The Consequences of Passive Investing

“If you push indexation to its logical extreme, you will get preposterous results” - Charlie Munger

The rise of passive investing over the past 30 has revolutionized the way investors obtain exposure to the worlds equity markets. The introduction of index funds as far back as the 1970s and more recently, the rise of exchange-traded funds since the 1990s has provided a cost effective way for institutions and individual investors alike to participate in financial markets without the need for the traditionally more costly active managers.

It is true the introduction of these low-cost investment vehicles has been beneficial for investors, resulting in passive investing becoming the primary investment vehicle of choice for many. Particularly within the past decade, we have seen flows into passive investment vehicles continue to grow at the expense of traditional active managers, leading to the rise of financial behemoths Vanguard and Blackrock. However, whilst it is rational for one to argue this rise of passive to be beneficial for investors, what these institutions claim as being a low cost way to invest may come at great cost in the long run.

Passive investing appeals to those looking for a free lunch, but as we know, there is no free lunch in financial markets.

The rise of passive

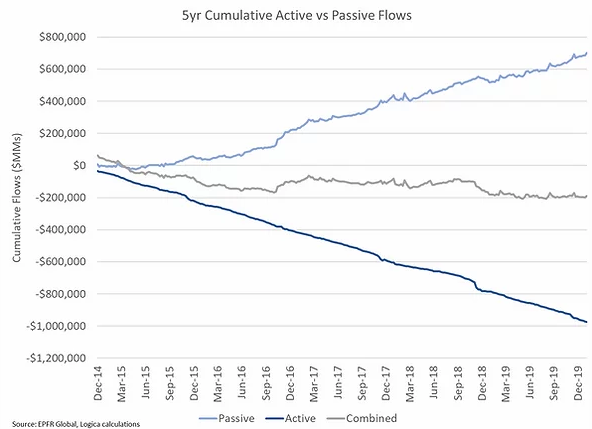

We can see how the flow of funds into investment vehicles has skewed towards passive (in the form of ETFs) at the expense of managed funds (who are predominately actively managed). This trend has been particularly noticeable over the past five years.

Source: St. Louis Fed

Michael Green (formerly) of Logica Funds, whose work on the impacts of passive investing has become renowned of late and from which the basis of my research has been sourced, confirms his dynamic of flows into passive in a recent paper published by his firm.

Source: Mike Green, Logica Funds - Policy in a world of pandemics, Social Media & Passive Investing

The fundamental basis behind passive investing becoming the primary way investors allocate capital has been easy to justify and rightfully so. Ultra-low fees, simplicity, tax-advantages (via ETFs) and of course superior investment returns relative to actively managed funds. I myself have borne witness to this dynamic first hand. Working within a financial advisory firm which has historically favored the use of active managers within our clients' portfolios, have extensively incorporated the use of index funds over recent years, a change which has only been sped up by the ease of justifying the superior performance and lower cost to clients. It has become increasingly difficult to recommend the use of active managers in a world where fees and performance are so heavily scrutinized.

The issues with passive

Whilst the appeal of passive investing is hard to ignore, there is an increasing number of fundamental issues with passive investing itself of which most investors are not aware or are ignorant of. The general theory behind passive stems from the efficient market hypothesis, theorizing that current prices of securities reflects all available information (i.e. the market is efficient), and thus active managers are not able to beat the market if they are using publicly available information. The theory of passive as posited by Bill Sharp, assumes passive investors only wish to partake in the movement of asset prices and thus will hold the market portfolio, consisting of all securities within an entire investible universe (both public and private, which in itself is of course impossible).

The idea of passive investing being “price-takers” and are thus having no impact on market prices is ridiculous. Whilst it is true this would be the case if the passive vehicles were already holding the market portfolio and were not receiving any inflows or outflows of capital, we can see above this is not the case. Passive is only passive if it is not buying or selling. Passive investment vehicles are continuing the see inflows, which, as passive investment vehicles are fully invested at all times, means they must be buyers of securities.

