The Importance of the Labour Market

Summary & Key Takeaways

The Fed’s mandate is for stable prices and maximum employment. By understanding the trends within the labour market, we can gain valuable insight into the likely monetary policy actions of the Fed.

With an undersupply of workers and cycle low in unemployment, the labour market is signaling tight monetary policy should continue for now.

However, unemployment and wages are lagging economic indicators. The leading indicators of both wages and employment suggest a relief in wage growth and rise in unemployment are on the cards for later this year, and thus, the signs are there for a potential dovish policy pivot by the turn of the year.

Any dovish pivot would likely be too late given the dire outlook for the economy in the near term, resulting in a policy error by the Fed as their reaction function is once again based on lagging data not representative of the current state of the economy.

Why analyse the labour market?

From an economic and growth cycle perspective, both employment and wage data are lagging indicators. However, given the Fed's mandate of full employment and stable prices, their policy reaction function is heavily influence by what is occurring in the labour market. This is the case in terms of both employment levels and wage growth.

By understanding where these trends may be headed, we are able to ascertain what the Fed's future policy stance is likely to be.

Where does the labour market stand at present?

With an undersupply of workers, rising wages and low unemployment, the labour market at present is one of extreme tightness. Such information should be of no surprise to anyone as we have all likely been impacted one way or another by the staff shortages gripping most developed nations.

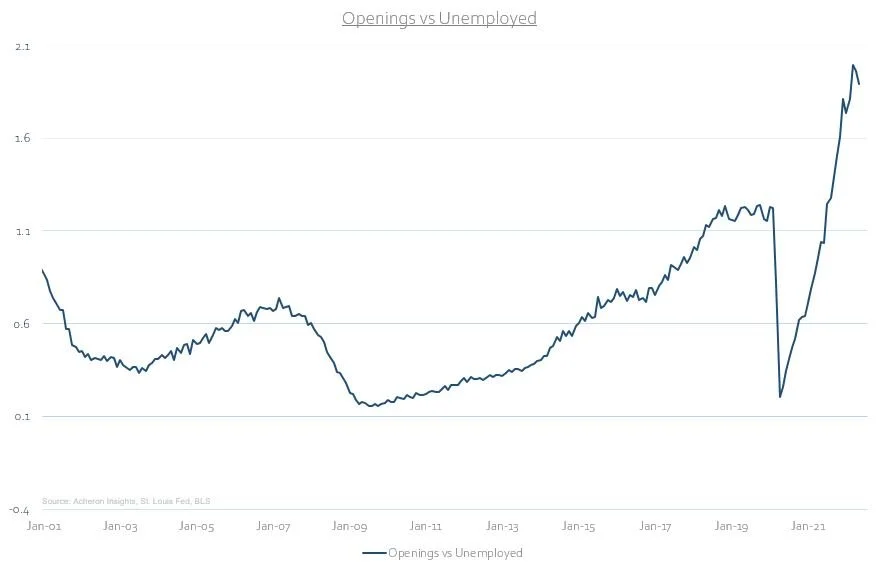

In measuring this tightness via the ratio of the number of job openings within the US relative to the number of unemployment persons, when the total number of openings exceeds those who are unemployment yet part of the labour force, this is indicative of a tight labour market and increasing wage pressures. As it stands there are roughly two openings for every job seeker, nearly double the previous cycle high and materially higher than anything seen in decades.

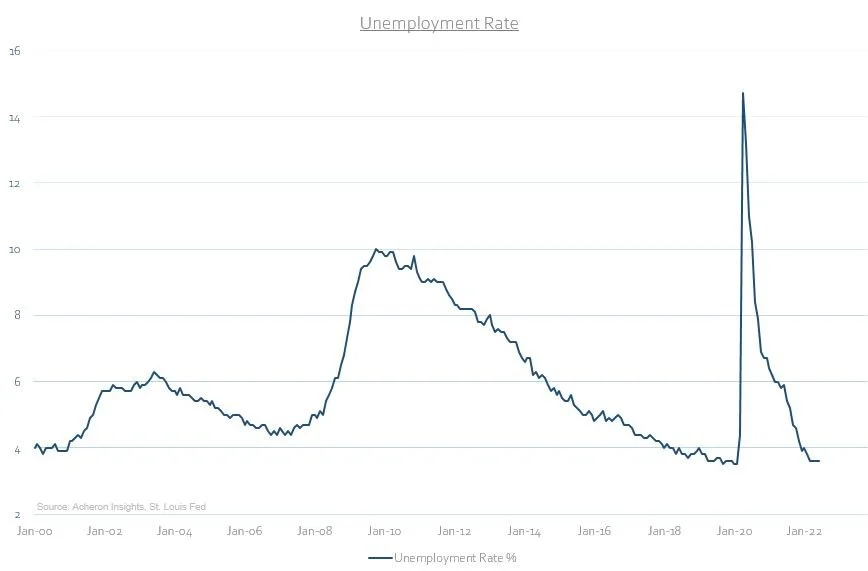

Likewise, we have an unemployment rate sitting at its cycle lows and on par with that of recent cycles.

