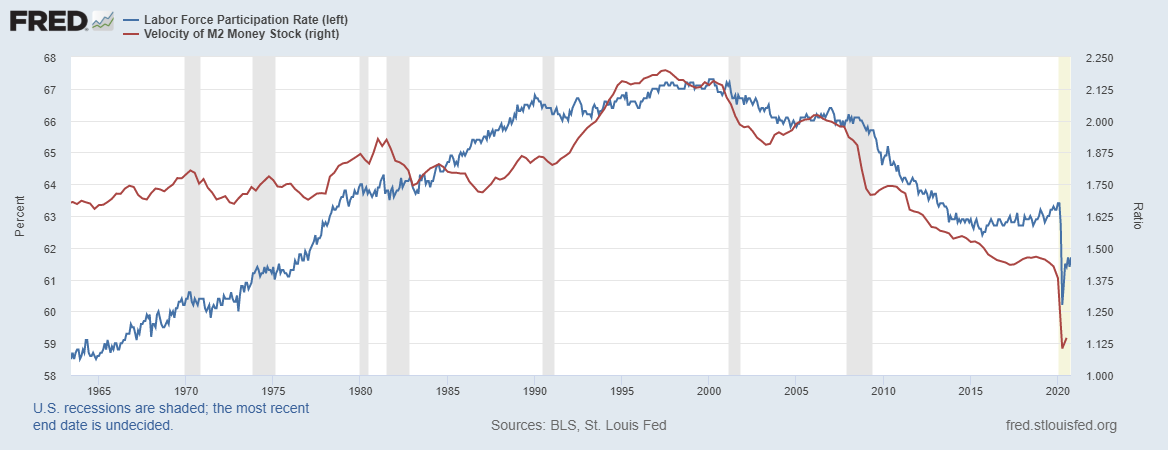

If we overlay the labour force participation rate with the velocity of money, which is effectively a measure of how many transactions take place in an economy and use this as a proxy for consumption, the relationship is clear.

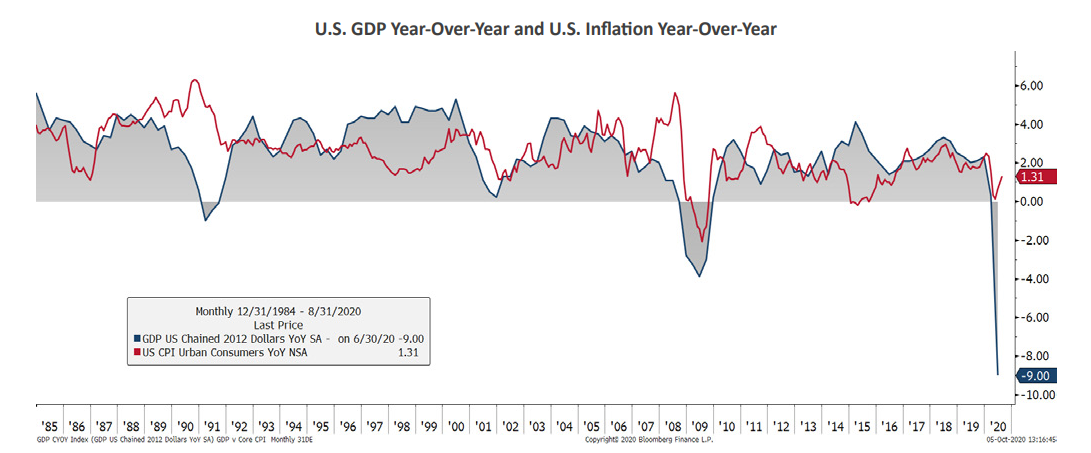

Indeed, the relationship between the labour force and economic output thus also becomes clear.

Demographics are clearly the primary driver of GDP growth and the velocity of money over the long-term. Correspondingly, these variables are two of the long-term drivers of inflation and deflation.

