Peak Inflation Is Upon Us

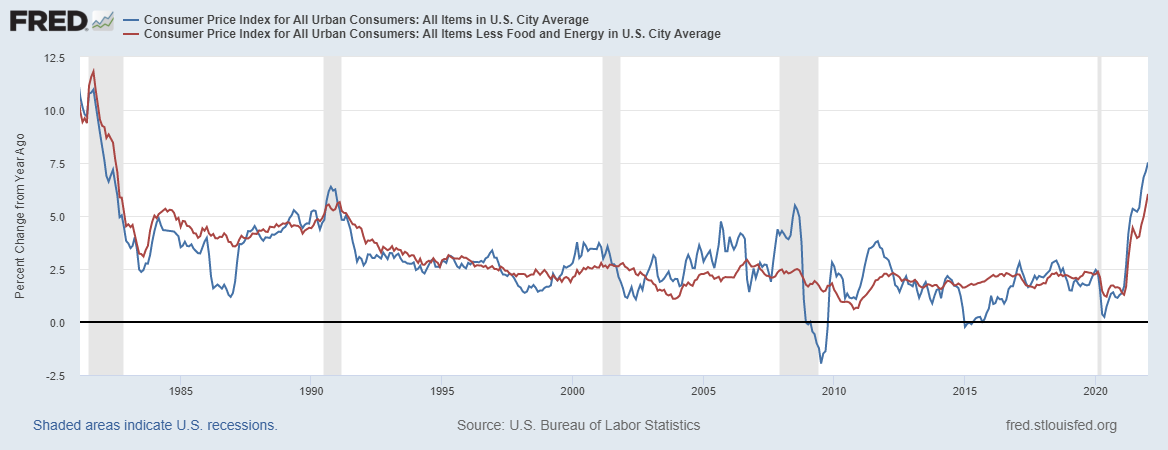

With January’s 7.5% headline CPI reading coming in as the highest inflation number in nearly 40 years, now seems an opportune time to assess the outlook for inflation and try to gauge whether this is a trend set to continue or if peak inflation is upon us for this cycle. One way or another, the implications for financial markets and the economy are immense.

At the beginning of 2021, I wrote a comprehensive article discussing the catalysts of why we could experience a move in inflation unlike anything seen in decades. As I mused upon in this piece, through a combination of fiscal spending, a release of lockdown driven pent-up demand, an almost instantaneous shift in favour of goods spending over services spending as consumers worldwide were forced inside, accompanied by crippled supply chains, a tight labour market as so many individuals “retired” and a multitude of other factors, we have indeed seen both headline, core and median inflation readings reach their highest levels since the 1980s.

Understanding where inflation is heading is not only important from an economic perspective, but the directional moves in the growth rate of inflation play an important role in the outright performance of financial markets. When both inflation and economic growth decelerate in tandem, the implications for asset prices have not been favourable in the past.

Furthermore, inflation feeds into consumer sentiment and impacts demand and thus economic growth, and perhaps most importantly, given stable prices are one of the Federal Reserve’s dual mandates, the direction of growth in inflation and average level of inflation are some of the most important variables used by the Fed in setting monetary policy.

Unsurprisingly, the consequences of these price increases are starting to be felt throughout the economy to the point that inflation is sowing the seeds of its own demise. When you raise prices on consumers faster than you raise wages, real incomes become negative and you destroy demand and thus consumption. That is exactly what is occurring.

Couple this with the fact that inflation running this hot (a political nightmare) is forcing the Fed to become incrementally hawkish and bring-forward the tapering of monetary conditions. They have no choice but to respond by raising rates and reducing their balance sheet, that is, raising borrowing costs and reducing liquidity for already constrained business’ and consumers. With inflation as the culprit, we have a myriad of factors set to hold down economic growth and impact financial markets, and ultimately, will become a headwind for inflation itself.

So where is inflation heading in 2022?

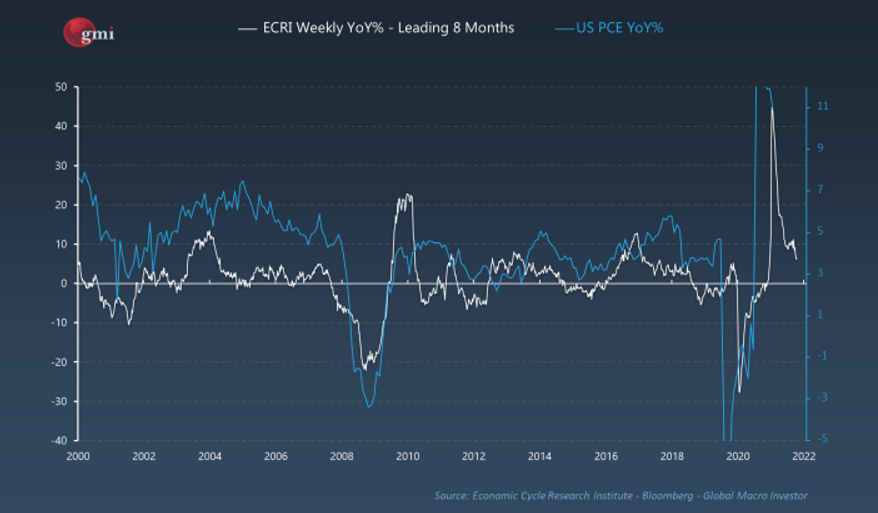

As we look into some of the leading indicators of inflation, we can see how these headwinds in economic growth will thus transpose themselves into headwinds for the growth rate in inflation. The business cycle is one of the primary leads of the inflation cycle.

