Beware The Credit Cycle

The credit contraction is only just beginning

Our entire financial system revolves around credit. This includes the ability to access credit for new loans, and more importantly, the refinancing of existing loans. Unfortunately, credit creation is pro-cyclical, and, when yields rise and liquidity is removed, credit creation tends to fall. This contraction in credit has significant implications for the economy.

At the center of any credit contraction are the banks, for it is they who are the primary providers of credit and thus money creation. Although the bank runs and bail outs of Silicon Valley Bank and the like are probably past us, they are likely to be accelerants of this downturn in the credit cycle. Bank lending practices have tightened dramatically over recent quarters. The latest Federal Reserve loan officer survey highlighted how restrictive commercial banks’ lending practices are becoming, with credit availability across the board reaching the tightest levels since the COVID-19 recession, and prior to that, the GFC. This data has yet to be released for the post-SVB period so one would suspect the majority of small and medium banks’ lending practices have only become stricter since.

As such, small businesses are now feeling the pinch. The NFIB Small Business Survey’s Availability of Loans reading has recently reached its lowest point in nearly a decade. This will only worsen as the credit cycle downturn continues.

Again, the economy runs on credit. When banks become risk averse and more restrictive in their lending practices, the availability of capital for not just small businesses but corporates and consumers as a whole reduces precisely at the time where it is most required. In a way, the credit cycle is self-fulfilling, and its inevitable contraction is perhaps the final destination of the path of monetary tightening and extraction of liquidity the Fed has set us on.

This is why tighter monetary conditions almost always end badly.

Source: Bank of America

What is driving credit spreads higher?

One of the best leading indicators of credit spreads is of course central bank policy rates. Given how globalised our financial system has become and the prominence of the Eurodollar, assessing policy rates through a diffusion index of the G20 central banks tends to provide a fairly reliable lead on where credit spreads are heading over the following 12 months. The lags of monetary policy are long and variable, and the credit markets are seemingly yet to feel their effects.

Likewise, interest rates suggest spreads are set to rise materially over the coming quarters.

While policy rates and interest rates provide a solid long-term lead on the direction of credit spreads, it is largely through bank lending standards to which these trends actually influence the economy and thus see spreads widen. As we saw earlier, lending standards have been rising materially in recent times. The yield curve suggests this will continue.

Unsurprisingly, tightening lending standards is itself a leading indicator of loan growth.

So, as access to credit becomes increasingly difficult as lending standards tighten, this almost always result in higher credit spreads. As it stands, the divergence between the two is remarkable, particularly so considering the last divergence of similar magnitude (February-March 2020) was accompanied by material fiscal and monetary support. Now, we have the Fed and central banks worldwide largely unable to provide liquidity support (at least not yet), but are instead acting to further tighten financial conditions.

Credit crunch incoming

As credit spreads rise, there are set to be material consequences for both the financial and real economies.

In terms of corporate profitability, credit spreads themselves tend to lead earnings by around six to 12 months. Given how well spreads have held this year, we may see Q2 earnings hold up in-line with estimates. Should spreads indeed blow-out as the leading indicators of the credit cycle suggest, then earnings should follow suit and estimates beyond the first half of 2023 will likely prove foolish.

Of course, higher spreads and lower earnings will eventually lead to increased delinquencies and bankruptcies in the corporate sector.

And thus eventually lead to layoffs and a rise in the unemployment rate.