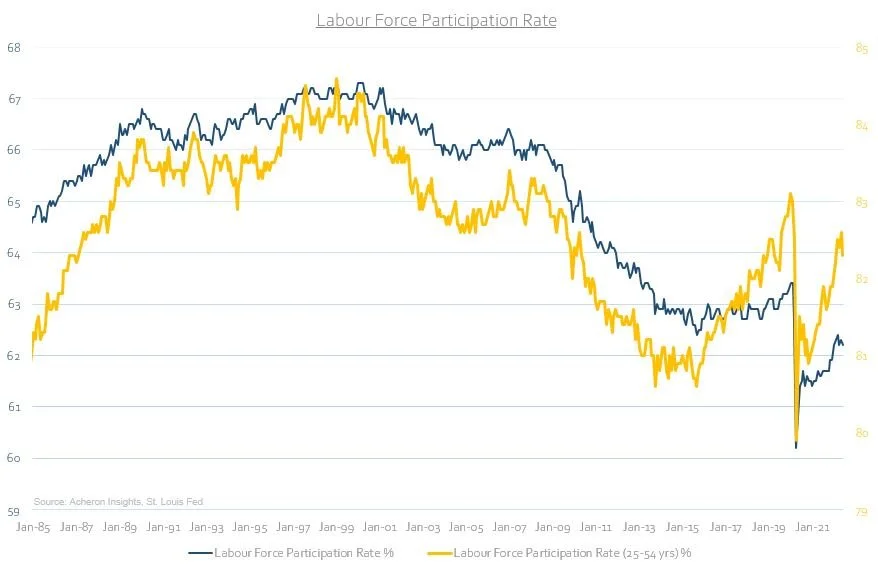

Reaching such levels of low unemployment is made easier when the labour force participation rate is well below its previous cycle highs, notably so for the most economically important 25-54 year old demographic.

Therefore, it should be unsurprising to see how such developments have seen wages on both a growth rate and absolute basis soar.

Coupling significant wage growth with low unemployment gives the Fed a recipe for hawkish monetary policy, thus explaining much of the Fed’s policy actions of late. Indeed, whilst having an understanding of current picture of the labour market allows us insight into the current monetary policy actions of the Fed, having an understanding of the future direction of the labour market allows as to more accurately predict the future monetary policy decisions of Powell & Co.

Will the labour market continue to signal to the Fed for hawkish monetary policy, or are we undergoing a shift in the labour market dynamics yet to show up in the hard data? When will the labour market allow the Fed to pivot? It is these questions whose answers are of true value to investors. Let’s see what’s in store for both unemployment and wages.

Leading indicators of employment

There are a number of leading indicators that provide great insight to the likely direction of employment, and thus the potential direction of monetary policy.

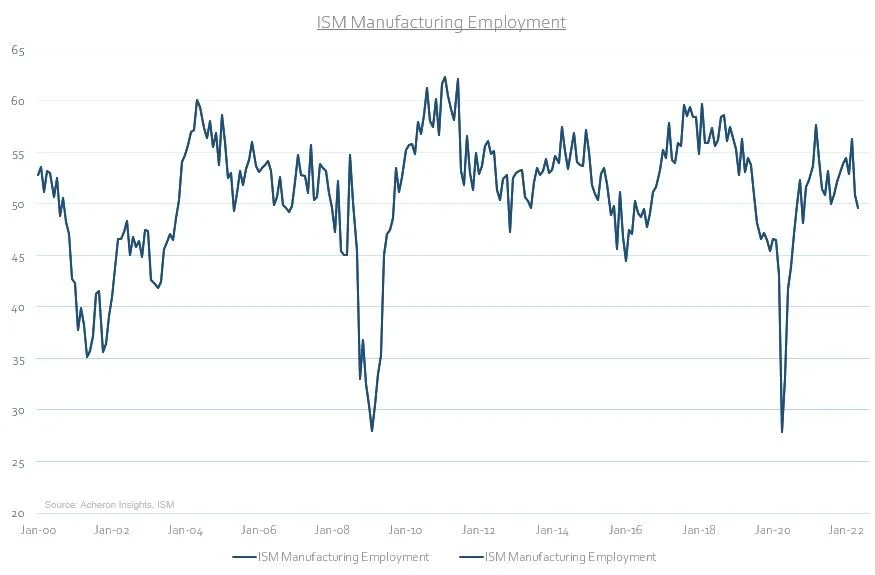

Firstly, it is important to take note of the employment trends within the manufacturing sector in particular given the cyclical nature of manufacturing and its importance as a key driver of the growth cycle. If the economy is slowing and we are amidst a growth cycle downturn and potential recession, in almost all cases the unemployment rate will rise, and in most cases we should see this show up first within manufacturing related employment. To examine such trends in a leading fashion, the Manufacturing Employment component of the ISM Manufacturing Survey is perhaps the most timely indicator of manufacturing employment. Notably, the latest release saw its first sub-50 reading since the recovery. A reading below 50 implies the majority of firms surveyed are planning to reduce their level of staff.