As increasing prices continue to destroy demand, my outlook for economic growth for 2022 is one of deceleration. This will begin to effect CPI and PCE numbers as the growth cycle will likely begin to decelerate more meaningfully in the second and third quarters of 2022.

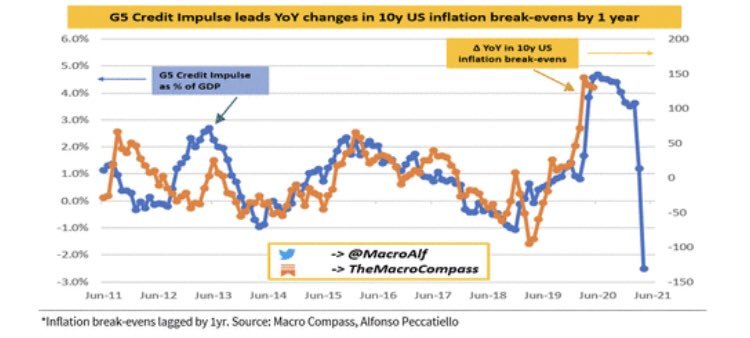

Another way of illustrating this dynamic is by looking at how the G5 credit impulse leads inflation breakevens by around 12 months.

Source: Alfonso Peccatiella

The credit impulse metric measures the rate of change of newly created credit via commercial bank lending and government stimulus and is one of the better long-term leading indicators of the growth cycle, and by extension the inflation cycle.

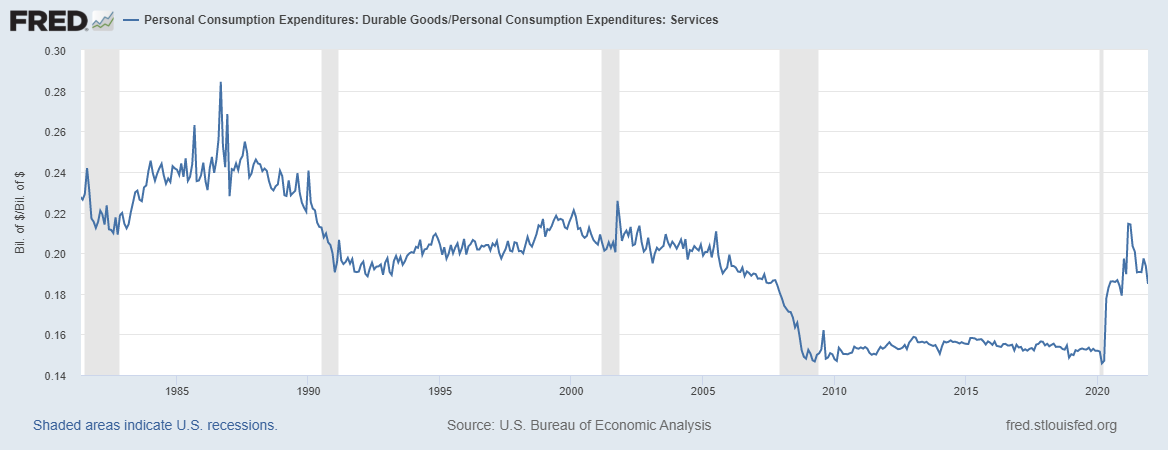

With slowing growth and demand, we should expect to see a normalisation in goods vs. services consumption. One of the biggest drivers of this inflation cycle was the sudden change in consumer spending habits from that in favour of services over goods to goods over services, a radical shift induced by the worldwide lockdown mandates at the onset of the pandemic.

As consumers stayed at home and their bank accounts flooded with stimulus cheques, we saw a radical shift of spending in favour of goods over services, resulting in a sudden increase in demand for durable goods and thus requiring a need for raw materials to produce said goods during a time where supply chains were virtually non-existent. Given how much we have relied on foreign suppliers for the supply of most goods due to globalisation, this lead to a squeeze on raw materials and their prices which has been incredibly inflationary.

We are however starting to see spending trends normalise as the ratio of goods vs. services consumption seems to have peaked back in April 2021, as illustrated in the chart above.