How can a passive investment vehicle be truly passive if they are continually buying securities as more and more money flows into their strategies? As noted by Mike Green in Logica Funds’ paper Policy in a World of Pandemics, Social Media and Passive Investing “these are not passive investors - they are mindless systematic active investors with zero interest in the fundamentals of the securities they purchase”. Passive is supposed to benefit via market participation without influence; this is not the case. Passive has become such a dominant player that it may now be the dominant player in the markets.

Another issue of passive investing is the construction of underlying indices themselves which the passive vehicles aim to track. This issue largely stems from the fact that in their origin, the largest and most commonly known indices of today such as the S&P 500, were originally constituted as observation vehicles. Most of these indices predate the notion of passive investing and the idea that there would be investment vehicles tracking their performance was not a consideration as part of their creation.

What has happened as a result of these indices being tracked for investment purposes is that in order for their constituents to be investable, they must meet certain float and liquidity requirements. The most prevalent example of this can be seen by examining the S&P 500 index itself. What was initially a market capitalization weighted index, in 2005 the weighting methodology was changed to a float-adjusted market capitalization weighted index.

The primary driver of this change was the capacity of the companies within the index to absorb the ever increasing flow of capital into passive investment vehicles, thus increasing the assets under management and the ability to make index funds profitable for firms like Vanguard and Blackrock given their low fees. The incentive thus became for the providers of passive vehicles not to accurately track the historical S&P 500 index, but to allow as much capital as possible into these passive vehicles.

There is a critical point to understand in relation to how a float-adjusted market capitalization weighted index varies its security selection to the historical capitalization weighted indices. This act of adjusting from market-cap weighted to float weighted removes the proportion of shares owned by company insiders from its market-cap. What this means is, companies with a large portion of their publicly traded equity owned by their executives and senior management receive a smaller weighting in the index relative to companies who have a lesser amount of insider ownership, and thus a larger float.

What is effectively happening is companies whose managers have been largely responsible for their success, and thus own a large portion of their equity receive a smaller weight in the index, and, when these insiders sell down their holdings of the company (perhaps due to a fundamental problem or macroeconomic headwind facing the business, or their retirement) their weighting in the index increases, as their float-adjusted market cap increases due to the lesser insider ownership.

Likewise, in a situation where company insiders deem that buying their stock would be attractive, whether for valuation reasons or fundamental prospects, their weighting in the index is decreased. This dynamic seems to be in direct contrast to how most active managers would have historically selected potential opportunities and an important dynamic that must be highlighted to investors.

What’s more, the historical performance of the S&P 500 index was not adjusted downwards upon its move from a cap-weighted to float-weighted index to reflect the lesser performance associated with historically investing in companies without significant insider ownership. Steven Bregman of Horizon Kinetics, another well known investor who has undertaken expensive research on the impacts of passive, has highlighted this dynamic and has stated that a notable amount of the historical performance of the S&P 500 was due to its weighting to companies with a high level of insider ownership. It must be noted that the S&P 500 index of today, and all indices whose requirements have been adjusted to reflect liquidity and float constraints, are not the same indices whose historical performance it aims to replicate and whom most investors believe they are investing in.

Whilst adjusting the investability of the index to be able to absorb the required level of capital makes sense, this flies in the face of the core assumption that passive investing does not impact market prices. These float and liquidity requirements are directly influencing the level of capital that flows into specific companies, favoring those with a higher float and thus bidding up their prices relative to companies with a larger level of insider ownership.

A similar dynamic can be observed by examining how passive flows affect the prices of high-yielding stocks relative to low-yielding or non-dividend payment stocks. Generally, when a company goes ex-dividend, its market capitalization should fall to reflect the value of the dividend to be paid to shareholders. If a passive vehicle such as an index fund of ETF were to reinvest the dividend it receives, it would do so in the same manner that any inflow into the fund would be invested, via their weighting methodology.

This means that if the dividend paying company’s market capitalization were to reduce following its dividend payment, then the dividend paying company would receive a proportionately lesser amount of capital being reinvested relative to low-yielding or non-dividend paying companies. This dynamic has been highlighted by quantitative fund manager Corey Hoffstein of Newfound Research in his recent paper, Liquidity Cascades.