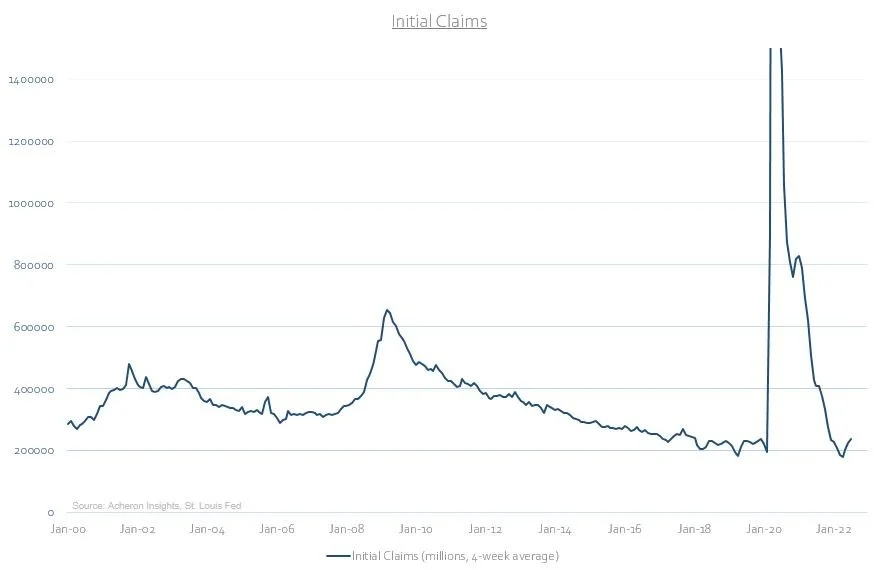

On a broader basis, initial claims for unemployment benefits has seen its largest increase since the early 2020 lockdowns. Initials claims is another excellent lead on the overall level of unemployment.

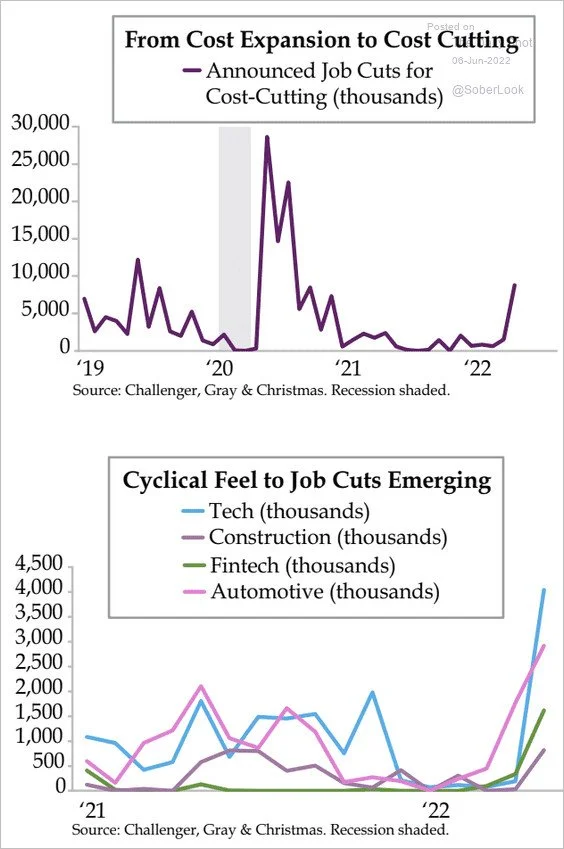

More notably however are the number of layoffs we are witnessing in the tech sector this year.

Source: The Daily Shot (@SoberLook)

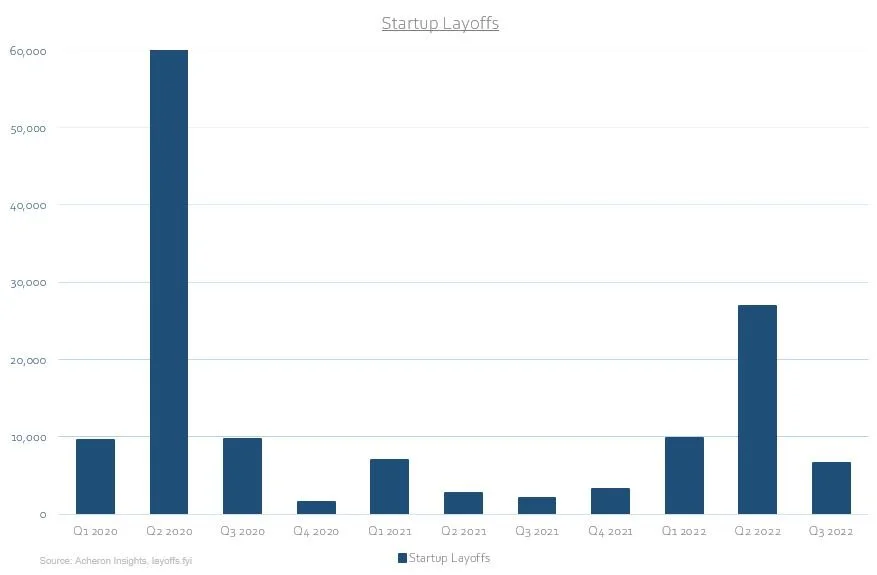

As well as start-ups. It seems inevitable these trends will seethe through to the broader economy.

Remember, tech related equities have been hit the hardest relative to most other sectors of the stock market during the recent sell-off. As rates have risen, capital has dried up and corporate earnings have begun trending lower resulting in a clear upward trend in layoffs and layoff announcements. Indeed, when a company like Apple signals it is slowing hiring, it is only a matter of time before these trends show up in the overall data.