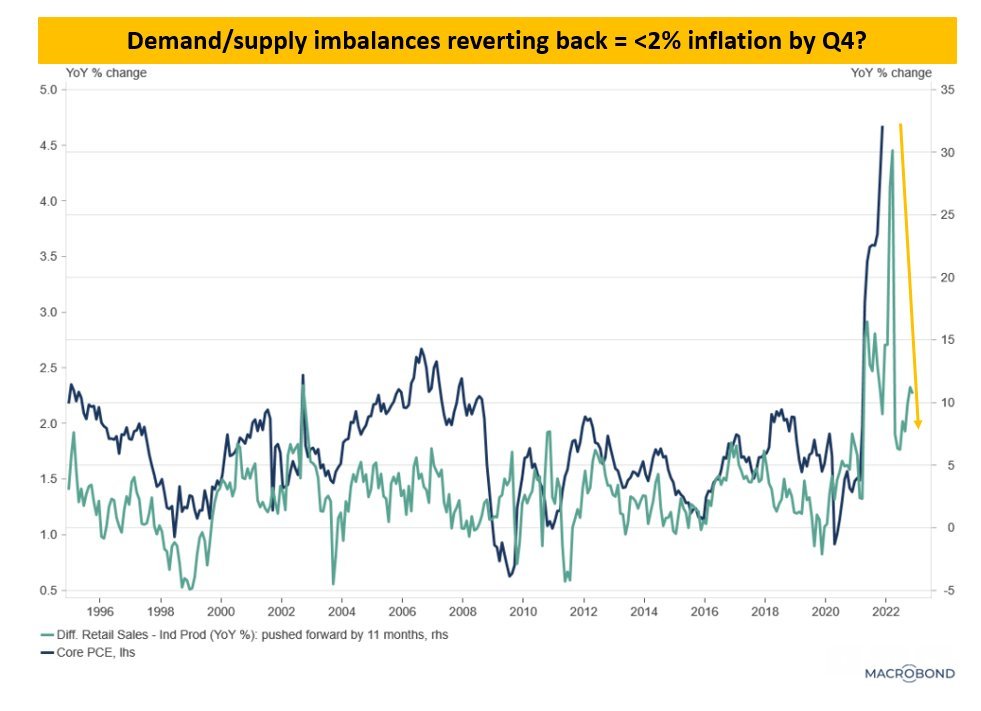

This dynamic is likely to lead inflation lower over the next 12 months, as proxied by the difference in the growth rate of retail sales (demand) and industrial production (supply).

Source: Macrobond via Alfonso Peccatiella

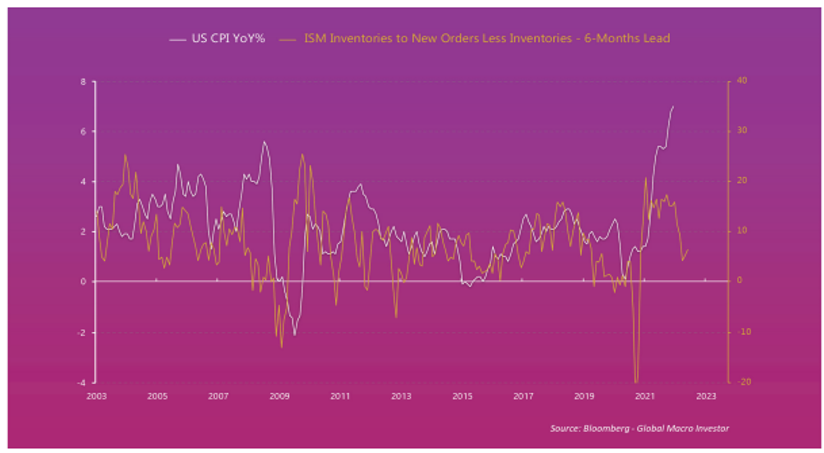

Just as the radical shift in spending towards goods (that were undersupplied) relative to services was inflationary, the shift back towards consumption patterns in favour of services relative to goods (which are now oversupplied) is likely to now be disinflationary. The spread between the ISM Manufacturing Survey New Order and Inventory is too foretelling this message.

Source: Global Macro Investor

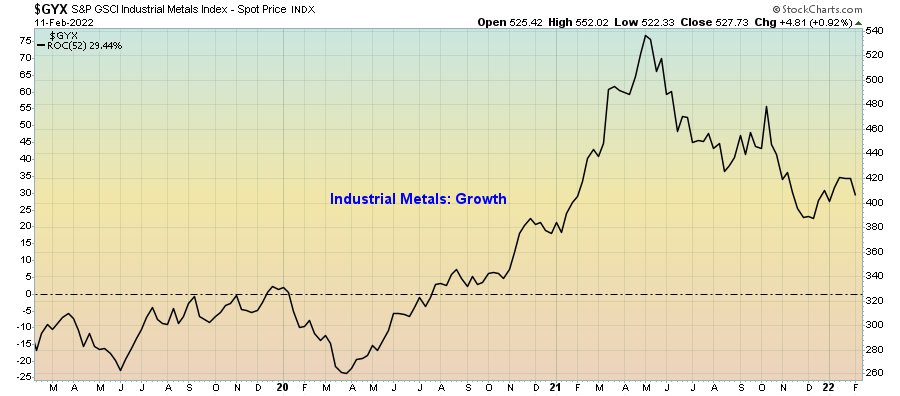

As these dynamics saw the growth rate of industrial metals skyrocket throughout the second half of 2020 and early parts of 2021, the direction in the growth has largely been moving down since Q2 2021. The movements in industrial metals are a good indicator of demand and supply imbalances as their prices are very sensitive to the manufacturing process.

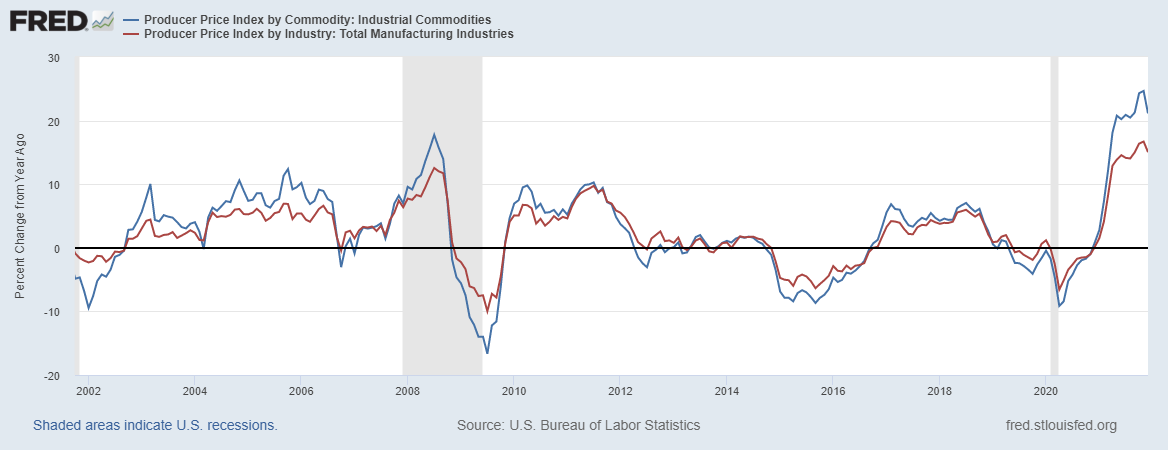

The growth rate in the Producer Price Index for industrial commodities and manufacturing both look to be peaking which would seemingly be a result of the dynamics I have highlighted above.