In this paper, Corey presents an analysis of two long/short strategies, “the first goes long high-yielding stocks and short low-yielding stocks (Hi 30 - Lo 30), which is a classic proxy for value investing. We can see that since 1927 this has been a winning, albeit volatile, trade, with the exception of recent history. The second strategy is long high yielding stocks and short no yielding stocks (Hi 30 - No). Curiously, this is a volatile loser (suggesting that no-yielding stocks outperform) until the early 1990s, at which point it become far less volatile. The consistent out-performance of no-yielders and growing outperformance of low-yielders may suggest a potentially growing, distortive impact of basket pricing (which is how passive ETFs are traded)“.

Source: Corey Hoffstein, Newfound Research - Liquidity Cascades: The Coordinated Risk of Uncoordinated Market Participants

Furthermore, this index construction is also particularly relevant and distortive to passive vehicles tracking bond indices. Bond indices were created to give investors an idea of the yield for a particular set of bonds, of which the yields of the underlying bonds within that index are weighted by their market price, meaning the yields on the bonds with the highest value are given the biggest weighting and vice-versa. What this means is, as interest rates decline and the corresponding price of bonds increases, the most expensive bonds will see their share in the index grow at an increasing rate, even though their yields are falling.

A prudent investor would assess a company’s credit rating and its fundamentals prior to loaning it money, the same way a bank assesses the credit rating and financial position prior to lending money for one's mortgage. Their weighting in an index is determined solely by price, with no consideration given to their credit rating or their actual ability to repay their loans. The idea of investing in fixed income purely because their price has increased is akin to momentum investing in bonds.

It is clear that passive investing does not meet its own definition that you only “hold” the securities. The idea that passive is truly passive is absurd. Passive vehicles allocating capital on a float-adjusted market capitalization basis is presuming the market is efficient and current prices reflect all available information. So long as the flows into passive vehicles exceed the outflows, or inversely the outflows exceed the inflows, along with the dynamic of biasing companies with a lesser insider ownership and lower dividend yield, they must transact and thus they must influence prices. What passive managers truly are large institutional active quantitative managers with absurdly simple systematic rules.

The consequences of passive investing

What becomes even more important than the issues surrounding how the passive vehicles invest is the potential long-term consequences an ever increasing passive share will have on the market. Thankfully, there is a growing amount of research into these potential concerns by several well known investors who have undertaken an incredible amount due diligence to understand its impacts. The aforementioned Mike Green being one, whilst Christopher Cole, the well known CIO of the long volatility hedge fund Artemis Capital is another. Both are two of the best thinkers in finance today.

If we buy into the notion that passive investing is beginning to impact the markers, we would expect to see momentum characteristics dominate returns. As the prices of individual stocks rise, their weightings within the indices would increase, thus increasing the incremental flow of money into these companies via passive vehicles. There is evidence confirming this phenomenon since the introduction of index funds.

Source: Mike Green, Logica Funds - Policy in a world of pandemics, Social Media & Passive Investing

Source: Corey Hoffstein, Newfound Research - Liquidity Cascades: The Coordinated Risk of Uncoordinated Market Participants

We can see above that particularly over the past five to ten years, momentum based strategies has significantly outperformed value based strategies as the flows into passive at the expense of active has accelerated. This trend can be further extrapolated to the outperformance of large-cap equities versus small-cap equities given large-caps increased weightings in the indices is reinforced by passive.

Furthermore, we would expect to see an increase in correlation of securities within an index as flows into passive exchange-traded and index funds are largely traded as “baskets”, with no consideration given to the price of the individual securities.

Source: Mike Green, Logica Funds - Policy in a world of pandemics, Social Media & Passive Investing (historical co-movement of the S&P 500 adjusted for volatility)

This increased correlation (or as Mike Green and Logica have used co-movement - which is an extended data series that can be interpreted in a similar way to correlation) among securities is even more accentuated during periods of heightened volatility and more extreme market moves, primarily as a result of hedging activities among dealers and market makers during times of market “normalcy", which dampen volatility as they hedge institutional investors yield hunting short call options (i.e. short volatility) strategies.