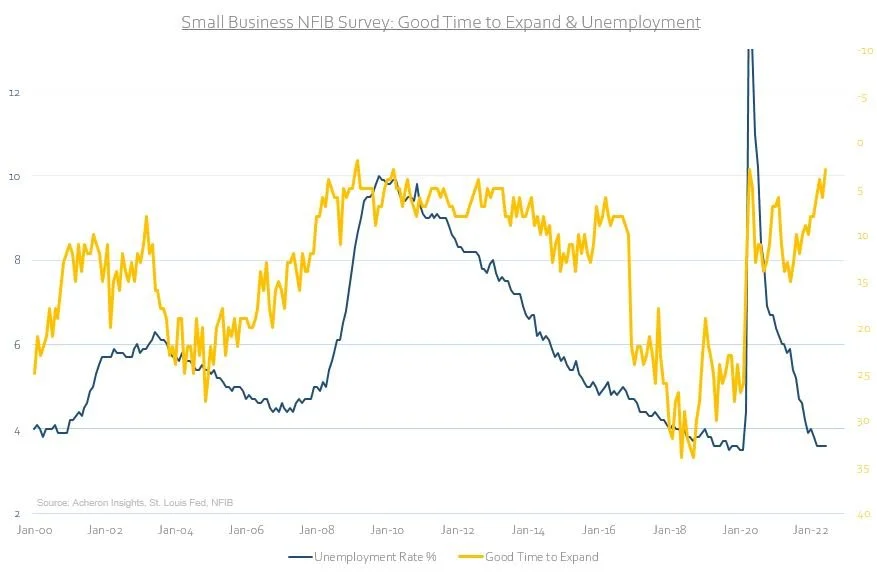

Small businesses are too feeling the brunt of this slowdown. According to the US Small Business Administration, small businesses account for approximately 66% of all new jobs and roughly 44% of total US economic activity. Thus, it is important to play close attention to what is taking place within the small business landscape as their implications for the economy are profound.

We can see the latest NFIB small business survey data is showing the number of small businesses who are willing to expand is nearing decade lows (inverted below), an outcome which generally precedes rising unemployment.

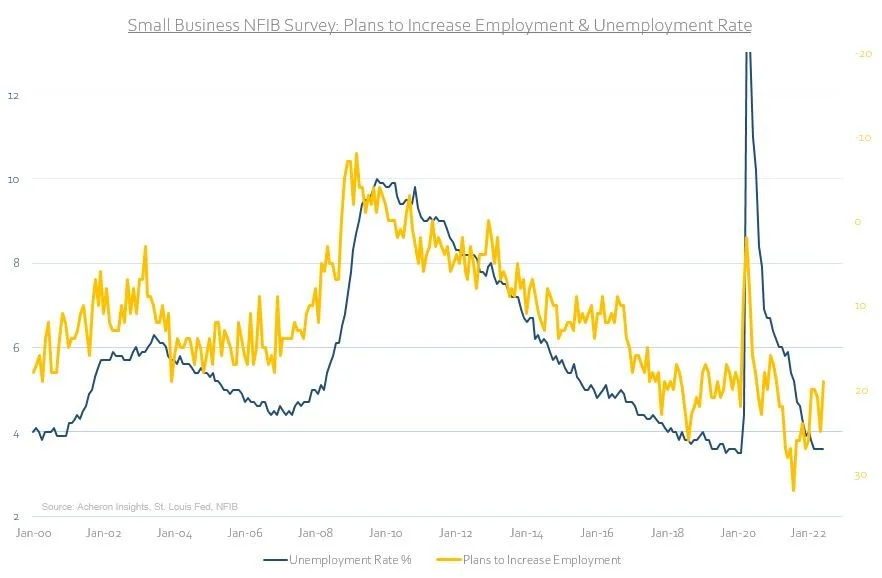

Likewise, the number of small businesses planning to increase employment is also ticking lower. In the past, similar trends have also preceded significant rises in unemployment.

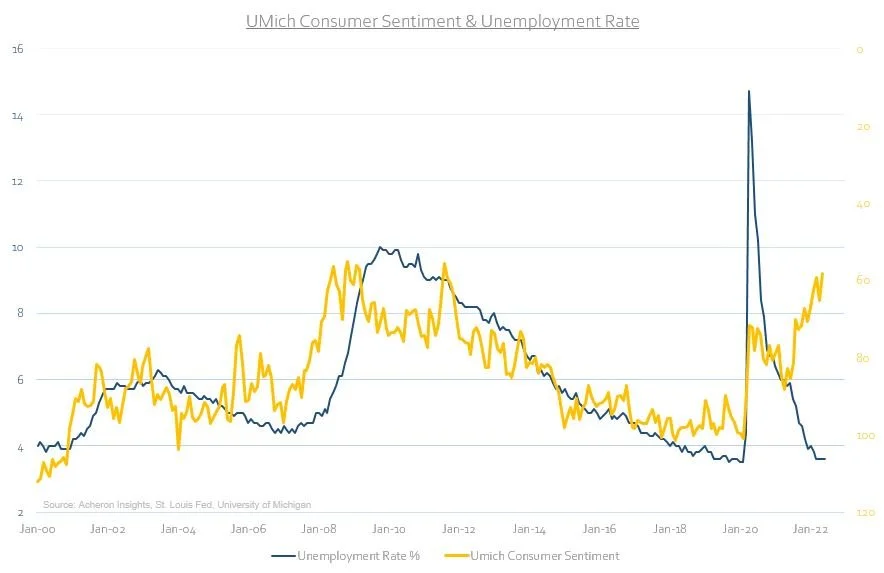

Unsurprisingly, as layoffs creep higher and the small business outlook deteriorates, consumer sentiment is dropping like a stone. The implications of inflation, negative real income growth and the poor economic outlook on consumers are clear. Indeed, we can see how the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment survey has historically lead unemployment by around 6-12 months, with there now a significant divergence between the two.