The impact of demographics on economic growth is clear, a favourable working age population will boost economic growth and provide inflationary pressures, whilst an unfavorable demographic makeup will impose deflationary pressures on an economy and provide a headwind to economic growth. You may have heard the phrase “demographics are deflationary”. This is inevitable.

As the baby boomers were peaking in their productivity, a by product of their economic prosperity was the bidding up of asset prices. What’s more, equity and property prices were historically cheap, affording them an opportunity to invest their cash flows in cheap assets during a time where their demographic impact of economic growth was perhaps the greatest in history.

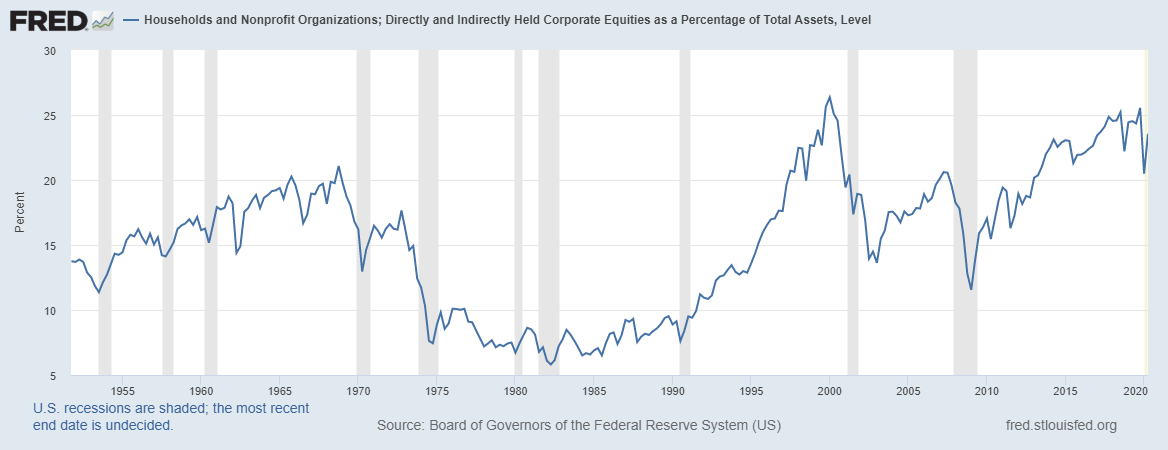

Equity valuations have largely been driven by demographics. As with demographics and GDP, the relationship between asset prices and demographics is clear. It is no coincidence the ratio of those of middle-age (i.e. 40-50) relative to the elderly (65+) peaked during the dot com bubble where equity valuations were at their highest.

Indeed, we can see that households equity holdings as a percentage of total assets also peaked at the top of the dot com bubble. As the baby boomers reached middle-age in the 1990s, their need to save for retirement in the form of accumulating assets grew.

It is not just asset prices influenced by demographics but interest rates too. Once again, the relationship between demographics and real interest rates is clear. There is a clear trend between a countries population growth rate and their real interest rates; favourable demographics boost economic growth, spur inflation and allow interest rates to rise; whilst inversely, unfavorable demographics are deflationary and result in lower real rates.

The same relationship between a countries fertility rate and its real yields is evident.

You will notice Japan’s positioning in both of the above charts. Their demographic profile is roughly a few decades ahead of the US, Europe and other developed economies like Australia. Whether they are the harbinger of what is to come remains to be seen. Since the 1950’s, Japan’s working age population has been declining relative to its retirees. This is beginning to plateau to a level it will likely remain at for some decades.