Source: Mike Green, Logica Funds - Policy in a world of pandemics, Social Media & Passive Investing

This increased level of correlation among securities raises issues regarding diversification for equity investors. If an equity portfolio consisting of 30 or so companies was once considered diversified, given they now are increasingly priced as a group during periods of increased volatility (a time when diversification is needed most) due to the rise of passive, we must reconsider how diversified equity portfolios truly are. Perhaps, such a way to achieve sufficient diversification would be to allocate to securities that are largely excluded from the major indices and their flow of funds, such as companies with large insider ownership. However, if this thesis proves true then this would likely lead to a drag on portfolio returns, which of course is an excellent way to get an active manager employing such a strategy fired and replaced with a passive manager.

What we would then expect to see going forward is an increased likelihood of momentum, growth and trend following strategies outperforming traditional fundamental based investment strategies such as value (at least from a quantitative perspective). Corey Hoffstein discussed these dynamics of increased market fragility caused in part by the influence of passive in his paper referenced above, illustrating that investment strategies can largely be classified as either convergent or divergent strategies. Convergent being those who rely on mean reversion (i.e. value, whose managers will sell overvalued companies relative to their fundamentals and buy those deemed undervalued relative to their fundamentals), and divergent being those whose performance is a function of price continuation in a particular direction (i.e. momentum or trend following).

If passive is in itself a divergent strategy, then as the majority of inflows into the market are done so via these passive vehicles, we would expect to see a continuation of the outperformance of momentum based strategies relative to their convergent counterparts. Furthermore, if we continue to judge investment performance on a comparative basis relative to a passive benchmark, those active managers who do not adhere to a divergent strategy would in all likelihood continue to underperform. Those underperforming managers would thus see outflows of capital as asset allocations pile into strategies that have demonstrated recent outperformance. This dynamic only acts to further reinforce the momentum factor in self-reflexive manner.

Again, there is certainly evidence to suggest this is the case, as highlighted above. Likewise, if we are seeing an increased correlation among securities, we would expect to see a lesser response in the prices of those within an index to earning announcements. This indicates a clear roadblock to process of price discovery within markets, which of course is in direct contrast with the efficient market assumptions behind the theory of passive investing.

Now, if the momentum dynamic reinforced by passive continues into the future, it is important to consider how this will affect equity prices relative to their fundamentals. As we know passive strategies trade in a flow of funds basis, and do not tactically respond to external market signals in the manner that an active manager would display risk-on or risk-off characteristics, so long as the passive inflows exceed the outflows from both passive and active vehicles, this would result in a constant bid being present for securities. Both Mike Green and Chris Cole have done work on modelling the dynamics of this dynamic and its potential for “discontinuous” pricing of securities.

One of the roles of discretionary active managers within markets has historically been to allocate capital to business’s whose fundamentals, prospects and valuations are deemed favourable and expected to generate future economic growth. For the most part, we would expect active managers to be more willing to allocate capital to companies who are cheap relative to their fundamentals, and less willing to allocate capital to companies that are expensive relative to their fundamentals and whose prospects are poor. This fundamental based price discovery aspect of the markets is not present within passive strategies, and will increasingly be less present in the markets as passive continues to gain market share.

Passive's willingness to buy securities is not a function of fundamentals or valuation, it is a function of flows. What this means going forward is that flows become the key driver of returns and are likely inflationary for asset prices. If the role active managers play in the market continues to diminish, the market itself loses the ability to reset prices during excessive price swings in a certain direction. As long as the flows in exceed the flows out, price theoretically can rise (or fall) exponentially.

A simple way of assessing the price inflationary forces of passive is by looking at the valuation of the median stock in the S&P 500, which as measured by forward price/earnings “is now in the 100th percentile of historical levels”, as noted recently by the Wall Street Journal, and illustrated below as measured by median price/sales.