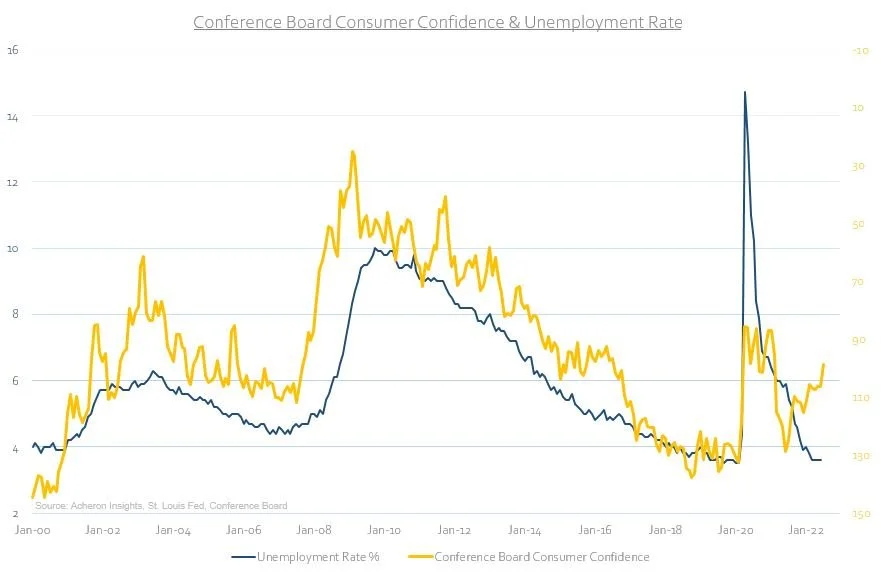

The Conference Board Consumer Confidence index is also signaling that rising unemployment is forthcoming.

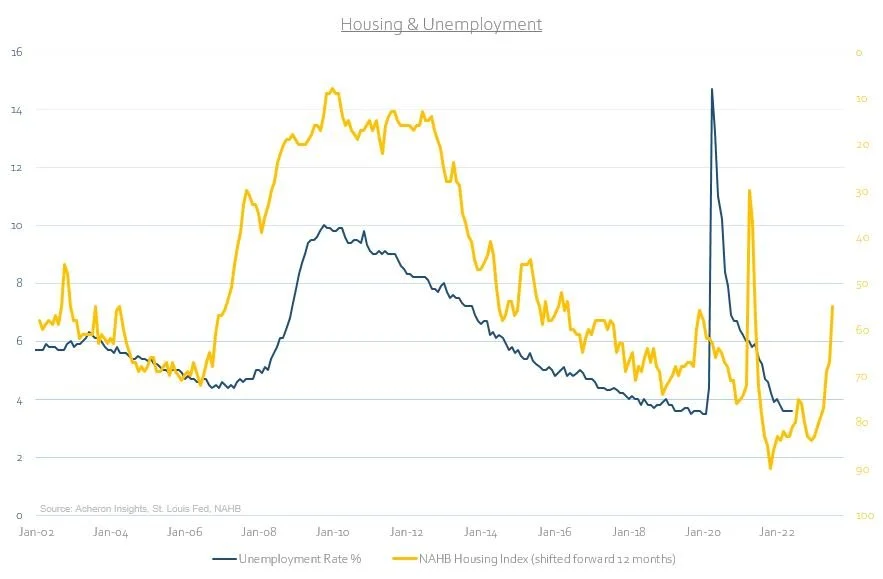

Just as important to economic activity as small businesses is the housing market. According to the National Association of Homebuilders, housing investment, construction and housing related consumption contribute to around 15-18% of GDP. With a cyclical slowdown in the housing market well underway, this will have negative connotations for employment. The NAHB Housing Index tends to lead unemployment by around 12 months and indicates the latter is set to rise significantly over the next 6-12 months.

