Emerging Markets: The Trade of the Next Decade

If there is one place I would recommend investors allocate their capital over the coming decades, it would in emerging markets and it would be an easy decision.

Largely tied to the fate of the US dollar, the underperformance of emerging markets relative to their developed counterparts may finally be ending. At their current valuations, emerging markets undoubtedly offer better long-term value when compared the US or developed Europe, and depending on how far down the emerging market risk curve investors are willing to go, generationally low valuations and growth potential can be found.

Starting with valuations, the stark difference in the CAPE ratio (10-year cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio) between emerging and developed economies is clear.y

If we drill down on an individual country basis and compare the top 12 most expense equity markets on a variety of valuation metrics to the 12 cheapest, it is obvious where the value lies.

12 cheapest equity markets. Source: StarCapital

12 most expensive equity markets. Source: StarCapital

Changes in market structure and the impacts of passive flows aside, there is no doubt that historically, such relative and absolute valuations presently associated with emerging markets have historically lead to superior performance. On this basis alone, I am willing to bet on EM.

So why are emerging markets so cheap and what will be the fundamental driver of their growth going forward? For the most part, the performance of the US dollar. During periods of US dollar strength such that we have experienced over the prior business cycle, this tends to put an inordinate level of stress on emerging market economies. Simplistically, the reason for this being the level of sovereign and corporate US dollar denominated debt held by a large number of emerging economies.

For countries with a large portion of their debt denominated in US dollars, a rising dollar relative to their domestic currency increases the burden associated with such debts as their purchasing power diminishes, increasing their debts interest costs and outstanding principal. This process of course works in reverse, as a falling dollar acts to increase the purchasing power of emerging economies, thus increasing their ability to repay their US dollar debts as their domestic currencies appreciate. The performance of emerging markets is largely dependent on the performance of the US dollar.

Unlike most developed economies whose debts are denominated in their own currencies of which their own central banks can print at will, emerging economies do not have such luxury and thus their economies prosperity is tied to the strength of the dollar. The reason emerging economies tend to borrow in US dollars comes as a function of them being able to access a larger amount of capital at lower interest rates.

Expanding on this dollar dynamic, a rising US dollar causes the domestic currency of emerging economies to fall and inflation to rise amid weaker economic growth. Contrary to a developed economy whose economic growth is generally associated with inflation, being beholden to foreign denominated debt reverses this dynamic. Higher inflation results in the central bank needing to raise interest rates and sell their foreign exchange reserves to defend their currency from hyperinflating, which acts as a further headwind to economic growth and exacerbating this dynamic in a self-reflexive manner. These countries are unable to simply print money to monetise the debt, as is commonplace in developed countries whose debt is denominated in their own currency. The governments will then look to use fiscal policy as a means to stimulate, resulting in increasing budget deficits at the same time foreign and domestic capital flees the country for a safer alternative to preserve wealth, resulting in a negative current account balance along with a budget deficit. Such are the risks with emerging economies that some such situations as described above have resulted in hyperinflation (look to Argentina and Zimbabwe as recent examples) and economic devastation. Of course this process varies from country to country as not all emerging economies work in this manner. Some are better equipped to deal with this process than others.

Of course these dynamics work in reverse too when the dollar is falling and create an economic tailwind that results in strong economic growth and asset price appreciation generally superior to developed markets. As the domestic currency strengthens, inflationary pressures fall, allowing the central banks to lower interest rates whilst the economy is booming, spurring lending and reinforcing growth. At the same time, the governments are not required to run budget deficits, nor are the central banks required sacrifice their foreign currency reserves and run current account deficits to defend their currencies. You could almost think of a rising dollar as a form of quantitative tightening for most emerging markets, whilst a falling dollar could be considered a form of quantitative easing.

Therefore, for one to be willing to bet on the outperformance of EM relative to US equities, one must have a bearish outlook for the dollar. My expectation over the next business cycles is indeed a cyclical bear market in the dollar. This is something I will discuss in greater detail in the future.

