Inflation: Catalysts & Consequences

With so much discussion of late revolving around the potential paradigm shift to a structurally inflationary environment moving forward, what better to do than throw my hat in the ring. This articles encompasses the inflationary forces of today as well those moving forward, whether they will prevail against the current disinflationary backdrop and the implications if this is indeed the case.

Inflation is a tricky topic to discuss given its broad definition and applicability among different people. Whilst we have largely lived in a disinflationary world for the past 40 years in terms of consumer prices, monetary inflation in terms of asset prices has skyrocketed. This has resultingly driven the wealth inequality and political divide to breaking point.

Traditional consumer price inflation itself is not applicable to all individuals, but rather has been a tale of two indices. The baby boomers, who as a group hold the majority of financial assets and real estate have been the biggest beneficiaries of this consumer price disinflation and asset price inflation. On the other hand, though the younger generations too have benefitted from consumer price disinflation in many areas such as technology, they are yet to accumulate financial assets or real estate to the same degree to have benefitted from monetary inflation. Additionally, they have arguably experienced consumer price inflation in many areas. Unaffordable housing, rising daycare costs and school fees are some such examples. Demographics is a powerful force of which I have written about previously.

Source: INTL FC Stone

Regardless of this divide, what can be agreed upon is the presence of several structurally inflationary tailwinds going forward, and, if they are to take hold of the economy, then what we will experience over the coming decades will be very different what was experienced in recent times. Investors must prepare for such a secnario. However likely or unlikely it may be, consumer price inflation in its oldest form could be making a comeback.

The Case For Inflation

The reasoning behind the ever increasing view toward an inflationary future is plentiful and justifiable. I will attempt to detail these inflationary tailwinds that could lead to a structural shift toward an inflationary future, beginning of course the most prevalent: the broad money supply.

The Money Supply

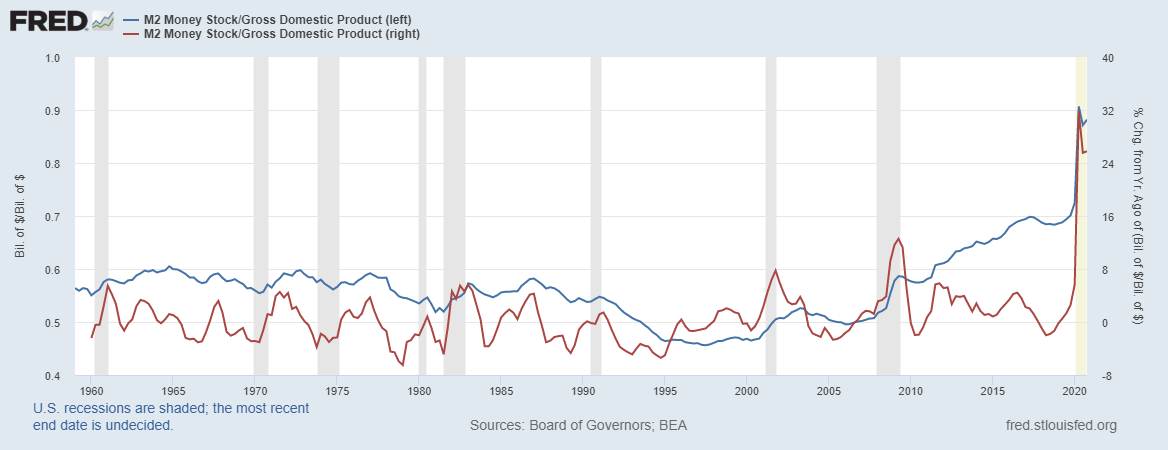

When in comes to the money supply and inflation, what matters is the broad money supply, or M2. We all know by now the unprecedented growth in the broad money supply since the onset of COVID-19. This extraordinary growth has become the means of explaining the swift rebound in asset prices. Whether the growth in the broad money supply is the sole perpetrator is up for debate, what is not though is its impact on the economy and equity markets over the past 12 months.

Source: St. Louis Fed

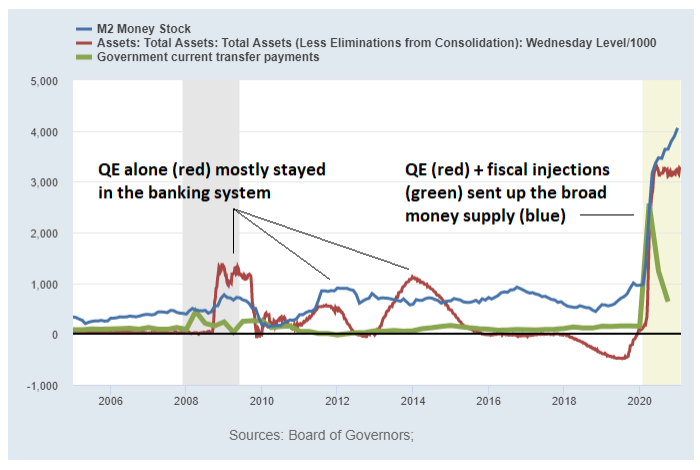

Money can be created in two ways; the traditional means via commercial bank lending or via direct monetization of newly issued federal debt. Up until recently, it has been the commercial banks who have been able to claim sole responsibility for the growth in the broad money supply. The notion that quantitative easing (QE) conducted by itself is money creation is false. The Federal Reserve and other central banks have the the ability to influence the base money supply (M0), but not the broad money supply. They can lend, but they cannot spend. What must be understood is commercial banks create money via fractional reserve banking when lending occurs between said banks and consumers and businesses. QE is a means of capitalizing the banks, allowing them further scope to be able to lend against these freshly printed reserves with the central banks. QE is effectively just a swap of government bonds for central bank reserves; unless lent against the two are negligible. Getting banks to lend is what increases the broad money supply.