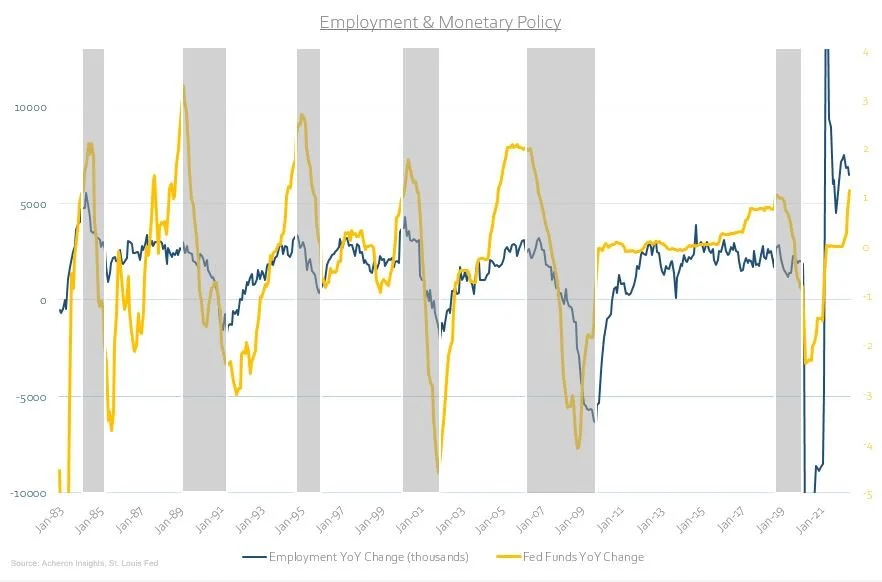

With these trends clearly weighing on the business cycle (I detailed the poor outlook for the growth cycle in depth here), a rise in unemployment seems likely. Remember, employment is a lagging indicator of the growth cycle. So, with the ISM Manufacturing PMI likely headed sub-50 in the coming months, a rise in unemployment will follow. The following chart does an excellent job in illustrating the flaw in the Fed’s mandate of full employment and just how lagging their reaction function is to the business cycle itself.

Quite clearly we can see how the rate-of-change in employment tracks the business cycle by around 6-12 month (though generally in a more volatile fashion).

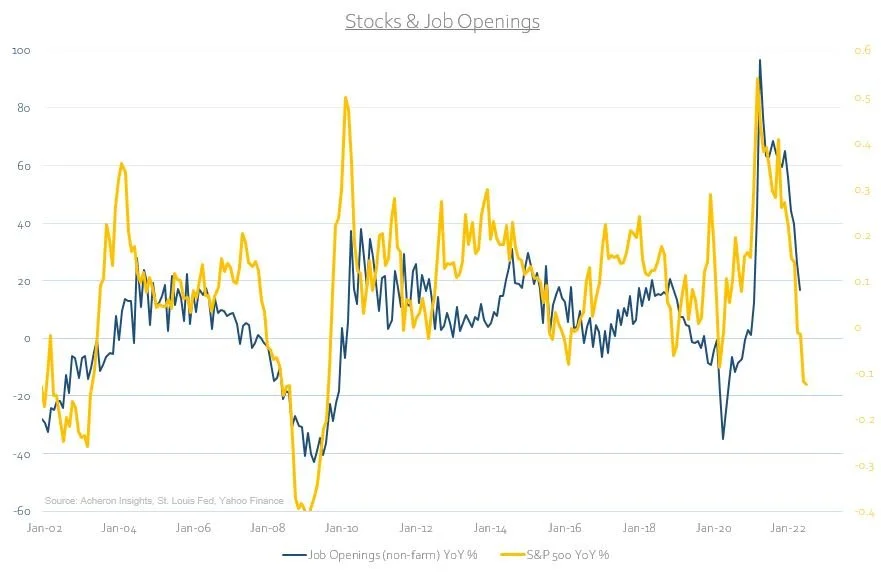

Important to this relationship is the financialisation of the economy. Through decades of increasing reliance on monetary policy and the Federal Reserve’s growing influence on financial markets, we have seen employment (or more accurately job openings) becoming increasingly tied to the performance of the stock market. As stocks have fallen, job openings and thus employment follow suit. We now live in a world where the economy and the stock market are becoming one and the same.

The implications of the financialisation of the economy are considerable, particularly from a monetary policy perspective. The Fed is simply unable to kill inflation and wages without triggering a significant correction in equities. Or alternatively, the Fed knows this and as a result are eager for the stock market to fall as a mechanism to destroy demand and kill inflation. I will discuss financliastion in greater detail below, but, one way or another the implications are clear.

Leading indicators of wages

Turning now to wages, we are beginning to see a number of leading indicators of wage growth signaling a deceleration may be on the horizon. While few are foretelling that wages will fall on an absolute basis, we are starting to see signs that on a rate-of-change basis wage growth may be peaking. Remember, what matters predominately from an asset market and policy setting perspective is the rate-of-change in economic data.

Indeed, in comparing the number of Job Openings versus Unemployed Persons, we can see this ratio has rolled over substantially on rate-of-change basis. This ratio tends to lead wage growth by around nine months.

Likewise, the Quit Rate has also fallen significantly on a rate-of-change basis. This indicator too portends wage growth should normalise over the next nine months.

The number of Job Opening less Hiring’s is also signaling wage pressures may be peaking.

The same can be said for Small Business Job Openings, per the NFIB Small Business Survey. Small businesses simply have no scope to increase operations or expand their businesses at present as their resources are being consumed via higher wage requirements for existing staff, higher input costs and waning consumer demand.

Unsurprisingly, the NFIB Small Business Survey Plans to Raise Compensation component has rolled over significantly of late. This tends to also lead wage growth by around six months.

Though we seeing no indication of any material relief to the tight labour market any time soon, from a rate-of-change perspective there are a number of leading indicators suggesting wage pressures may be peaking and a deceleration in the rate-of-change in wage growth may be imminent.