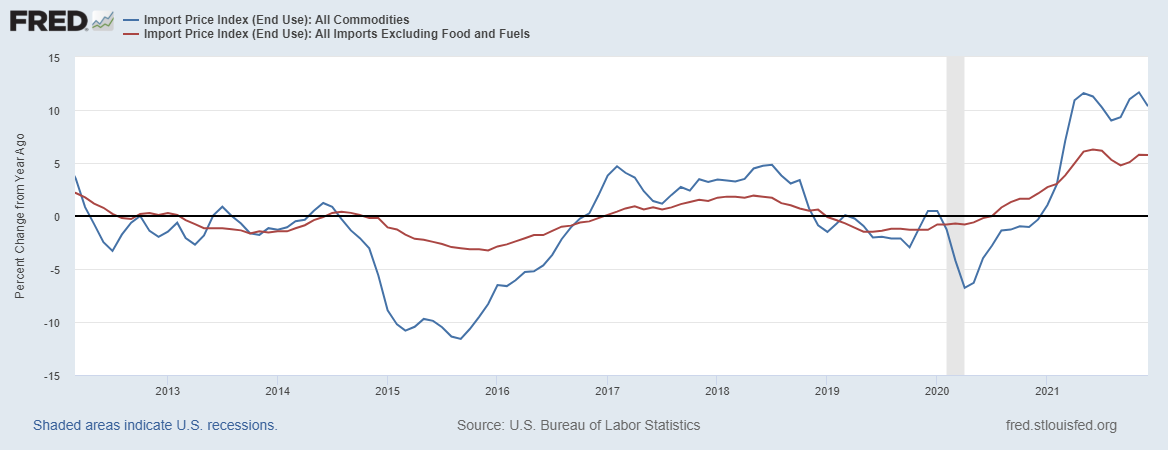

Import prices for commodities too appear to have stagnated.

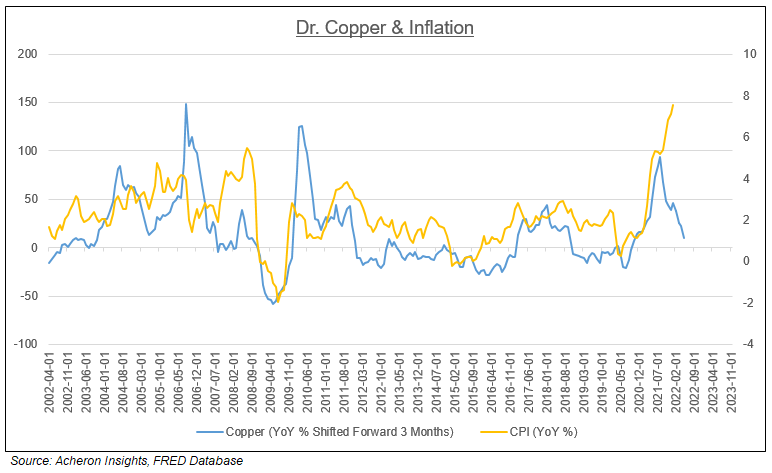

Likewise, Dr. Copper, who was previously signalling inflation, is now calling for disinflation.

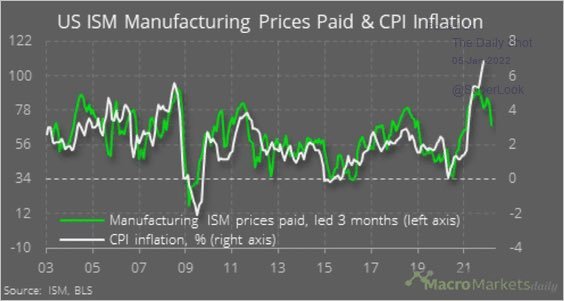

So too is the ISM Prices Paid index, another of the more reliable leading indicators of inflation.

Source: Macro Markets Daily via Rob Hager

Not only is slowing growth and normalising consumption patterns headwinds for the continued acceleration in inflation, but easing supply chain pressures should begin to flow through to the CPI data as 2022 progresses.

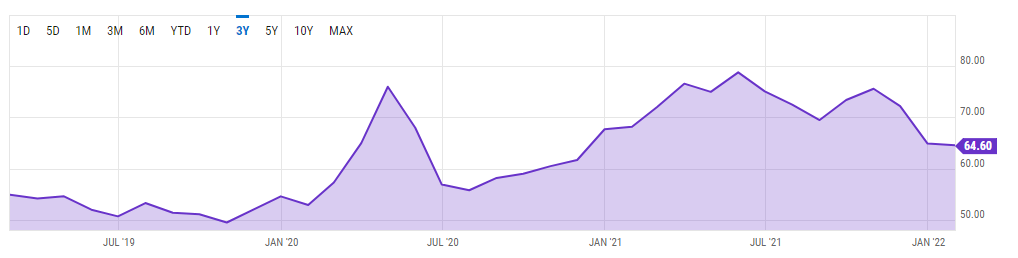

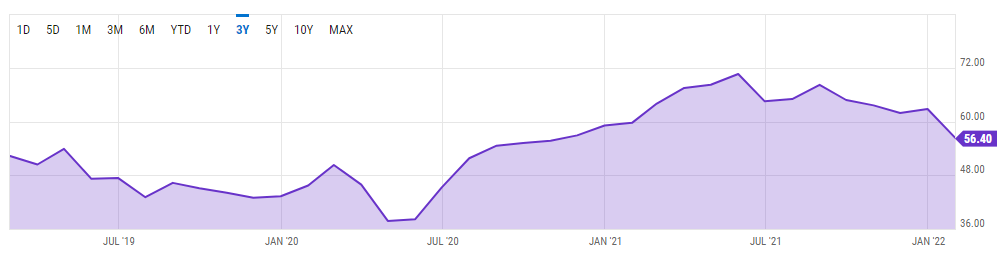

Firstly, the ISM Manufacturing Supplier Delivery Times index has slowly been trending downward after peaking in mid-2022.