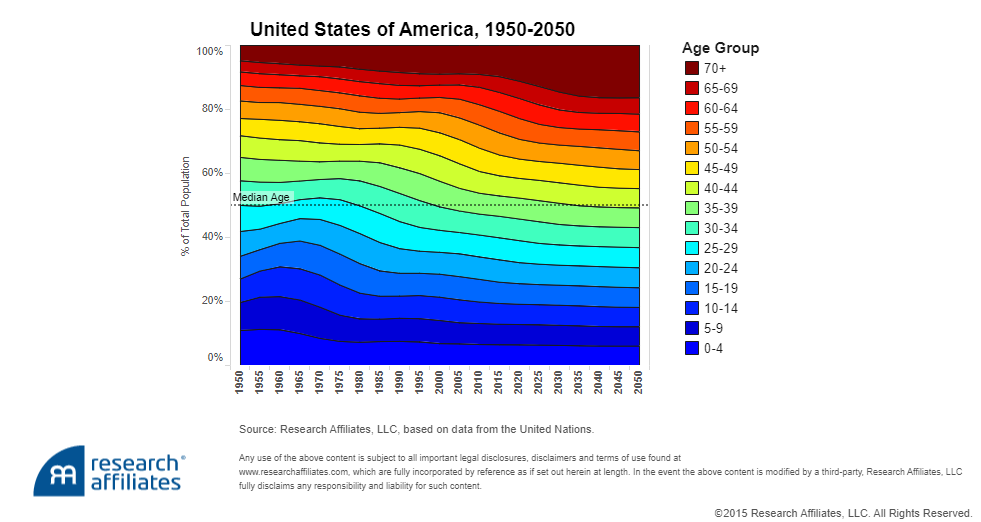

Source: Research Affiliates

If we compare this to the United States, we can see the US’s percentage of its population within their peak working years roughly peaked from about 1970-2000, a number of decades after Japan. The working age population of the US is too predicted to continue to slowly decline over the coming decades.

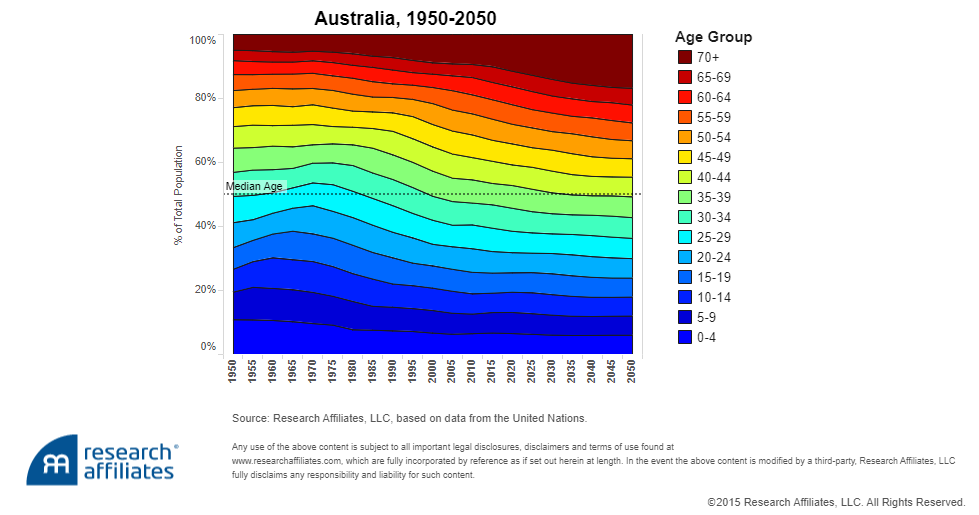

As another example, Australia are in a similar position to the US. So too are the majority of developed nations throughout the world for that matter.

It is clear then the demographic backdrop for the majority of the developed world is problematic. Taking Fredrik Nerbrand’s Grad-to-Granny ratio, a measure of how many people are entering the workforce versus how many are leaving, we can see that even in various emerging economies whose demographics are relatively strong (i.e. India, Brazil), the ratio is expected to decline over the next decade.