The labour market, financialisation and monetary policy

As I have touched on, employment data and wages are very much lagging indicators of the economy. They tell us not where the growth cycle is headed, but instead are consequences of current trends in economic growth and financial markets. Thus, we can glean little from a trading nor asset allocation perspective from analysing wages and employment. Importantly however, what we are able to ascertain from examining these trends are the likely future monetary policy actions of the Fed. Recall, the Fed’s mandate is full employment and price stability.

Herein lies the power of understanding where employment and wage growth are headed; it allows us to better understand the likely near term monetary policy actions of the Fed and to ascertain when the data suggests a policy pivot could occur. This is of particular importance given the increasing financialisation of the economy and the influence of monetary policy on financial assets.

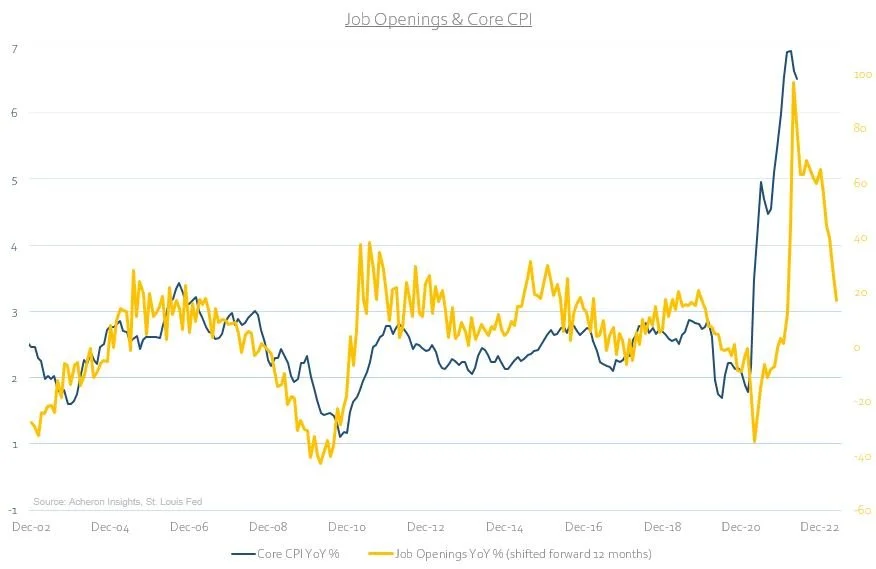

Indeed, not only does the stock market lead job openings, but job openings lead inflation itself.

It is through this cycle we can see the impact of a financialised economy. Easy monetary policy leads to higher stocks; higher stocks lead to more job openings; more job openings lead to higher inflation and low unemployment; higher inflation and low unemployment lead to tighter monetary policy; tighter monetary policy leads to falling stocks; falling stocks lead to falling job openings; falling job openings leads to falling inflation and rising unemployment; falling inflation and unemployment lead to easy monetary policy; easy monetary policy leads to higher stocks. And so the cycle goes. What’s more, with the continued rise in (and consequences of) passive investing and how these systematic flows are linked to employment, we are unlikely to see this relationship subside anytime soon.

Thus, as the Fed continues down its path of monetary tightening as governed by their mandate of stable prices and full employment, we are slowly seeing signs these actions are at least influencing a slowdown in wage growth and rise in unemployment. We ought to see these trends show up in the hard data points as we close out 2023.

This is where the rubber meets the road, over the past three decades any material drop in employment has seen the Fed not only stop raising rates but move to cut rates entirely and ease monetary policy. If this pattern holds, once we see a spike in unemployment and wage growth subside, the Fed will be done tightening.

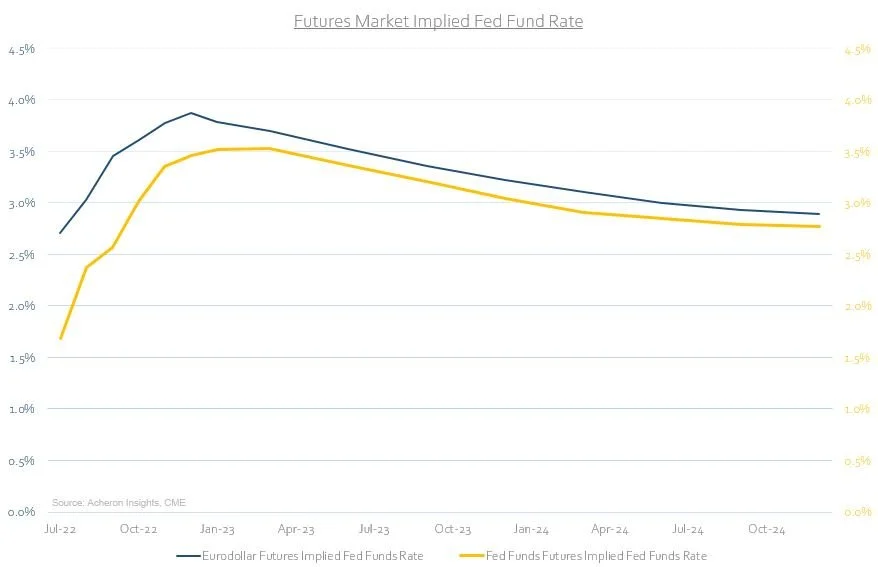

This is very much what the futures market is pricing in, suggesting the Fed will be cutting rates come 2023.