ISM Manufacturing Supplier Deliveries Index

Source: YCharts

A rising number in this index is representative on an increasing number of manufacturing businesses reporting increased delivery times, indicative of high consumer demand and can leads to backlogs, supply chain constraints and thus pressure prices upward. Should this number continue lower as it has done in recent months, we should see some relief for order backlogs and a further easing of supply chains.

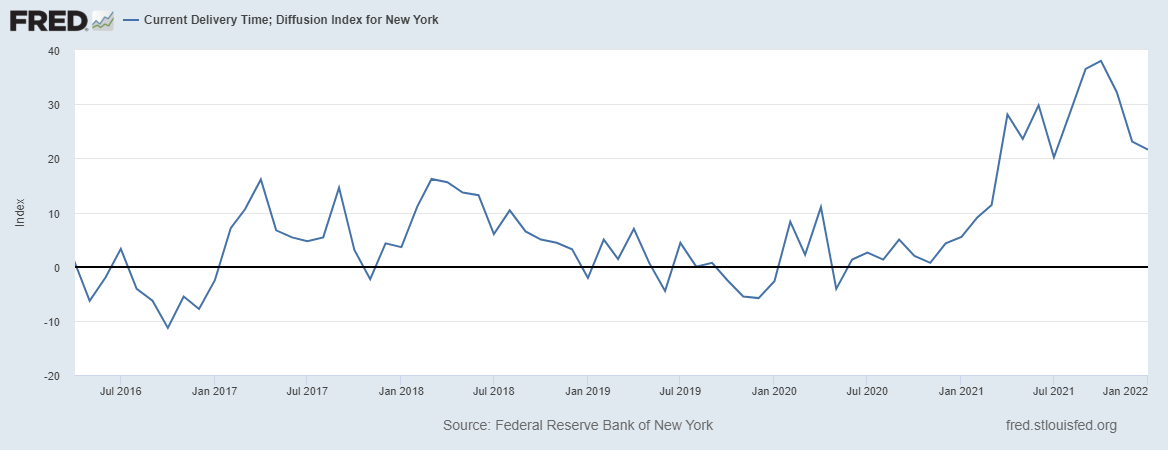

Also confirming this message is the New York Federal Reserve’s Empire State Manufacturing Survey Delivery Times index, which too has decelerated meaningfully over recent months.

So too the ISM Manufacturing Backlog index, which looks to have peaked in mid-2021.