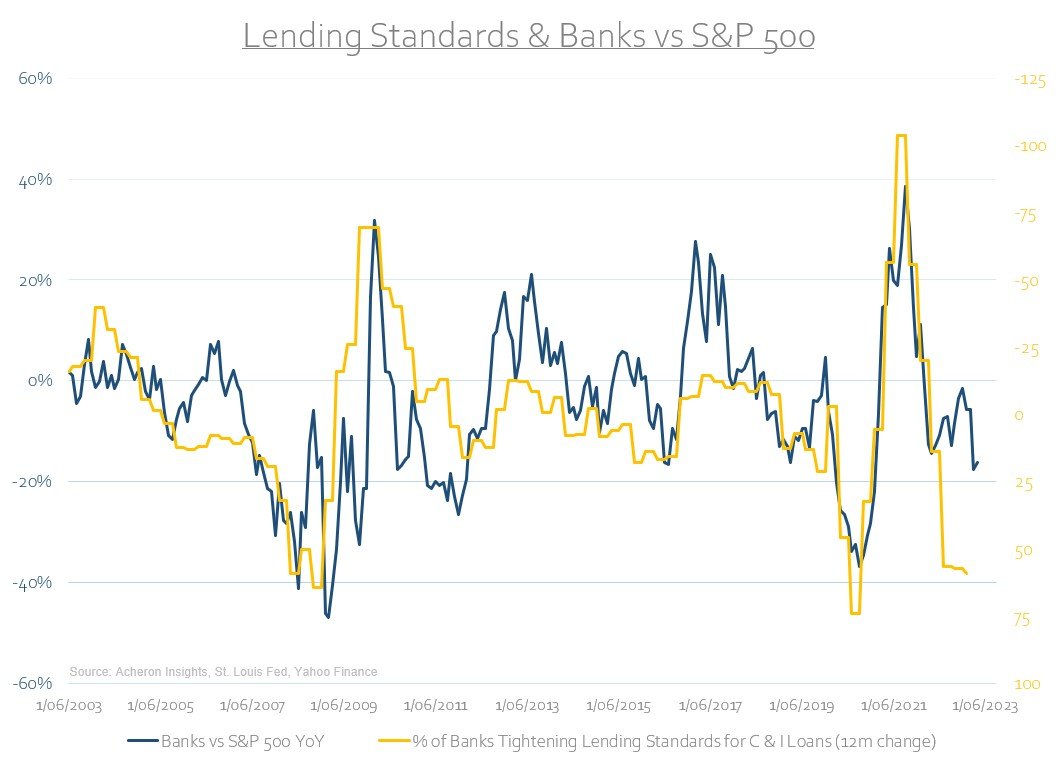

As banks are at the center of the credit cycle, history suggests increasingly restrictive access to credit will ultimately hinder the performance of bank stocks relative to the broad market.

In terms of the equity complex overall and which sectors are most vulnerable to tighter credit conditions, the below chart illustrates this by assessing the correlations between the price performance of the main equity sectors and credit spreads. The greater the negative correlation, the more exposed the sector is to a downturn in the credit cycle, which would see spreads widen. Outside of financials and banks, the industrials, real estate and communication services sectors have generally seen the biggest falls in share prices when credit spreads have widened. Meanwhile, defensive sectors such as health care and utilities, as well as commodity sectors in energy and materials have held up okay in such an environment in recent times.

Households will feel the pinch

The impact of contracting credit conditions is not just limited to the corporate sector, consumers will feel the pinch as well. As real income growth turned negative for much of 2021 and 2022 as inflation growth outpaced wage growth, the household sector increasingly relied on credit cards as a means to fill this gap.

As a result, overall consumer credit growth is at its highest level in over 20 years.

While this is all well and good when interest rates are at generational lows, when interest rates, mortgage rates and in particular, credit card rates see their largest and swiftest increase in half and century, the implications are likely to be severe.

Don’t be surprised then to see household sector delinquencies and even bankruptcies continue to accelerate upward. As reported by the Washington Post, “nearly 25 million people are behind on their credit card, auto loan or personal loan payments”, while “many households are also behind on their utility bills, with 20.5 million homes having had overdue balances in January”. Clearly, households are feeling the pinch.

The commercial real estate section is also particularly vulnerable

Unfortunately, the commercial real estate (CRE) sector looks likely to be the hardest hit should the forthcoming credit contraction play out. As it stands, the CRE industry is facing a series of headwinds, including:

Rising interest rates, with roughly 40% of CRE mortgage needing to be refinanced over the next three years;

A contraction of credit availability, which will only exacerbate this problem. Roughly 80% of CRE debt is issued by small and medium sized banks - those most likely to be the stingiest with their lending standards going forward;

Higher capitalisation rates, leading to falling property values; and,

The continued demise in office building utilisation. As it stands, a record 30% of San Francisco office spaces are vacant with New York also seeing record high office vacancies.

All these factors, in addition to a slowing economy point to a situation whereby potential investors will simply look elsewhere for more attractive investment opportunities with less risk. Why invest in commercial real estate (particularly office buildings) when you can buy short-term government debt yielding ~5%. It’s a no brainer. What’s more, vacancies should continue to fall in the event a growth slowdown leads to a spike in bankruptcies. Clearly, the CRE sector - and in particular the office building sector - should continue to be stressed going forward.

So, what is the market pricing in?

As investors, it all comes back to what asset markets are pricing in. Credit spreads are pro-cyclical and have historically tracked the business cycle well, which I have proxied below via the ISM Manufacturing PMI. Right now, credit markets are not reflective of this outlook for the credit cycle and are pricing the PMI at around 55…

While junk bonds themselves have done a better job of pricing in any kind of business cycle downturn, it is still difficult to argue they have priced in the entirety of any forthcoming contraction in the credit cycle or business cycle. Now is not the time to be taking considerable credit risk.