The dynamics described above are why it is important to consider all the various risks associated with emerging markets when selecting potential investments, along with assessing the ability of each economy to be able to deal with such risks. From a top down perspective, several important factors one must consider when analysing potential emerging market opportunities are discussed as follows.

GDP growth and demographics: The most obvious and important input to economic prosperity. The developing world accounted for 49 per cent of world GDP in 2010 and is expected to reach 60 per cent by 2030. I have discussed how demographics impact economic growth in detail here, and selecting EM countries with favourable demographic trends is an important consideration. Emerging markets contain the majority of worlds millennial demographic, a huge productivity advantage when compared to the aging developed world. According to 13D Research, “millennials now number 1.8 billion globally, about a quarter of the world’s population, and 90% of them live in emerging economies. Chinese millennials alone (351 million) outnumber the entire population of the US. But the important number to watch is the proportion of millennials relative to a country’s overall population. Standouts in this category include Bangladesh, Vietnam and the Philippines.” From a demographic perspective, India represents a fairly safe bet.

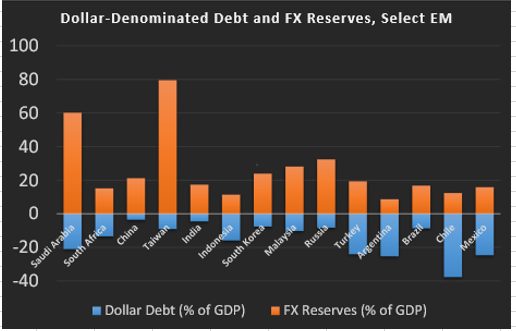

Debt: Another obvious consideration. Those select EM countries who have a lesser reliance on foreign currency denominated debt will of course be less tied to the performance of the US dollar. As detailed in the chart below from the excellent Lyn Alden; China, Russia, Taiwan, India and South Korea compare favourably in this regard.

Trade balance: A very good representation of a countries global competitiveness and outlook for their currency. Many EM countries are reliant on their exports to spur economic growth, but in doing so are vulnerable to falling international demand for said exports. Whilst not being an emerging market economy, Australia is a good example of a country whose reliance on exports (in this case primarily to China) is key to their economic growth. However, those countries with trade surpluses are generally more reliant on globalisation and international trade to support their economy, whilst those who run trade deficits are more self-contained and less reliant on their exports to support growth. Looking at those EM countries with a positive trade balance relative to their GDP is important. Russia, Singapore and Taiwan are some such positive examples.

Foreign exchange reserves: The best indicator of how well a country will be able to defend its currency during times of a strong US dollar. Countries with large FX reserves will be better equipped to do so during such times. The following charts provides an illustration of several EM countries and their US dollar denominated debt (% of GDP) along with their FX reserves (% of GDP). Again, as discussed above, China, Russia, Taiwan, India and South Korea all compare favourably in this regard.

Source: Lyn Alden Investment Research

The following chart shows FX reserves of the worlds most prominent developed and emerging countries (as of mid-2020):

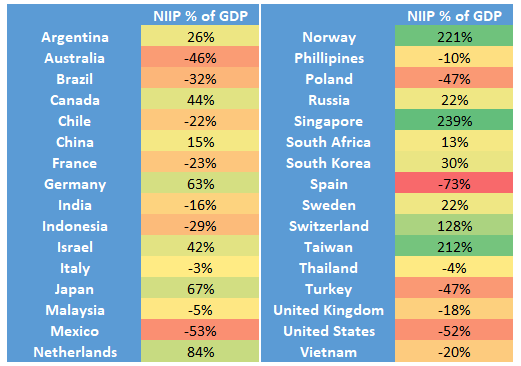

Net international investment position (NIIP) as a % of GDP: This measures the difference between the the amount of foreign assets held by one country less the amount of its assets held by foreigners. A country with a strong NIIP will own more foreign assets that foreigners own of their assets (a consequence of running trade surpluses) and will benefit from the investment income for these foreign asset holdings, whilst also being less exposed to the risk of foreigners selling a large amount of their assets at any point in time. This is an important consideration as the financial markets of many EM countries are invested in to a large extent by foreigners, and thus are handcuffed to the capital flows of these foreign investors. The following chart illustrates the NIIP as a % of GDP for the worlds most prominent developed and emerging countries (as of 2019), with Taiwan and Singapore being two of the EM standouts.