ISM Manufacturing Backlog Index

Source: YCharts

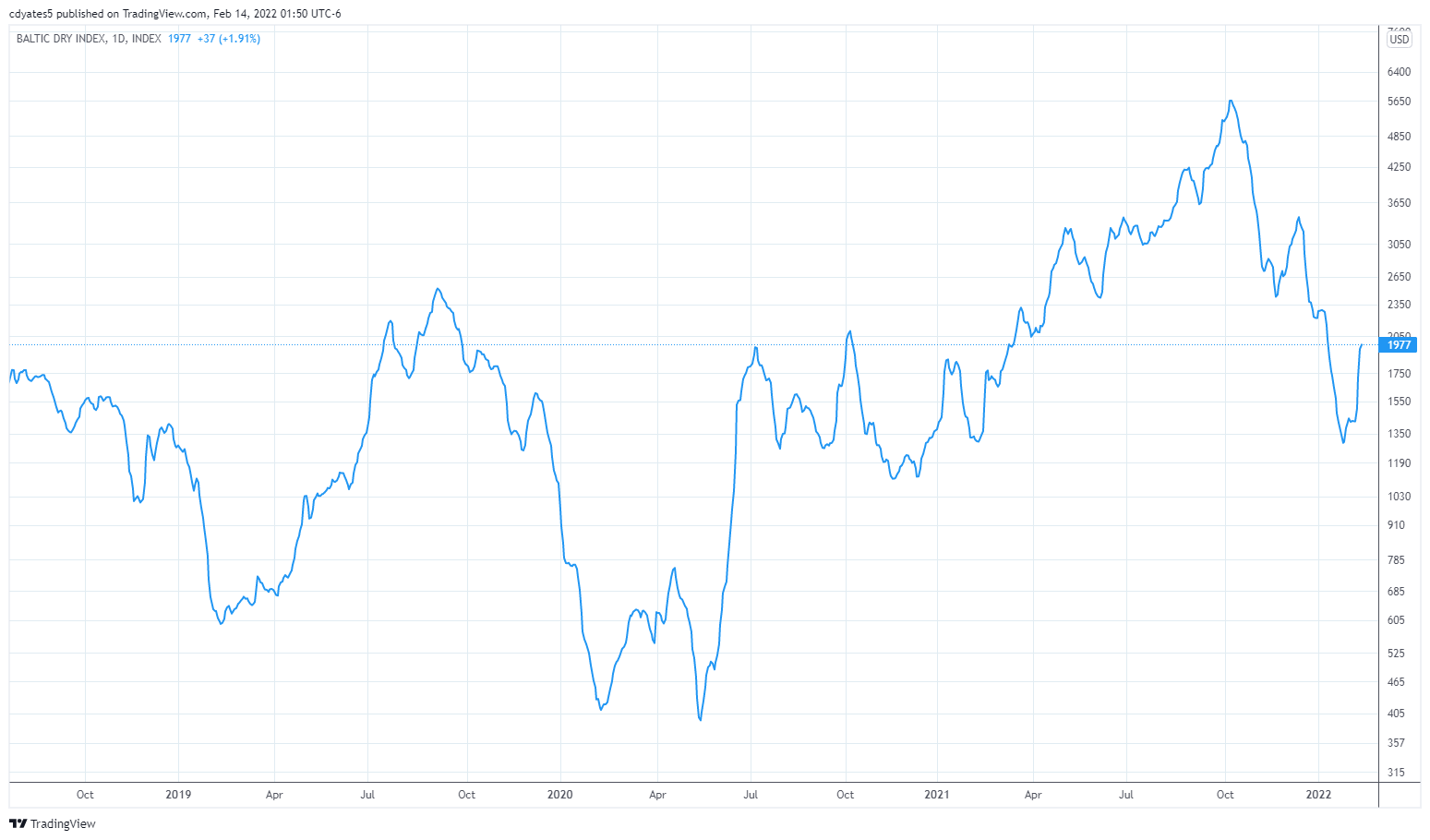

If we look to the Baltic Dry Index, which measures the cost to ship bulk commodities and provides another good proxy for supply chain constraints, we can see how much the index has cooled off since October.

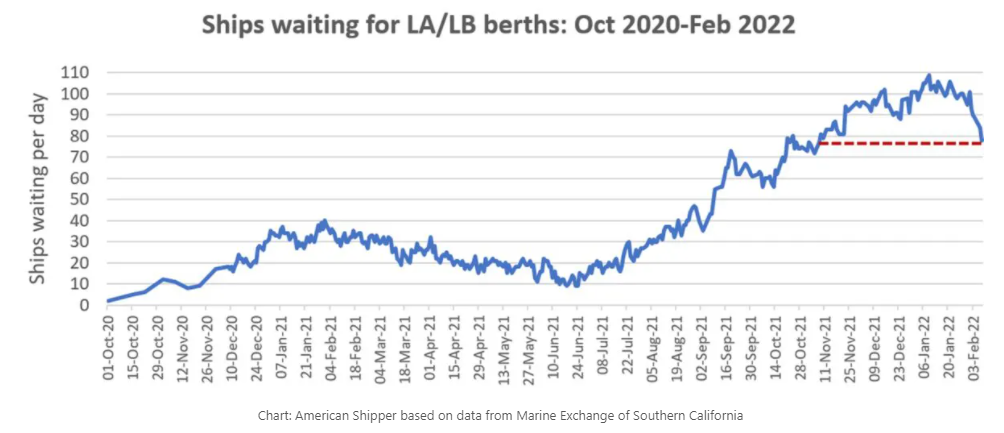

Couple this week the fact that port congestion looks to potentially sorting itself out.

Source: FreightWaves

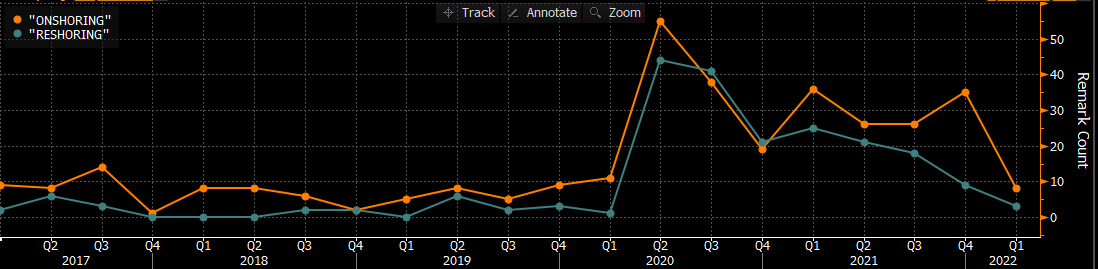

And finally, mentions of “on-shoring” or “off-shoring” as proxies for supply chain discussions within corporate earnings calls have similarly cooled off of late, again suggesting we are beginning to see an easing of supply chain constraints.

Source: Fernando Vidal

As we can see, there is an increasing amount of evidence to suggest we are beginning to see signs that peak inflation from a rate-of-change basis is nearing and the probabilities are increasing that we see a material deceleration of inflation come the second half of this year. The slow easing of supply chain pressures, slowing economic growth and waning consumer demand, and most importantly, quite unfavourable base-effects for YoY growth rates, all ought to provide significant headwinds for any continued acceleration in the growth rate of inflation.

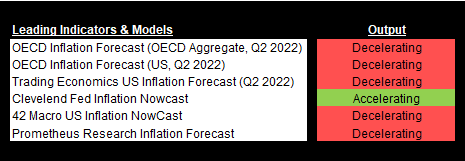

Unsurprisingly, a number of econometric forecasters of inflation I monitor are pointing towards a deceleration throughout 2022, particularly in the latter half, as we can see below.

However, it must of course be said there remain a number of cyclical tailwinds for inflation that could see the growth rate continue higher in February, March and even April’s CPI readings. That is in fact exactly what the Cleveland Fed’s inflation NowCast model is predicting for the month of February.