For those who believe this growth cycle downturn will culminate in recession, comparing the current drawdown to the average of those seen in past recessions illustrates how poor a job credit spreads have done at pricing in this outcome. Stocks on the other hand (at least the broad equity indices, have done a far better job).

Ultimately, given the link between rising credit spreads and volatility, should credit spreads widen then higher volatility will ensue. Stock prices tend to fair poorly in an environment of such uncertainty, regardless of how much on a potential recession they have priced in.

Fortunately, it’s not all doom and gloom

While a credit cycle downturn bodes poorly for many areas of the economy. We are very unlikely to see any GFC-type credit event. As I have argued numerous times, households (and corporates) are on solid footing from a structural perspective. This is a primary reason why the US economy has proved robust and resilient in the face of the swiftest tightening of financial conditions in recent history.

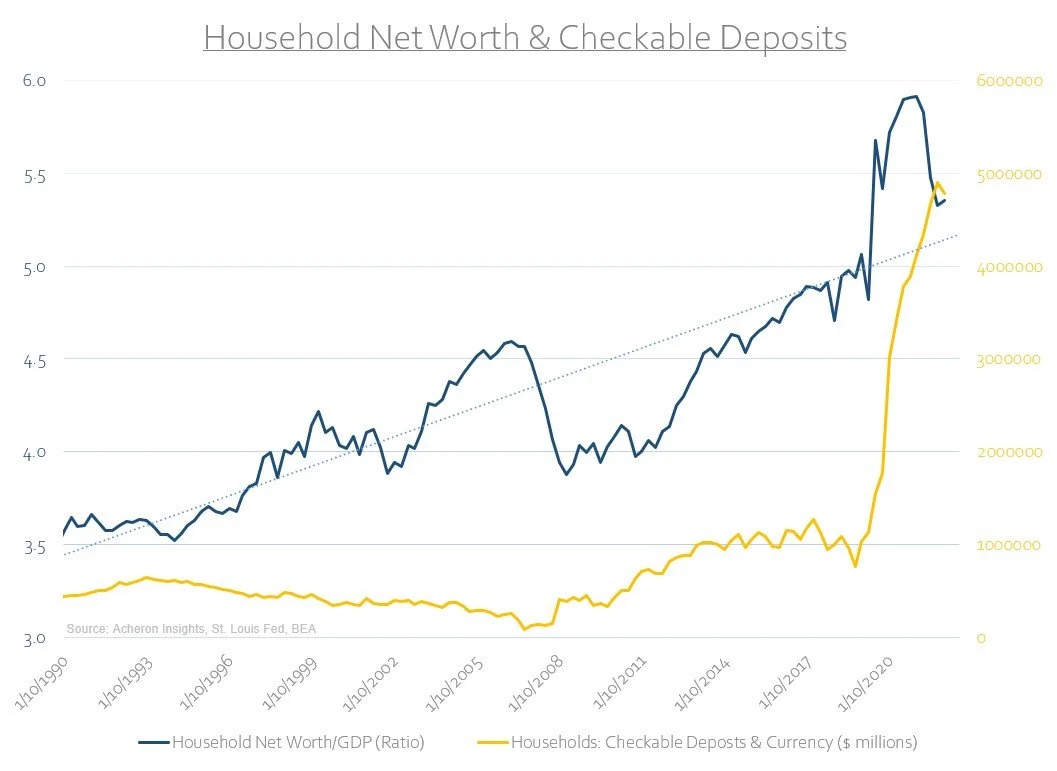

Firstly, thanks to a record bull market in financial assets in recent times and the impact of direct fiscal payments, household net worth remains well above trend while household checkable deposit levels are beyond anything seen in recent history.

Likewise, debt serviceability is also relatively robust. Mortgage debt service payments as a percentage of disposable income are at secular lows while consumer debt service payments as a percentage of personal disposable income are roughly in-line with their long-term average.

The same can be said of household total debt levels relative to disposable income.

However, although households and consumers are on solid footing from a structural perspective, the cyclical outlook is still worrisome. Just because we won’t get a GFC-type credit event doesn’t mean the credit cycle downturn won’t have material implications on the outlook for the cyclical business cycle. Again, this is not a good time to be taking meaningful credit risk.

. . .

Thanks for reading!

If you would like to support my work and continue to allow me to do what I love, feel free to buy me a coffee, which you can do here. It would be truly appreciated.

Regardless, feel free to share this with friends and around your network. Any and all exposure goes a long way and is very much appreciated. Thanks again.