Unlike the Fed, the Federal government does have the power to spend. If the central banks and governments work together, they are able to rapidly increase the base money supply and the broad money supply. This is what many believe will be the impetus for a return of secular inflation; central bank financed fiscal spending. Many believe this is in fact already the case. The great Russell Napier, who himself has been a deflationist over recent decades is now championing the inflationary paradigm shift. His belief is due to governments now stepping into the realm of guaranteeing bank credit and their direct monetization of the government debt, both tools we have seen various governments employ over the past 12 months, is a means of governments and central banks finally entering the realm of true money creation.

If the central banks are directly funding government spending and outright guaranteeing loans made by banks, then this is money creation and has no doubt played a role in the expansion of the broad money supply. If such a fundamental shift is the norm going forward then in my mind, I do side with Russell in that this would be structurally inflationary. When a central bank is mandated to guarantee bank loans or does so on its own accord, or directly monetizes the federal deficit using freshly printed currency, then it is in the business of creating money. Consumers will spend free money.

We can see how this relationship has played out in the past. The chart below from Lyn Alden is the perfect illustration of how growth in the broad money supply over the past 15 or so years has not been a function of QE or government spending in isolation, but rather is a result of a combination of the two.

Source: Lyn Alden Investment Strategy

With the dynamic of central bank funded money creation, the Fed and government are able to rapidly increase both base and broad money without crowding out the private sector (which would generally occur when governments run large fiscal deficits funded by the private sector) or being restrained by the lending practices of commercial banks.

Going forward the question then becomes, how does the increase in broad money supply filter through to traditional consumer price inflation, or will it simply continue reinforcing asset price inflation. The issues with QE were (and still are) that the money printed by central banks was never able to leave the banking system as commercial banks did not make additional loans proportionate to their increased central bank reserves. As a result, QE has not historically increased the broad money supply or found its way into the hands of consumers. What is potentially different this time is that by definition, an increase in the broad money supply largely means this money is beginning to find its way into the hands of consumers. It now rests more generally in households and businesses, notably smaller businesses who are more inclined to spend for productive reasons.

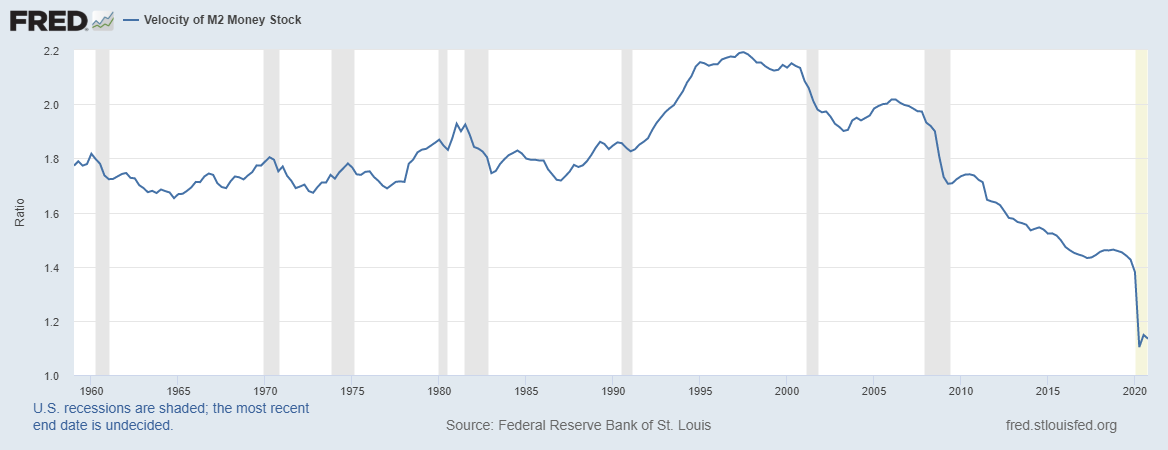

The gauge for how the broad money supply will impact consumer prices is of course the velocity of money. Put simply, the velocity of money is the rate at which money is exchanged in an economy through transactions between lenders and borrowers, buyers and sellers. Whilst the relationship between money velocity and CPI is clear, unfortunately, M2 money velocity still remains near its lowest point in over 60 years:

Source: St. Louis Fed

Many believe the velocity of money will pick up once the COVID-19 lockdowns and restrictions subside, allowing consumers and businesses to finally spend and releasing a wave of pent up demand that ought to provide a reflationary tailwind to CPI. To a certain extent, I do not doubt this will be the case.

Fiscal Dominance & Political Instability

History suggests that paradigm shifts are quite often reinforced by political shifts. As I touched on above, we are entering an era of central bank financed fiscal spending. In all likelihood, Congress will no longer be constrained in their spending efforts to what they can do, but rather what they are politically obliged to do. The populist movement is real. Driven in large due to the error of quantitative easing, easy monetary policy and the continuous central bank bailouts of Wall Street at the expense of Main Street, it appears as though such measures as regular payments to individuals, universal basic income and straight up MMT are indeed slowly becoming the norm. The seeds of fiscal dominance have been planted.