Source: Mike Green, Logica Funds

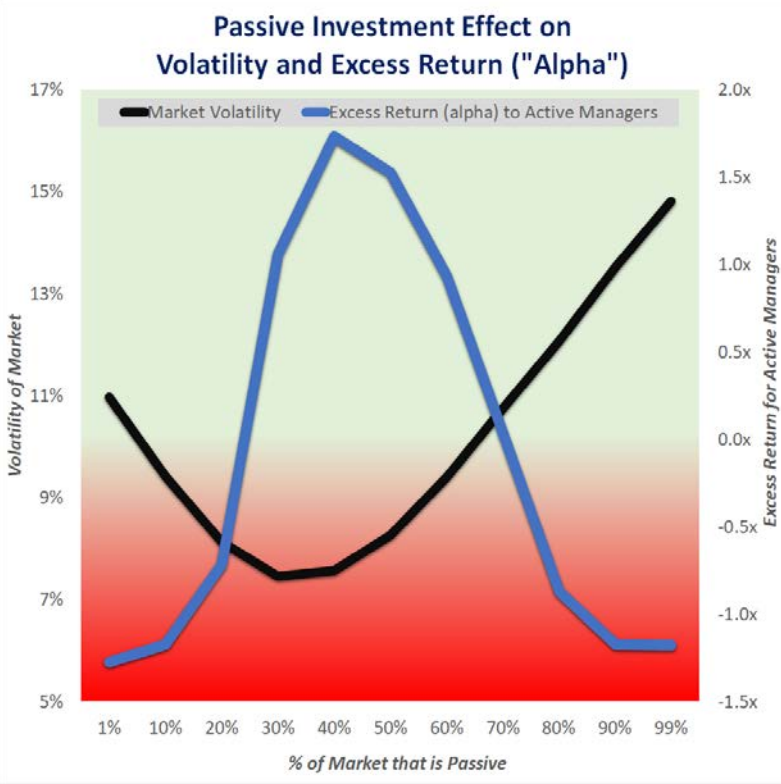

In a letter to his investors in July 2018, Chris Cole modelled a market simulation to test the impact of passive investing. In this simulation, Chris noted that two key themes emerged when the market became dominated by passive; amplified volatility (a dynamic I will discuss further below) and diminishing excess returns available to active managers. He found that active managers' alpha peaked when passive comprised approximately 42% of market share (which as he notes is likely to be a far lower threshold in the real world), before dramatically dropping off as the passive share continues to rise. Furthermore, he notes that when passive participants control 60%+ of market share, the simulation becomes increasingly unstable and prices are subject to extreme volatility and wild trends. An illustration of this model can be seen below.

Source: Chris Cole, Artemis Capital Management - Letter to Investors July 2018

There is clearly a self-reinforcing convex nature to how passive can impact prices. Indeed, another factor reinforcing this dynamic is the lack of any meaningful allocation to cash within these passive vehicles. As their aim is to “participate” in the market, then by default they are fully invested at all times with no discretionary allocation to cash. It makes intuitive sense in that this would only serve to reinforce price momentum on both the upside and downside.

Traditionally, when an active manager receives an inflow of cash, they would hold off investing this cash until an attractive opportunity to allocate said cash presented itself. Likewise, when they receive redemption requests, this would be primarily funded from their cash holdings to avoid the need to sell down their holdings. Passive vehicles do not have this flexibility. If they are required to make redemptions, they will sell assets on a systematic basis in order to meet those redemptions, this is an important consideration to how the rise of passive can increase volatility.

This lack of cash held by passive and their systematic mandates is concerning. Indeed, as passive vehicles are unable to make discretionary buys or sells when they receive inflows or redemption requests, this same systematic trading can only serve to reinforce extreme price swings in scenarios when active managers decide to buy or sell in a risk-off or risk-on manner when the market is dominated by passive. An excellent example used by Mike Green to demonstrate this dynamic is as follows; if you are a manager who wants to buy a security, then unless there is another discretionary trader who is willing to sell to you, you are at the whim of the passive manager as to whether you are able to trade.