Of course there are many other factors to consider in addition to those listed above, those I have described are several of the primary factors one should assess when looking for potential emerging market investments. One final important consideration worth detailing is how the price of oil can impact an EM economy. Given that many EM countries are either oil exporters or importers, their future prospects can be somewhat tied to oil. For example, Russia remains one of the worlds largest oil exporters, with most of Asia being oil importers. As a result, a bull market in energy would bode well for Russia, resulting in a surge in exports and thus a strong current account surplus, whilst such a scenario would somewhat hinder countries relying on importing oil, as this would require them to run current account deficits to meet their demand needs.

From a technical perspective, the MSCI Emerging Markets index has formed a huge wedge patter dating back nearly 20 years. It appears to be finally breaking out in a bullish manner which would likely point to EM outperformance moving forward.

On a shorter-term perspective, emerging markets are looking overbought and in need of a rest. The reflation trade dominating markets since early November has resulted in impressive performance in EM, however, we are now beginning to see negative divergences in RSI and money flow, along with DeMark 9 and 13 sequential sell signals on both the daily charts (below) and weekly charts (not pictured). As I will discuss further below, a pullback in EM would likely offer a good entry point.

Source: StockCharts.com

On a relative basis, the long-term downtrend relative to US equities looks to be finally finding a bottom and setting up a reversal of trend. Significant bullish divergences in both RSI and momentum (as measured by price relative to its 200 day moving average à la Michael Oliver of Momentum Structural Analysis) seemingly confirm this notion. A confirmed breakout of the downtrend line (of which EM has just been rejected) would be an excellent indicator of EM’s outperformance relative to the US.

Whilst EM has performed well of late, it is clear we are yet to see the reversal in trend of US equity outperformance. When this finally occurs, EM will in all likelihood reap the rewards. However, I do have my immediate concerns. As I have previously discussed here, I do believe the dollar is oversold and is likely due for a counter-trend rally. Sentiment and speculator positioning towards the dollar is rarely this negative and such similar scenario’s in the past have generally lead to some form of dollar rally. “Dollar milkshake theorist” and dollar bull Brent Johnson noted as such on twitter recently.

Likewise, with EM up roughly 20% this quarter, a consolidation or pull back would be healthy and encouraging. If this would occur it should represent a good buy-the-dip opportunity for long-term investors looking to enter the EM trade.

In terms of gaining exposure to EM, for the average investor I would advocate for a core-satellite approach, utilising a simple managed-fund or ETF (such as EEM) as the primary vehicle with several country specific holdings with a lesser exposure for which outperformance may be expected. The problem with most emerging market ETF’s is their market-cap weighting, resulting in China constituting roughly 40% of most ETFs. As a result, most emerging market index’s are in effect predonimantly a China internet play. Given the risks associated with EM and their volatility, I believe active management to be the best approach given a managers (potential) ability to deal with said risks and diversify away from the Chinese internet companies, and who are be better equipped to take advantage of the value available within emerging markets.

In terms of individual countries I like as satellite plays, Russia, Singapore, South Korea and India are my personal favourites and I would look to invest in these country specific ETFs. I plan to detail my thesis behind these specific countries in the future. Depending on how far along the EM risk curve an investor is willing to tread, once the outperformance of EM versus US begins, such areas as Latin America, Iran, and Africa would likely be the best performers.

The rotation trade has performed well of late, but is perhaps overbought in the short-term, especially if we see a dollar spike, I do believe any dips in EM should be bought into for the prudent long-term investor.