We still have an undersupply of workers, for now

However, 2023 is still some way off. There likely remains more pain to come from the present until the labour market adjusts to reflect the dire economic environment we currently find ourselves in. With policy makers focused on the lagging signals from the labour market, the Fed will continue to tighten monetary conditions for the time being.

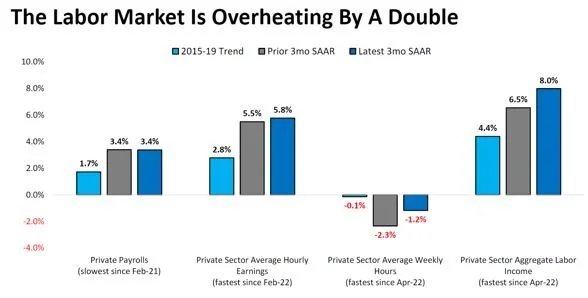

Indeed, this is to be expected when the labour market is experiencing extreme tightness relative to recent history. Per the excellent work of Darius Dale and 42 Macro, Private Sector Aggregate Labour Income growth is currently double its pre-pandemic five-year trend and significantly higher than its previous three-month annualised trend.

Source: 42 Macro

Though these pressures ware likely to subside as we close out the year, as it relates to today, the Fed is being guided in their tightening path by data points such as this and are likely to continue to tighten until the data says otherwise. Unfortunately, this could well lead to a situation where policy makers over-tighten monetary conditions into a material cyclical downturn. A policy error seems like the logical outcome when said policy is based on lagging data.

A quick word on the labour force participation rate

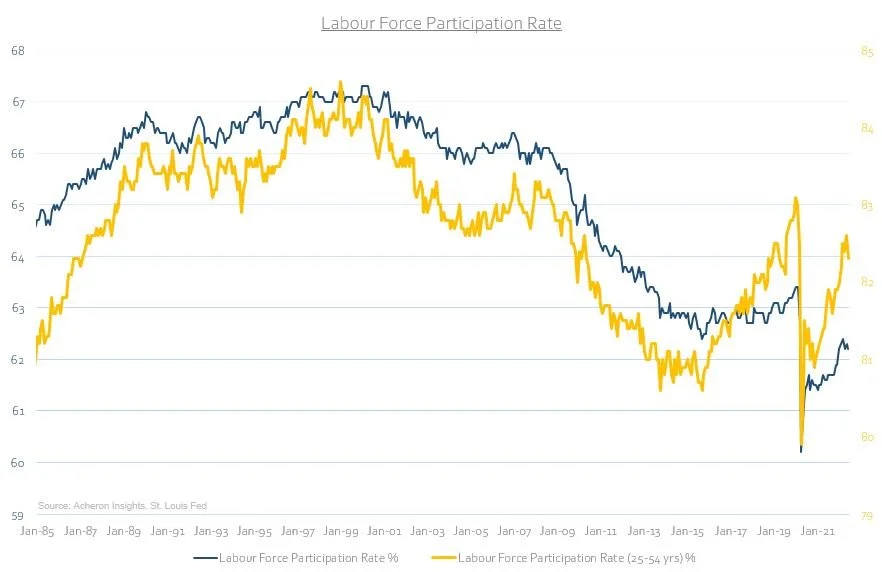

Integral to any discussion on the labour market is considering the trends in the labour force participation rate. As has been the case over the past 30 years, this ratio continues to make lower highs with each and every business cycle. This is true for both the labour force participation rate as a whole and the even more important 25-54 age demographic. The current labour force participation is unimpressive.

Through each business cycle we come through the other side with fewer workers; this is an important trend investors need to understand. With fewer workers, we have fewer contributors to economic growth and fewer workers to fill outstanding job vacancies. By analysing this trend in the labour force participation rate, the undersupply of labour and tight labour market we have at present makes sense. Unless we see a significant rise in the labour force participation rate through the next growth cycle upturn, we ought to see more persistent wage growth pressures going forward than we are accustomed to.

From an economic growth perspective the implications are equally profound. Indeed, important data points like unemployment should be cross checked to see whether the labour force participation rate is increasing or decreasing. A falling unemployment rate due to a falling labour force participation rate is not positive for growth.

If an increase in wages is offset by a reduction in the labour force, then the net benefit to overall growth is somewhat offset. From a growth perspective, we much consider wages in context to the labour force participation rate.

Conclusion and final thoughts

For now, the labour market is historically tight and will continue to pressure the Fed to pursue their tightening agenda by raising rates and tightening financial conditions. The Fed have stated they are going to be data driven in their tightening agenda, so with the near term unlikely to see a material change in data from the labour market, there is reduced scope for a Fed pivot. This will continue to add fuel to the recession fire.

However, we must remember that employment and wages are lagging economic indicators, and as I have opined herein, the leading indicators of employment suggest a rise may be forthcoming along with a relief to wage growth pressures. Given the importance of the labour market in setting monetary policy, a material pick-up in the unemployment rate would be a data driven signal for a dovish pivot, with the possibility this could occur as soon as the turn of the year.

For now, who are we to fight the Fed.