As the percentage of active managers continues to decline and the percentage of passive rises, the likelihood of you being matched with another discretionary trader who is willing to trade with you diminishes. As a result, you will in all likelihood be forced to increase the price you are willing to buy in order to attract the active manager to sell that security, or reduce the price you are willing to sell an asset to an active manager.

This will only serve to increase volatility on the upside and downside. Mike has indicated his research suggests that passive market share need only be around 30% before this dynamic begins to have a meaningful effect on prices, and by the time we reach 50% passive, this dynamic will cause market prices to behave in a discontinuous manner, similar to what Chris Cole observed in his model. Mike estimates the US to be around 40%-45% passive at present in terms of market share, whereas the flows into markets being 90%+ passive.

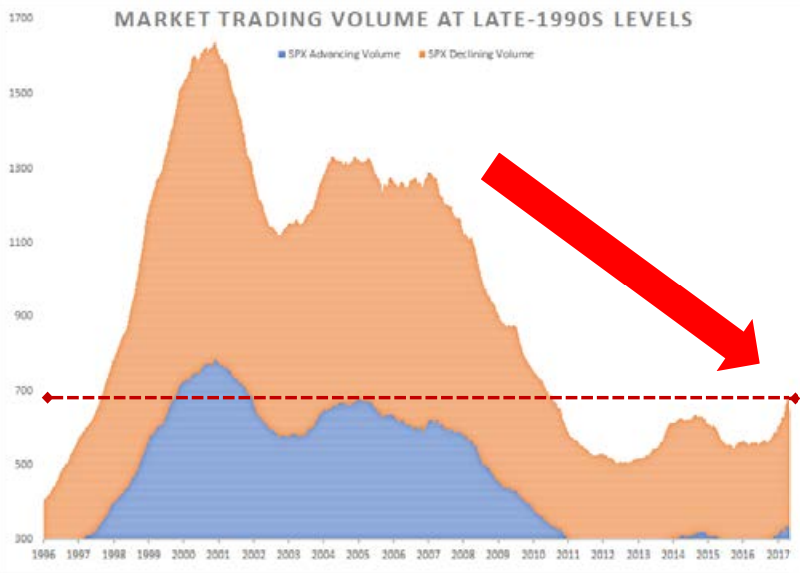

Furthermore, the liquidity of markets and how this would impact a giant systematic wave of price agnostic buying and selling by the passive vehicles will only act to reinforce the volatility and price appreciation effects of passive. For various reasons I not will go into detail within this article, but rather refer you to the excellent work by Mike Green, Corey Hoffstein and Chris Cole on the matter, we have seen the trading liquidity in equity markets dissipate over recent decades.

Source: Mike Green, Logica Funds - Policy in a world of pandemics, Social Media & Passive Investing

Source: Chris Cole, Artemis Capital Management - Letter to Investors July 2018

Reduced market liquidity can only serve to exacerbate the extreme potential volatility environment going forward due to the rise of passive. This is particularly prevalent during period of market stress, as we can see above. During the March lows of 2020, and similarly in early 2018 and December 2018, market liquidity has been at extreme lows. If active managers are selling during such periods, matching them with a willing buyer only becomes more difficult as the level of discretionary managers who would generally be willing buyers at such times are declining, thus, those who are will to step in and provide liquidity are only willing to do so at lower and lower prices, as the price insensitive passive sellers are not able to act in a discretionary matter.

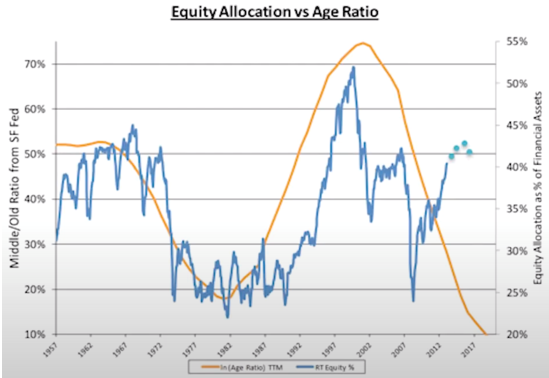

The concern going forward during such environments is that if the outflows of passive players begin to exceed their inflows, not just in periods of market distress but over a longer time horizon. Given the demographics of developed economies, the majority of wealth, and thus the majority of financial assets, are owned by the baby boomer generation who are entering retirement and must be sellers in order to fund their retirement. This is a particularly frightening dynamic, especially considering the baby boomers hold a disproportionate amount of active managers relative to the younger demographics. I recently wrote in depth on how demographics impact financial markets and the economy.