We witnessed the power of fiscal spending during the height of the pandemic, when despite of the temporary shutting-down of the economy, personal income in fact went, a result of the reliance on government transfer payments and stimulus:

Source: St. Louis Fed

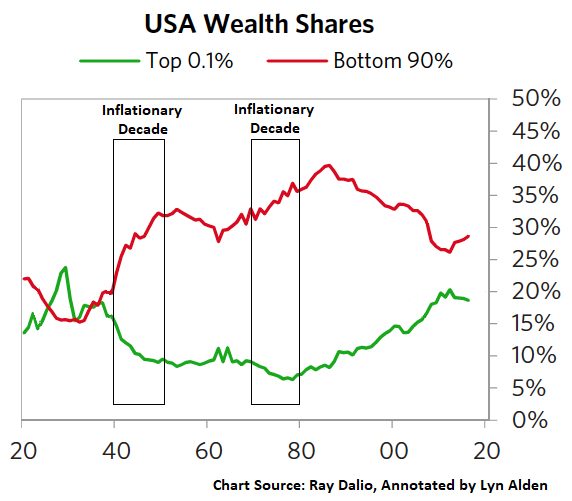

One huge appeal of fiscal spending is its potential ability to bridge the wealth gap via inflation. If fiscal dominance does eventually lead to inflation, such inflationary periods over the past century have seen large declines in the wealth divide among the rich and poor.

Source: Ray Dalio, Lyn Alden

Fiscal dominance and MMT is easily justified by politicians. Central bankers have tried endlessly to get inflation; it is a palatable solution to the wealth divide. Direct payments to individuals is the easiest and most assured way to get the money into the hands of individuals who actually have a higher marginal propensity to consume. QE alone does not and has not done this. If fiscal dominance is not able to increase the velocity of money in today’s economy then nothing will.

Other Inflation Catalysts

Whilst my belief is that the single largest determinant of a shift to a period of structural inflation will be fiscally driven spending and payments to individuals, there are several other notable inflationary catalyst worthy of discussion.

De-globalization/protectionism

One of the most deflationary forces of the past 40 years, globalization has seen the US forfeit its entire manufacturing sector, favoring capital at the expense of labor. De-globalization, protectionism, tariffs and trade barriers would go a long way to reverse this trend.

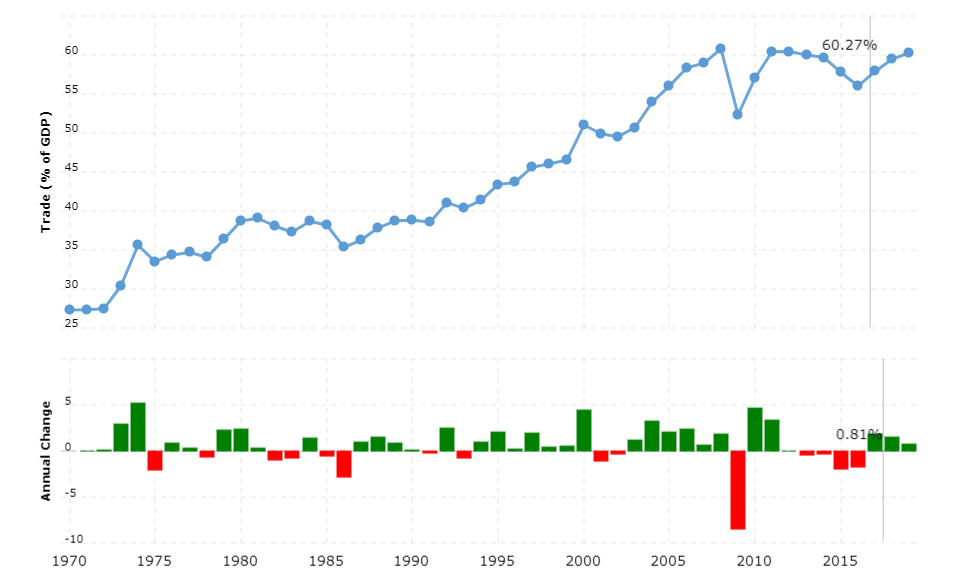

World trade as a percentage of GDP peaked back in 2008 and has been stagnant since, as the chart below illustrates.