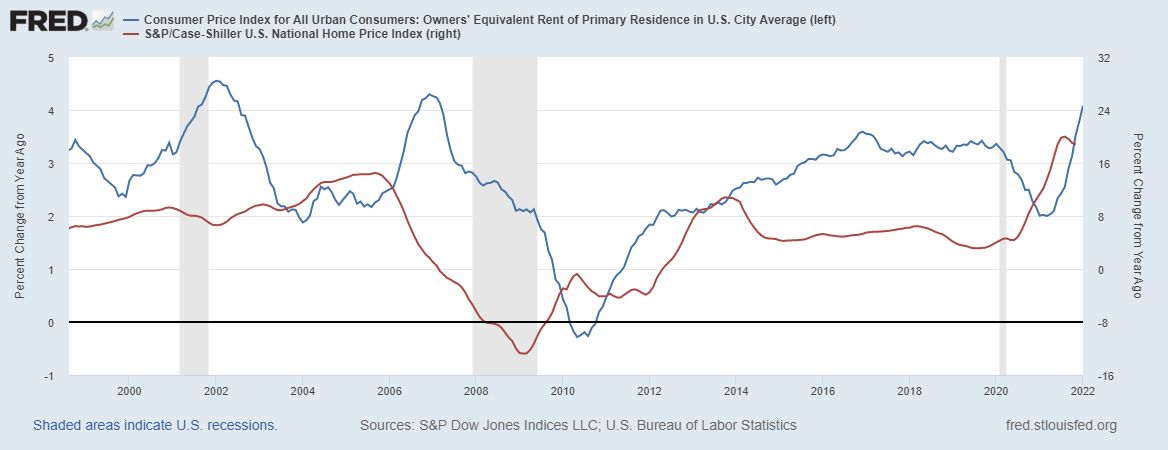

The culprit? Well, Owners Equivalent Rent (OER) for one represents roughly 25% of the CPI basket and is likely to be a tailwind for CPI for some months still given home prices lead OER by about 12-18 months. Although home prices look to be stabilising, the relief this will provide for OER will not likely be felt until Q2. OER has been one primary reasons why inflation has continued to accelerate of late.

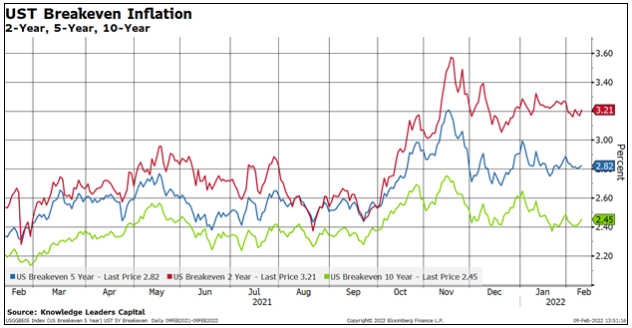

Indeed, the second half of 2022 looks to be the time whereby inflation starts to decelerate meaningfully to the downside. From the perspective of market expectations, as noted by Knowledge Leaders Capital recently, the US Treasury market seems to have priced in peak inflation back in November.

Source: Knowledge Leaders Capital

Even by examining the precious metals markets we can ascertain a similar conclusion. Doesn’t the fact that gold and silver prices, so often referred to as the ‘ultimate inflation hedge’, have gone nowhere tell us that the smart money still does not view inflation as a long term concern?

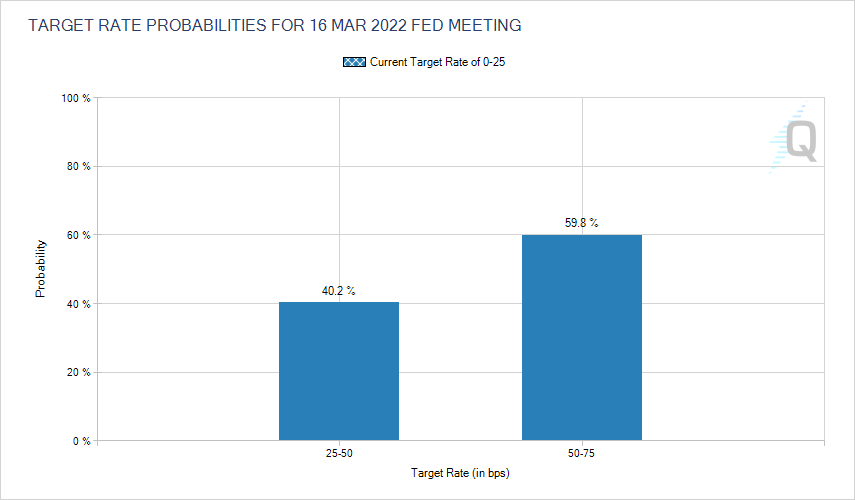

So, should inflation indeed decelerate meaningfully throughout the second half of 2022, this opens the door to a potential policy mistake by the Fed. Following the release of January’s surprise CPI number to the upside, the market is now pricing in a 40% chance of an increase in the Fed Funds rate to 25-50 bps and a 60% change on an increase to 50-75 bps in March.