A future of passive

If we believe the impacts of passive highlighted in this article to be largely true, then the question becomes, how does it end? Does the dynamic of passive fundamentally change how the markets behave as long as the flows continue to be biased towards passive, or will there be a catalyst that causes a reversal of this dynamic and a subsequent to return to the more traditional market structure of the past? These are difficult questions to answer.

What we know for sure, and perhaps what will be the tipping point for the potential price appreciation that passive provides is the demographic component of developed economies highlighted above. The baby boomers hold the majority of assets allocated to discretionary managers, whilst the younger generations (particularly the millennials) are almost exclusively buying passive managers as they enter the markets, largely via retirement accounts (i.e. superannuation and 401k's). This clearly only serves to increase the market share of passive, as the younger generations are the buyers of passive and the older generations are the sellers of active.

Furthermore, passive has a clear regulatory advantage over traditional actively managed funds. Retirement savings accounts such as the aforementioned superannuation and 401k’s, are for the most part required to offer an indexed investment option. The millennials contributing monies to their retirement accounts have by and large grown up during a period of passive beating active, and cannot possibly appreciate the value of an active manager and thus have no incentive to allocate capital to anything other than passive. It is hard to see how the younger generations who are the buyers of assets are going to start buying an increasing share of actively managed assets.

The exact opposite dynamic is occurring for the baby boomers, who are now beginning to reach the ages whereby they are forced to take a percentage withdrawal from their retirement accounts each year, or that their target date funds within their retirement accounts are reducing their exposure to growth assets on a systematic basis as they age. There will be a point when they become net sellers of assets.

Source: Mike Green

Furthermore, for those retirees who are mandated to sell within their tax-efficient retirement account, yet the proceeds are surplus to their requirements and are available to be reinvested, there is a clear incentive for them reinvest these monies in more tax-advantaged products such as ETFs (who are largely passive), as opposed to managed funds. Given ETFs allow greater control and flexibility as to how capital gains are realized, this will allow greater control of their taxable income.

The key as to how this may unwind is at which point in time the selling pressure from the retirees exceeds the inflows into passive vehicles. Due to this demographic feature of how capital is allocated and how a significantly greater share of financial assets is owned by the retirees, there will likely come a point in time where the outflows will overwhelm the inflows. Until then, there is no telling how high the constant bid of passive can push asset prices and the level of volatility we may see along the way.

It appears increasingly likely that the consequences of the rise of passive will change the way markets behave for the foreseeable future. The dynamic of performance being driven by their participation within an index and not based on underlying fundamentals has the potential to damage the capitalist system. Companies are not as rewarded for their fundamentals via share price appreciation in the same way as they once were.

In a recent appearance on RealVision, Louis Vincent Gave discussed this very notion of how passively investing is not reflective of a capitalist economy, noting how indexing may be a new form of socialism. If capital is not allocated accordingly to its marginal return but instead is allocated on the basis of market capitalization (a la passive investing), then how is this a reflection of a capitalist economy, let alone encouraging for future growth? Passive investing is socialism of capital allocation within a capitalist society.

It becomes unclear how the mean reverting characteristics that have historically been associated with asset prices are going to be captured. Until the flow of money into passive vehicles changes, whether by regulatory intervention or otherwise, it seems likely we are going to see a significant change in the character of markets. Passive is a self-enforcing, momentum driven strategy. Unless the flows into passive were to change significantly, it is difficult to see how this pattern reverses itself.

We will likely see passive dominance continue until it reaches its conclusion. How preposterous this conclusion will be, only time will tell.