Source: MacroTrends.net

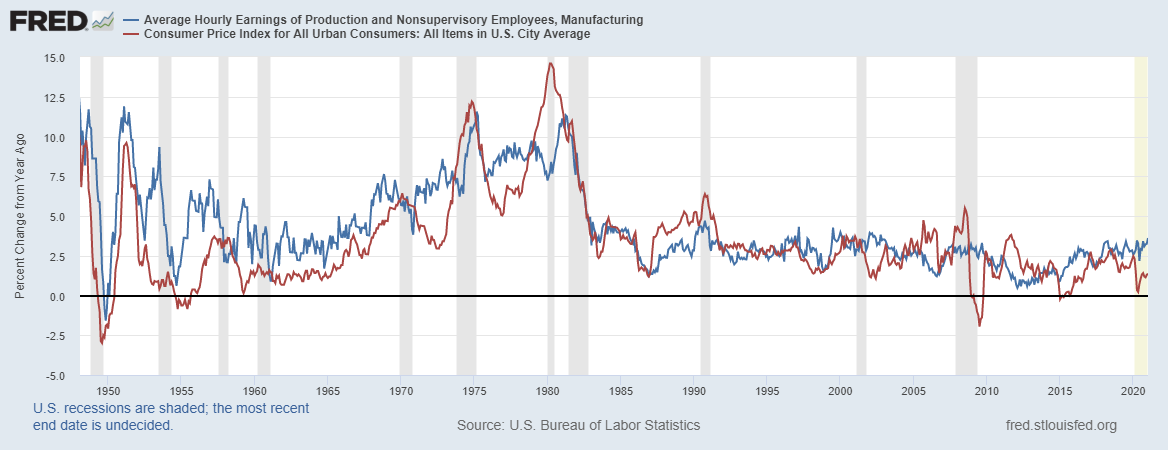

Should we start to see this trend reverse course, it would go a long way to once again turn favor to labor at the expense of capital. The past twelve months have perhaps been the catalyst that an over-reliance on foreign supply chains does have consequences. Indeed, we are already beginning to see the Biden administration implement these very measures. Protectionism would transfer power back to the younger workers and spenders, forcing companies to raise wages and thus provide a strong tailwind for a rise in consumer price inflation. This is perhaps one of the most important factors likely to lead to an inflationary regime; in order for a sustainable rise in inflation to occur, then wages must be a primary driver, and protectionism and de-globalization could indeed help to push up wages.

Source: St. Louis Fed

Likewise, regionalization of supply chains would resultingly need them to be shortened, brining about further increases in the price of input costs, which in turn would be a cost borne by the consumer through higher prices and thus higher inflation.

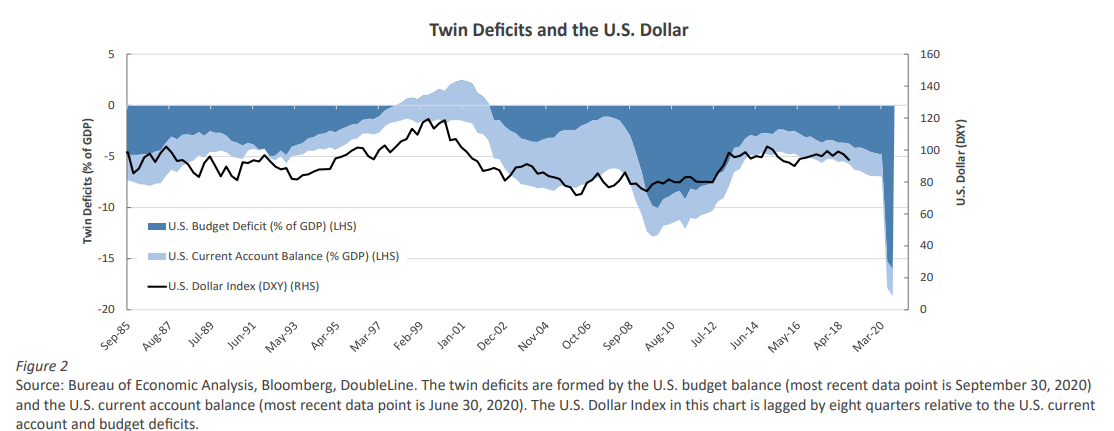

US dollar bear market

A weakening dollar would too be somewhat contributory to an inflationary paradigm shift. Firstly, it is my expectation that the falling dollar environment we have entered post March 2020 will continue over the long-term.

Considering the US runs one of the world’s largest trade deficits relative to its economy, a falling dollar for a net importer would result in rising import prices for both businesses and consumers. This in turn contributes to rising input costs and thus higher prices. A falling dollar is also generally bullish for commodity prices.

However, it is worth noting that for the dollar to have a significant impact on inflation via rising import prices, it would need to be a substantial move downward, and any inflation would largely be contained within goods, as goods are imported whilst services are not. Goods prices only make up around one-third of CPI.

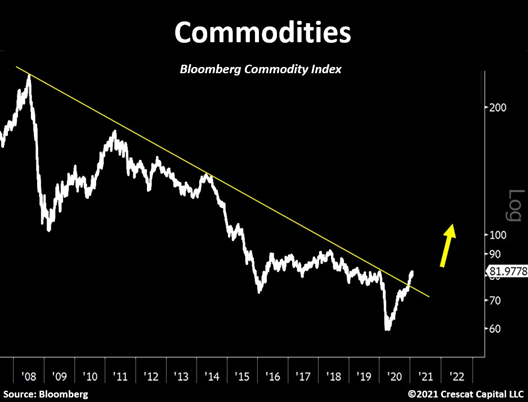

Commodities bull market

The past decade has not be favourable to commodities. Since 2008 the Bloomberg Commodities Index has more than halved, driven by a period of persisting commodity oversupply providing a deflationary force for consumer prices. Commodities relative to financial assets are near their all time lows. Were we to enter a period of continued commodity scarcity and thus a commodity bull market, this would no doubt provide an inflationary tailwind going forward.