Source: Fredrik Nerbrand

The United Nations consider a fertility rate of 2.1 (i.e. roughly 2.1 children born for every couple) to be sufficient to maintain the current population levels throughout the world. Their forecasts of fertility rates over the remainder of the century for developed and emerging countries tell a story of stark contrast between the two. Demographics are clearly in favour of emerging economies.

What this of course means is most developed countries as a whole will experience falling trend growth rates in GDP, whilst emerging economies will on average receive a favourable boost to their economic growth. This is of course a generalisation and by no means is indicative of a changing world order, nor are all emerging economies the same.

Japan’s experience over the past 30 years certainly gives us insight as to what is to come for the rest of the developed world. The below chart illustrates this well.

A population whose majority is entering retirement will put downward pressure on asset prices and valuations. This is a double edged sword whose implications are significant. As life expectancies are continuing to increase, the baby boomers have been forced to try and generate sufficient wealth to be able to fund their retirements as they reach their retirement ages of 65-70. This has caused excessive risk taking and has seen US household equity holdings as a percentage of household net worth remain at levels near all time highs (refer to earlier chart). Likewise, it is no wonder the standard “balanced” retirement portfolio has nearly 80% of its allocation towards growth assets. Pension funds and retirees have had no option but to move up the risk curve in order to generate the required returns promised by these pension funds. As a result, we have all time highs in equity valuations, bonds and the lowest interest rates throughout recorded human history. The biggest and wealthiest generation in history is beginning to retire and as a result are needing to sell their assets to fund their retirement.

Such forces will eventually find their way into asset prices:

And given that nearly 80% of all household wealth is owned by those over 60, the implications of the holders of these assets needing to sell are clear. As the number of those needing to sell outweighs those needing to buy; prices have to go down, destroying the net worth of those needing to sell. Such a dynamic is somewhat self-reinfocing.

It begins to make sense why we have seen such extraordinary levels of monetary policy easing throughout the 2000s. Whether implicit of explicit, the expansion of the worlds central bank balance sheets is almost directly correlated with falling labour participation rate. Central banks need to do whatever they can to offset the retirees impacts on asset prices and consumption. Take the Fed for example:

The same dynamic can of course be seen in Japan (below) and most of Europe (not pictured). This is not a coincidence.

Given how underfunded most of the corporate and state pension plans are throughout the US, even though asset values are at all times highs, leads to the only logical conclusion that central banks and governments will be forced to print money and spend in order to fill the holes created by these demographic trends and their deflationary pressures.

So what are the implications of unfavorable demographics of the worlds developed nations. As discussed above, we are likely to see downward pressure on asset prices, at least to some extent. Retirees will have no choice but to be valuation indifferent sellers. This selling pressure will likely exacerbate market volatility, a dynamic only further accentuated by the rise of passive investing I have discussed in depth previously. As the boomers, who hold most of the assets are largely invested in active managers, while the millennials entering the markets are doing so via passive vehicles; volatility will result and accompany large and violent swings in prices both to the upside and downside. Such circumstances are likely unfavorable for the buy and hold investor as discretionary active managers are more likely able to take advantage of such asset pricing behaviour. Discretionless, systemic passive vehicles are not. Likewise, the tend of consistent market gains which we are so accustomed and we have seen in the US may be coming to an end, which of course is again unfavorable for the buy and hold investor.

If we look again to Japan as an example, we have seen since the Nikkei peaked in the early 1990s, basically any buy and hold investor who entered the market from the mid 1980s to 2000 would still be underwater or have only modest gains to show.

This does not mean equity markets have been devoid of opportunities. As we can see above, the Japanese stock market has essentially traded in line with the business cycle since the mid-1990s. Whilst unfavourable for buy and hold investors, such market conditions are able to be exploited for the astute active manager. I expect we will see similar equity market conditions within the US, Australia and other developed markets over the coming decades.