Source: CME Group

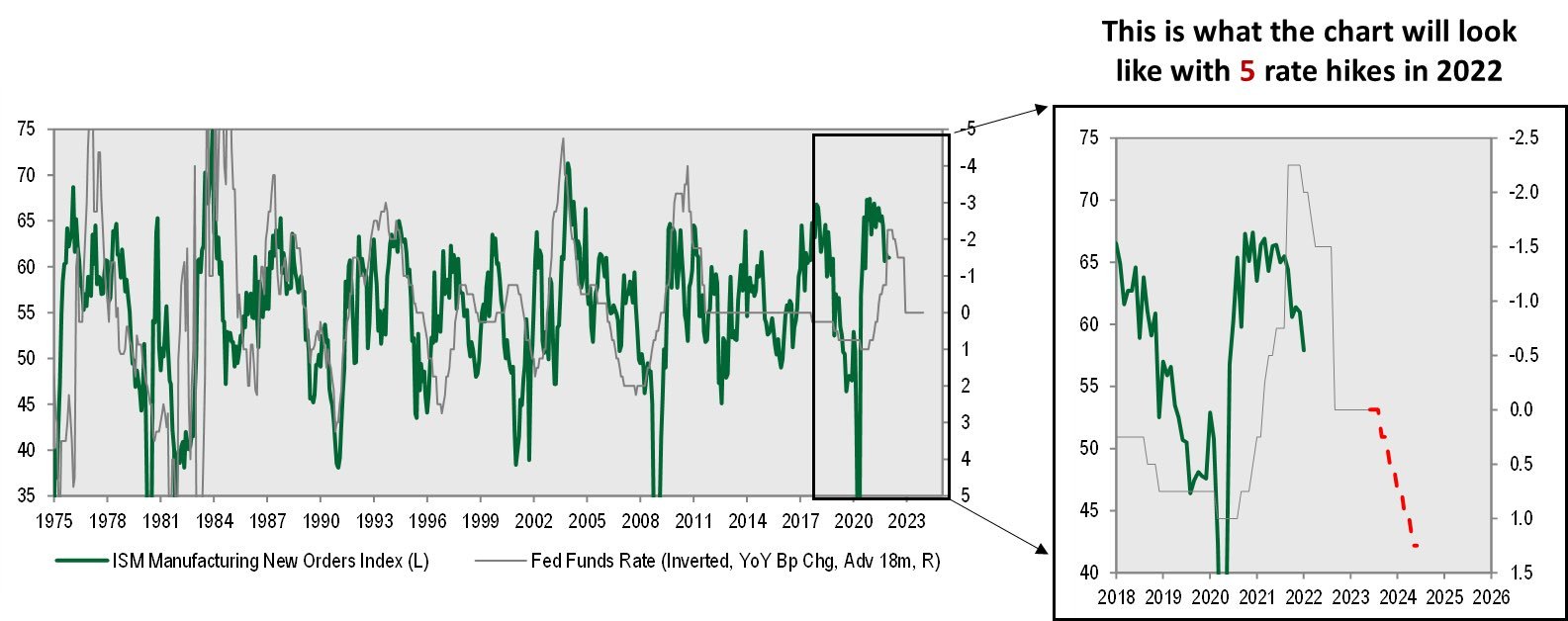

Either inflation decelerates and the Fed is limited by the number of rate hikes they can successfully implement over the coming months, or a material slowdown in growth and potentially a recession appears a genuine possibility in late 2022 and early 2023 as the Fed is forced to hike into an inflation spiral and a growth slowdown.

Source: Michael Kantrowitz, CFA

The great fallacy here lies in the notion that raising interest rates will somehow quell inflation. The Fed’s response to higher prices is to tighten financial conditions and raise borrowing costs in the hope this will help consumers and lower prices. The Fed of course have no choice in the matter as it is part of their mandate to achieve stable prices, and all they can do is use the tools available to them to attempt to achieve this.

Clearly, the Fed is backed into a corner. A stagflationary outcome will ultimately force the Fed to tighten into a slowdown, which will further exacerbate that slowdown. As this would likely crash the stockmarket, depending on where the ‘Fed Put’ now resides, we may well see a policy reversal whereby the Fed loosens into an inflation spike. Given where the Federal debt and deficit position currently stands for the United States, it appears a policy reversal to be the higher probability outcome later in 2022.

This outcome appears increasingly likely should we indeed see a deceleration in inflation later in 2022. If history is any guide, the market pricing of rate hikes has been almost always too ambitious.

Source: Roberto Perli

This would perhaps be positive for asset prices as a backing off from monetary tightening would provide some relief to the material impact on asset prices the current tightening schedule of the Fed would portend.

Though inflation is likely nearing its peak, a higher average inflation rate does have ongoing implications for monetary policy, and will continue to restricts the Fed's ability to step in and assist asset markets given their mandate is to maintain price levels and not asset markets. In all likelihood, the Fed will (finally) choose to help Main Street over Wall Street (unsuccessful as this may be, for political and creditability reasons, they have no choice). In effect, the Fed put will be determined by the level of inflation.

There do remain cyclical tailwinds for inflation in place for the foreseeable future to such an extend that we will likely see a much high average rate of inflation than we are used to in recent times. A politically driven structural shift to fiscal dominance, commodity bull market, potentially for accelerated de-globalistion and Black Swan events such as the Russia-Ukraine crisis that could see energy and food prices skyrocket are some such examples.

However, the long-term structural forces of disinflation and are only going to accelerate going forward and will continue to ultimately drag down inflation over the coming years, such is the gravity pull that they are in debt, demographics and technology.

Key takeaways

Following the release of January’s near 40-year high CPI reading, the evidence is increasingly pointing to peak inflation for this cycle.

Base effects, slowing growth, normalising spending habits and improving supply chains will work against the growth rate of inflation as 2022 progresses.

This has significant policy impacts, as the Fed is basing their tightening decisions on lagging data, and as such, are set to significantly tighten monetary conditions into a growth slowdown.

Though the Fed’s actions may end up being a policy mistake should they over-tighten, for credibility and political purposes, they have no choice.

Should we see growth and inflation decelerate meaningfully in 2022, don’t be surprised to see further monetary easing come 2023.