Source: Crescat Capital

The lockdown driven supply restrictions have contributed to the rapid rise in things such as copper, lumber and oil over over the past few months. For this commodity bull market to be sustainable going forward, we would need to see a pick-up in the demand side of the equation along with continued supply shortages. In regards to the latter, we have seen commodity producers massively cut capital expenditures to cope with the COVID driven fall in demand. Continued underinvestment would certainly support this dynamic.

Another factor at play is how investors will likely seek out hard assets such as commodities to provide a source to protect their purchasing power in the event of inflation. There is also a political tailwind for commodities, with the Biden Administration's proposed infrastructure package set to contribute the increased demand for more industrial commodities, as well as the shift to a green economy I will discuss below.

Green Energy & ESG

Whilst not an immediate inflationary catalyst, the focus on green energy and ESG is a trend that is only gaining in popularity, acceptance and political support. The move towards green energy policy will undoubtedly put upward pressure on commodities such as copper, lithium, nickel and cobalt, all used in large as part of the production of electronic vehicles. Indeed, as noted recently by Knowledge Leaders Capital, “electric vehicles contain 183lbs of copper compared to 43lbs for combustion vehicles, while wind turbines contain 800lbs of copper”.

With this shift toward green energy and the Biden administration making green energy policy a priority, we have since seen copper explosively breakout to the upside of its pennant patter dating back over a decade; very much a long-term bullish technical sign.

Source: StockCharts.com

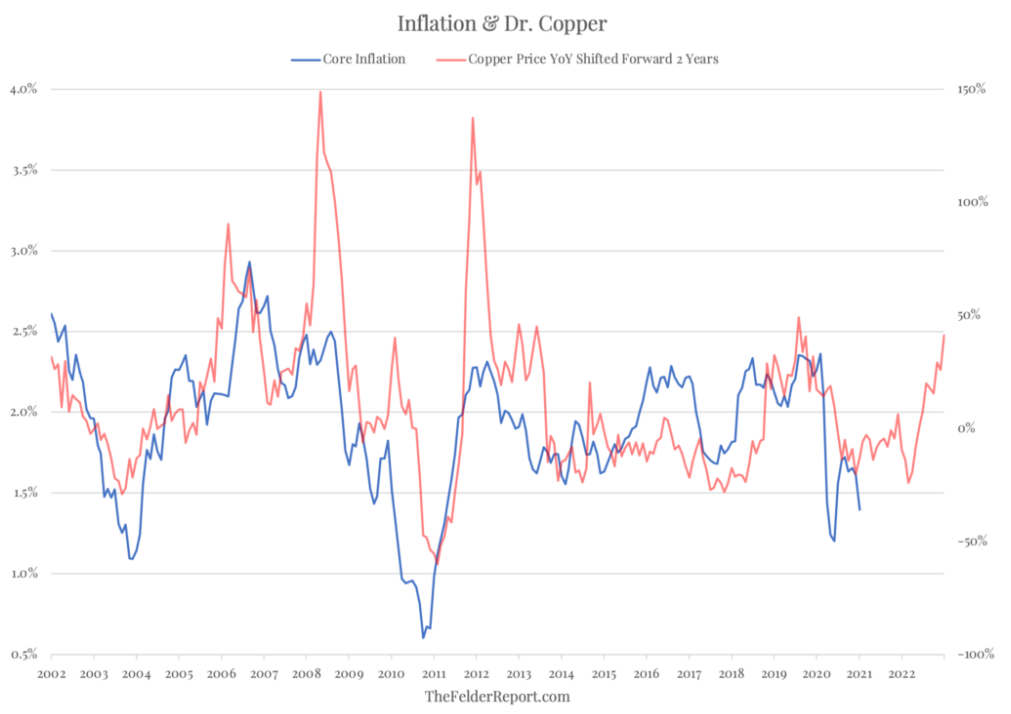

Dr. Copper is prescribing inflation.

Source: The Felder Report

What’s more, “green energy policy will seek to raise fossil fuel prices in general (either through taxes, a reduction in subsidies, or other hindrances to new production).” The shift toward green energy will indeed help provide the demand for a sustainable commodity bull market.

Not only does a green energy and ESG movement provide a inflationary tailwind via this increased demand for commodities, but it also plays a role it restricting the investment of capital in less environmentally friendly resources like oil. As we still remain a long way off completely removing our reliance on oil and energy, supply shortages via insufficient capital expenditure will only add fire to the supply driven rise in oil and energy.

Pent-up demand

The post lockdown release of pent-up demand is what many are pointing to being the catalyst for a coming inflation. Due in large to the fall in demand for many goods and services consumers have not needed nor been able to consume during lockdowns over the past 12 months, the supply shortages for many goods will of course only exacerbate the effects of a release in consumer demand once spenders are allowed to spend. Cinemas, airlines, hotels and resteraunts are some such examples of areas where this pent-up demand will funnel.

Source: St. Louis Fed

We have seen the savings rate as a percentage of gross domestic product spike to historic levels, as such, if we were to simply see savings to return to its average over the past couple of decades, this spending would no doubt trickle down into consumer prices. Whilst it may only have somewhat of a temporary effect, some form of demand-pull inflation ought to ensue as a result of a release of this pent-up demand.

Central bank digital currencies

The introduction of central bank digital currencies (CBDC’s) is perhaps the most important factor at play in regards to completely changing how the elected officials are able to generate inflation. Whilst the act of governments guaranteeing bank credit and central bank financed fiscal spending are the first steps into the realm of MMT style direct payments to individuals, the introduction of central bank digital currencies will take this entire dynamic a step further to the point where the entire financial system we know today would be upended.