Will we see nominal interest rates enter negative territory in such places as the US and Australia following the deflationary demographic spiral that has led Japan and Europe to go negative? Perhaps. Whilst the Fed has explicitly stated they will not take the benchmark rates below the zero-bound, it is clear the demographic dynamic will do its utmost to make this happen as the two are inextricably linked (refer earlier charts).

As we have seen in Japan, with the Bank of Japan and the Japanese government doing all that is possible to spur economic growth and counteract the deflationary forces - with such measures including directly purchasing equities and government spending that has resulted in its government debt amounting to around 240% of GDP, almost twice that of the US, it is clear we will see similar levels of stimulus employed by the United States, Australia and Europe over the coming decades.

Source: TradingEconomics.com

Governments simply cannot afford of undertake a reset of its equity markets to an extreme degree as such events would destroy the wealth of those baby boomers who are retiring. Likewise, as we have witnessed in Japan, governments will do all they can to avoid the deflationary pressures of unfavorable demographics. One such measure to counteract such forces and spur growth we will inevitably see is the introduction of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC’s), a topic I intent to write further on in the future. Put simply, CDBC’s could effectively allow citizens to have bank accounts with their central banks in the form of digital dollars (or any such currency), blurring the lines between monetary and fiscal policy and effectively allowing central banks to provide printed fiat money directly into the hands of individuals, bypassing the traditional banking system. This would help to facilitate and encourage spending, particularly if targeted towards those in the most productive and highest consumption ages. Such measures would do well to spur the velocity of money and counteract the deflationary forces of an aging populace.

Likewise, we may see governments look to introduce favourable immigration policies in order to better their demographic profile and boost economic growth. Whilst potentially beneficial, without being too political the issue here is centers around how the baby boomer generation are generally distrusting of immigration, which as stated so well by Fredrik Nerbrand, “what they need the most they trust the least”.

Another such measure to address deflation would be for governments to simply buy all the student debt millennials have been forced to accrue due to the need for college and university degrees required to enter the workforce. Never before in history has a generation been forced to take on so much debt at such an early age. By wiping off such debts, the cash flow of millennials would of course increase and allow more room for spending for those in the age where consumption is more of a necessity.

So where does this leave millennials? Are we the unluckiest generation in history? Other than being forced to accumulate extreme levels of student debt, the millennial generation and those proceeding it are also facing historical valuations in just about every traditional asset class imaginable. Millennials will likely need to look outside the realm of developed market equities to find ways to accumulate wealth and save for their own retirement. Such opportunities do exist, entrepreneurship, cryptocurrencies and emerging markets with favourable demographic tailwinds are all areas likely to do well. So to are areas such as precious metals which will benefit greatly from the extreme amount of monetary debasement. It is a shame the market incentives have resulted in the majority of their retirement savings being directed towards passive investing vehicles. Whilst low cost indexing is of course an appropriate way to invest, most index products are almost exclusively allocated to the developed market economies and will not necessarily provide the opportunity for the younger generations to take advantage of such opportunities. The buy and hold approach that worked so well for the baby boomers is not likely to fare so well for the millennials.

Whilst the outlook may appear grim, there are opportunities to be had. Emerging markets are particularly attractive to a certain extent, given they are relatively cheap and many have favourable demographics. Such countries like India, whose median age is still in the 20s will enjoy a demographic tailwind going forward similar to that experienced by China over recent decades. I do not anticipate the current developed economies will be surpassed as the worlds superpowers by demographically favoured countries, what is more likely is the relative outperformance in terms of equity markets and economic growth of the emerging markets versus the developed. Such an opportunity should be taken up in earnest.

“Our main goal in presenting these results is to correct the common misconception that developed countries went through a “normal” period of high growth, as if we are entitled to fast-growing prosperity. In reality, the developed world is entering a new phase in which the low fertility rates of past decades lead to slow growth (in many countries, no growth) in the young adult population.” - Rob Arnott, Denis Chaves - Mind the (Expectations) Gap: Demographic Trends and GDP.