CBDC’s would completely destroy whatever remains of the proverbial wall between fiscal policy and monetary policy. This is without a doubt an inflation game changer. If we are to see the introduction of a digital currency that can be directly provided to individuals via the Federal Reserve, this would allow the central bankers stimulus tools beyond anything seen today. They would have the ability to directly give money to certain people they deem more likely to spend, charge different types of people different interest rates depending on their spending habits, punishing savers with lower or negative interest rates in order to influence consumption. The entire commercial banking system and traditional means of money creation would be bypassed. This would put the Fed into the true money printing business and no longer be tied to the banks inability to lend and increase the broad money supply despite their massive QE programs.

Such measures undoubtedly would be abused and be an intrusion on private freedom, but are nonetheless likely and seemingly represent the culmination of the wrong headed policies of central bankers we have seen now for decades. None of the currently available tools at their disposal would allow them to micro-manage in the way a central bank digital currency could. The likely outcome will be inflation beyond what the central bankers bargained for. Bill Campbell opined the introduction of central bank digital currencies would be akin to opening Pandora’s Box of unintended consequences.

Average inflation targeting

The Fed has failed to meet their prescribed 2% inflation target every year since originally mandated in 2012. A recent shift in how they will attempt to reach this target is a signal of their increased willingness (or desperateness) to create inflation. As opposed to aiming for their traditional target of 2% annual inflation, they will instead now attempt to create average inflation of 2% annually. This subtle change is significant.

Average inflation targeting affords the Fed the ability to overstimulate the economy (as if they weren’t doing this already…). Nonetheless, this policy shift allows even more scope for their new forms of stimulus by way of directly monetizing the MMT style fiscal stimulus described above.

Incrementum AG detailed why this new inflation targeting policy is important in a recent report; “previously, if the economy had an inflation rate of 1.5% in year 1, then in year 2 the Federal Reserve would start from scratch in its attempts to reach 2%, and it would still aim for a 2% inflation rate in year 2 regardless of what occurred in year 1. However, under inflation targeting, the Fed can use the difference of 0.5% from year 1 to exceed the inflation target in year 2 by just that amount. Even with an inflation rate of 2.5% in year two, the Fed would still have met its inflation target. Where it would otherwise have had to tighten its monetary policy, it can continue its loose monetary under AIT.”

You can thus see from their example how this provides ample from for over stimulation, particularly so if their inflation targeting time frame is a greater number of years. This creates the very real possibility of a policy mistake, particularly if we do experience an increasingly inflationary future ahead of us.

Implications Of An Inflationary Regime

Inflationary or not, what is almost assured is that we are entering a period of fiscally dominated, MMT style, direct to consumer stimulus. The biggest consequence of this will be the ever rising debt burden of the government. Whether directly monetized by the Federal Reserve or not, how yields react to such measures will perhaps be most telling as to how the coming decades will unfold under an inflationary regime.

Inflation & yields

It is no secret that to many that bonds offer the least risk-reward in the long-term of perhaps any other major asset class in history. “Reward free risk” is how Jim Grant describes investing in the bond market. A period of sustained inflation would be the nail in the coffin for bonds. Such a regime raises several questions. How far can yields rise? How long can such stimulus be sustained before something breaks? Would the government and central bankers want to stop rates rising?

So long as the government intends to continue down its current path of fiscal dominance, which from a political perspective they almost have no alternative, then negative real rates will be their preference. To get an understanding of the how significantly costly it is for the government to finance its deficits, in a recent interview, macro expert Louis-Vincent Gave noted how a 15 basis point increase in funding costs its equivalent to the annual cost of the entire US Navy, whilst a 30 basis point increase is equivalent to the annual cost of the US Marine Corps. As long as the budget deficit continues to expand and is primarily funded on the long end of the curve then rising rates are unsustainable for the government.

Rising rates as a result of inflation would mean the government would either need to issue more debt to finance its existing discretionary spending in the form of social security, defense, Medicare as well as to cover its increased interest costs, or correspondingly reduce spending in these areas. As there is simply no political impetus to be able to cease its discretionary spending, but rather expand this spending, anything other than negative real rates is unlikely to be sustainable.

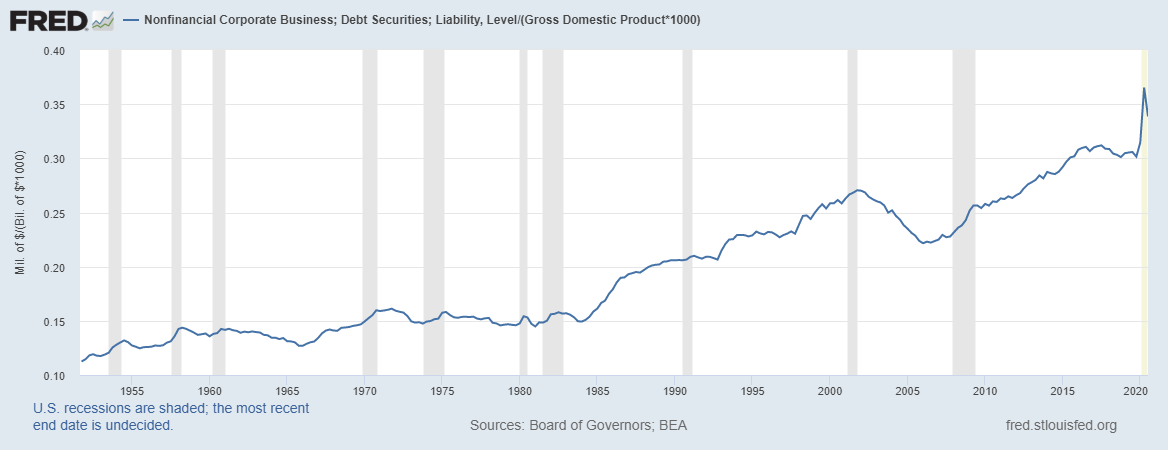

Rising rates are equally as impactful on the private sector too. Corporate debt as a percentage of GDP remains at all time highs.

Source: St. Louis Fed

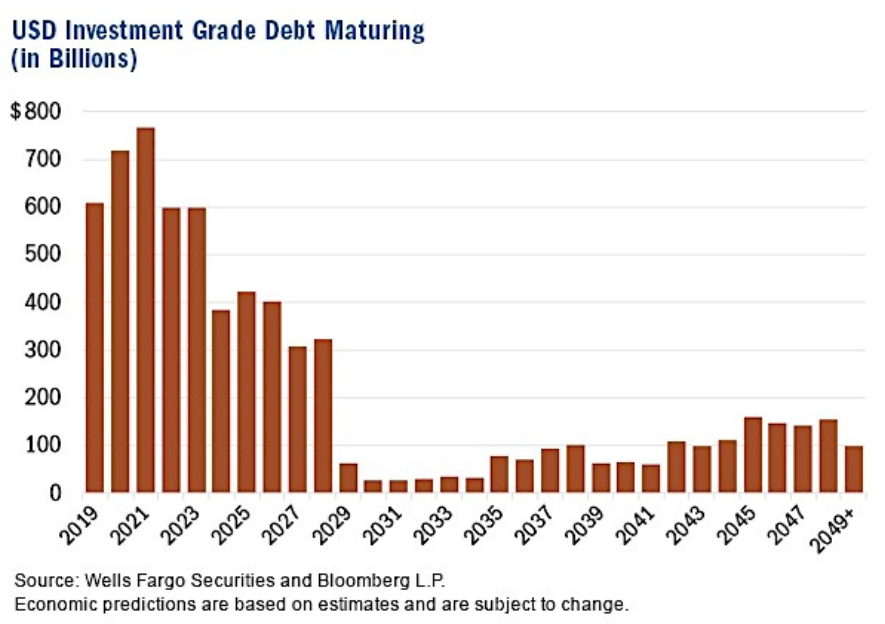

Perhaps more importantly however is how much of this corporate debt is set to mature in the next few years.

Source: Wells Fargo and Bloomberg L.P via FFTT-LLC

With long-term yields continuing to rise and likely to rise much further if an inflationary backdrop occurs, corporations will have no choice but to refinance this debt at higher yields. Corporate profit margins would not bode well in such a scenario.

The country simply cannot sustainably afford a meaningful rise in rates.

If we do get inflation and central bankers do not allow bond markets to function property and price this inflation, then they will at some point need to step in with some form of yield curve control (whether explicit or implicit); we would then have entered an era of financial repression. Financial repression will be indicative of a completely different financial market than that we have experienced over the past 40 to 50 years.

Financial repression

A structurally inflationary environment that is not able to be priced in by the markets due to central bank intervention is not a scenario many alive today have experienced in the developed world. If inflation is allowed to run hot, whilst the government is allowed to continually finance its deficits at capped negative real yields, then this allows the government to essentially inflate away its debt. This is an indirect default on the national debt, and is at the heart of financial repression and yield curve control. The bonds will get paid back, but are paid back in a currency with less purchasing power.

Yield curve control works to remove the markets ability to price long-term yields. The consequences of this must be understood. If inflation is rising without a subsequent rise in interest rates, then the purchasing power of debt will be inflated away without an increase in the purchasing power of consumers. Savings are unable to match inflation and growing prices. Savers are taxed whilst borrowers are bailed out. This would be a complete shift from a free market economy to a planning economy. We would be almost exclusively relying on the growth of the public sector in the place of the private sector.

Furthermore, fiscal dominance and MMT put the onus on the government to then attempt to control inflation. As central bankers are effectively tied to the actions of the government, it will be up to the government officials to act to increase taxes or reduce spending to control inflation. We would see an economic recovery in which central bankers will respond to rising inflation by increasing liquidity by purchasing treasuries to stifle yields, as opposed to withdrawing liquidity. Given how politically incentivized government officials are, for them to be able to reduce spending or increase taxes in any meaningful way would be difficult. Indeed, given the wealth disparity of today, inflationary environments typically favor borrowers at the expense of lenders and have historically resulted in decreased wealth inequality during such times, as I mentioned earlier. Whether financial repression will allow this wealth divide to subside as it has done previously will be telling.

What Does This All Mean For Investors?

At the end of the day, for us investors what really matters is how a structural bout of inflation or stagflation will impact our investing decisions.

Many back-tests will show you what you would largely expect from asset returns during times of inflation; real assets, commodities, energy, value would do very well relative to things like tech, utilities and bonds. Nothing you didn’t know already.

Source: Knowledge Leaders Capital

Source: Incrementum

Whilst this does represents a huge shift from the market darlings over the past 10 years, there are some challenges with these sort of analyses that ought to be addressed. The problem is, much of the investing that is conducted today based on inflation is done so with a significant data availability problem. Though it is likely the best performers during the previous structurally inflationary periods should once again outperform, because we haven’t had true CPI inflation since the early 1980s, we have a limited sample size to compare to. Likewise, back during the highly inflationary 1970s the economy, demographics, global financial system and its interconnectedness were very different to today.

Additionally, given how many of the investing strategies, quantitative algorithms and portfolio construction of today is based on data that only really dates back 30 or 40 years, there is a huge risk in how these strategies will react to a completely different structural market an inflationary regime would bring about.

What is of course a certainty is the death of the bond market. Structural inflation and rising interest rates are undeniably a bonds worst enemies. In regards to equities as a whole, Russell Napier, an avid student on market history believes that equities would indeed perform well up until inflation rates start to reach around 4%, as it is his belief this is the point whereby monetary authorities will start an aggressive attack on inflation by way of raising interest rates. Countries with relatively low debt levels such as emerging markets would also likely do well, given their lower debts allow freedom from the sort of financial repression developed markets are likely to see in such an environment. Likewise, gold and precious metals are undoubtedly a standout asset class in an environment of financial repression and expanding fiscal deficits, as well as inflation.

It is also worth noting how the likely financial repression of an inflationary environment could impact the historically favourable inflationary trades. Value and financials for example not respond well to yield curve control, given that it is the rising rates which generally are a function of inflation that allow the fundamentals of banks and such to improve.

So, Where Are We Now?

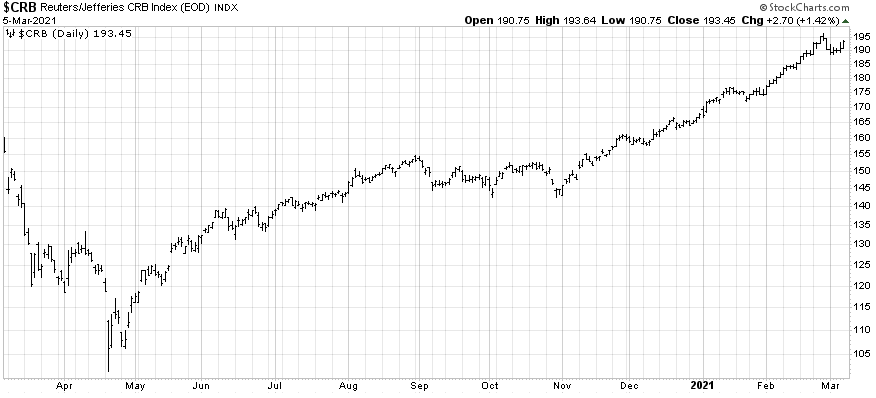

The reflation trade has been hot over the past several months. I wrote about this recently here. Commodities have perhaps been the biggest beneficiary of the inflationary narrative to date.

Source: StockCharts.com

Prices too are rebounding strongly. The ISM manufacturing prices paid index recently reached near 10 year highs.

Source: Investing.com - US ISM Manufacturing Prices Paid Index

Indeed, we are seeing inflationary (or reflationary more accurately) pressures pop up all over the place. Food prices have reached their highest levels since 2014, with such things like meat soaring. It appears only a matter of time before such inflationary pressures start to impact CPI, or perhaps more importantly start to impact the PCE index, which is the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation. The US Empire State Manufacturing Index suggests this is imminent.

Source: Julian Brigden

The same can be said for the Michigan Inflation Expectations survey.

Source: Jesse Felder

It cannot be denied there are immediate reflation pressures present, and as such the recent move up in nominal yields makes sense. However, my concern over these inflationary pressures we are seeing is they more representative of a reflationary economy as opposed to a shift to structurally inflationary environment. Much of what we have seen thus far is arguably a result of supply side inflation, which is very short-term in nature.

If we look at the longer-term inflationary expectations, inflation is not yet much of a concern. The following chart from Hedgopia shows the the spread between the University of Michigan’s inflation expectations for the next year and the next five years. A positive spread indicates inflation expectations for the next 12 months are greater than that of the next five years.

Source: Hedgopia

Likewise, the five-year, five-year forward inflation expectations rate remains well below its average for the past couple of decades, despite a strong pick up since last March. It is not yet signalling any long-term inflationary concerns.

Source: St. Louis Fed

So, in all the inflationary pressures we have seen over recent months should perhaps be more accurately described as reflation. If we are to see a shift to a structurally inflationary environment play out, we would need those longer-term inflationary catalysts I have detailed throughout this article to accelerate in force. Sustained central bank funded fiscal spending (i.e. MMT) and de-globalization to name a few would encourage sustainable demand pull inflation that can increase wages and money velocity, as opposed to the shorter-term supply driven inflation we are witnessing.

There a distinct possibility of a paradigm shift to a structurally inflationary future and only time will tell if that is the path ahead of us. But, for now we are more likely to see cyclical bouts of inflation/reflation. This type of environment would still create uncertainty. If it is one thing investors don’t like, it’s uncertainty.