The Economy Is Slowing, But Are We Heading For Recession?

Summary & Key Takeaways

Based on the coincident measures of the business cycle, the US economy continues to perform admirably and display remarkable robustness, particularly in the areas of industrial production and the employment.

However, the leading indicators of growth continue to suggest a significant downturn into 2023 is likely.

Importantly, the leading indicators of recession suggest this slowdown could well reach recessionary levels.

This does not bode well for stocks, and suggests continued cautionary risk taking and prudent asset allocation will serve investors well.

What is a recession and how is it determined?

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the recession gatekeeper in the United States. They are the official scorekeepers. Though many believe it is two consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth that defines are recession, this is in fact not the case. Instead, the NBER uses a more subjective approach in declaring a recession. Specifically, the NBER defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.”

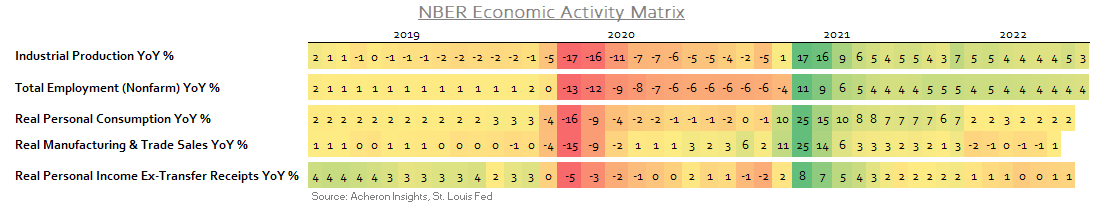

In measuring a decline in economic activity, the NBER uses a number of reliable coincident and lagging economic data points that track all corners of the economy. These data points are made up of nonfarm employment, real personal incomes less transfer payments, industrial production, real manufacturing and trade sales, real personal consumption expenditures and the real average of GDP and GDI. Apart from the latter, these economic indicators are all released on a monthly basis.

The basis for these indicators used by the NBER is the idea that they provide a reliable assessment from all areas of the economy; employment, consumption, income and manufacturing. Admittedly, the NBER has noted they pay particular attention to real personal income less transfer payments and nonfarm employment.

Because these data points are coincident and lagging in nature and are generally not realised until some months after their month of measure, a recession is not able to be determined ex-ante. That is, not until after it has already commenced. Also, it is important to remember coincident economic data does not provide any reliable indication of where the economy is headed, but rather defines the current trend of the business cycle. Though useless from an investment standpoint, it is valuable information nonetheless.

So, with this is mind, let’s dig in to whether we are headed for recession in the months ahead, and if so, the implications for risk assets.

Are we in a recession yet?

As we shall see, I will begin by unequivocally stating we are not in recession yet, and if anything, many of the coincident indicators of the business cycle remain robust.

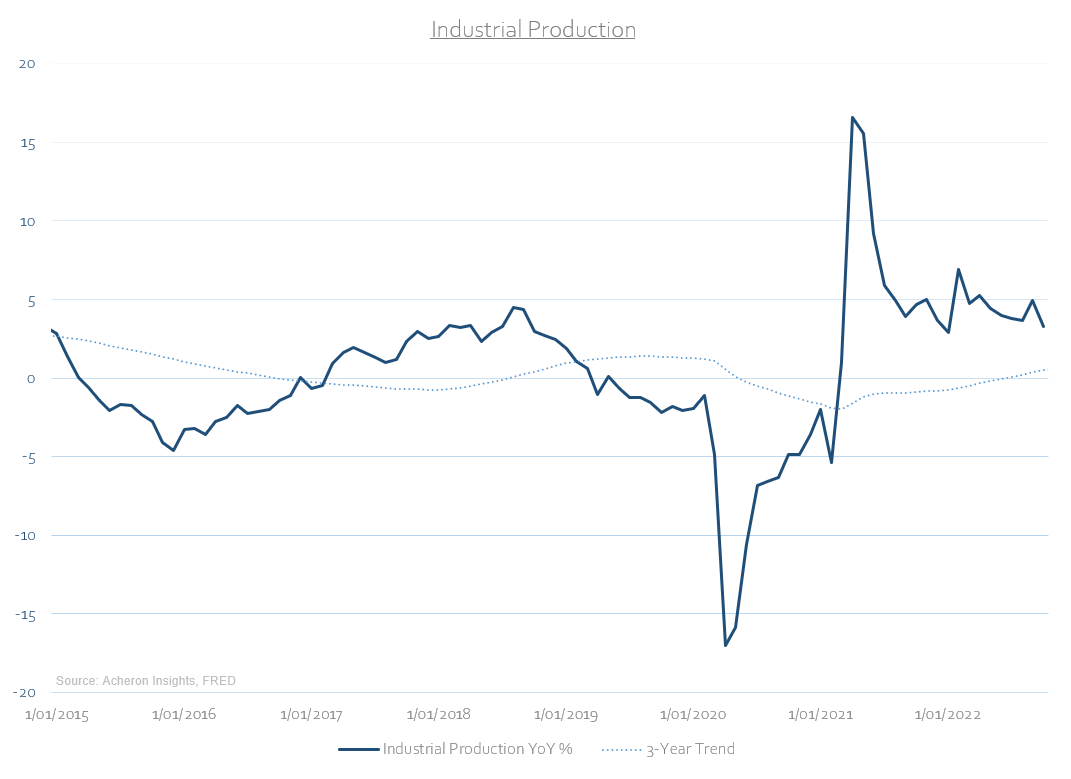

Using the NBER’s framework, we are able to determine where there is currently economic weakness, but also where there is economic strength. Beginning with the manufacturing sector, industrial production growth remains both positive and above trend. Though the growth rate has decelerated materially from the early 2021 highs and continues to modestly decelerate, manufacturing activity remains on solid footing and above trend.

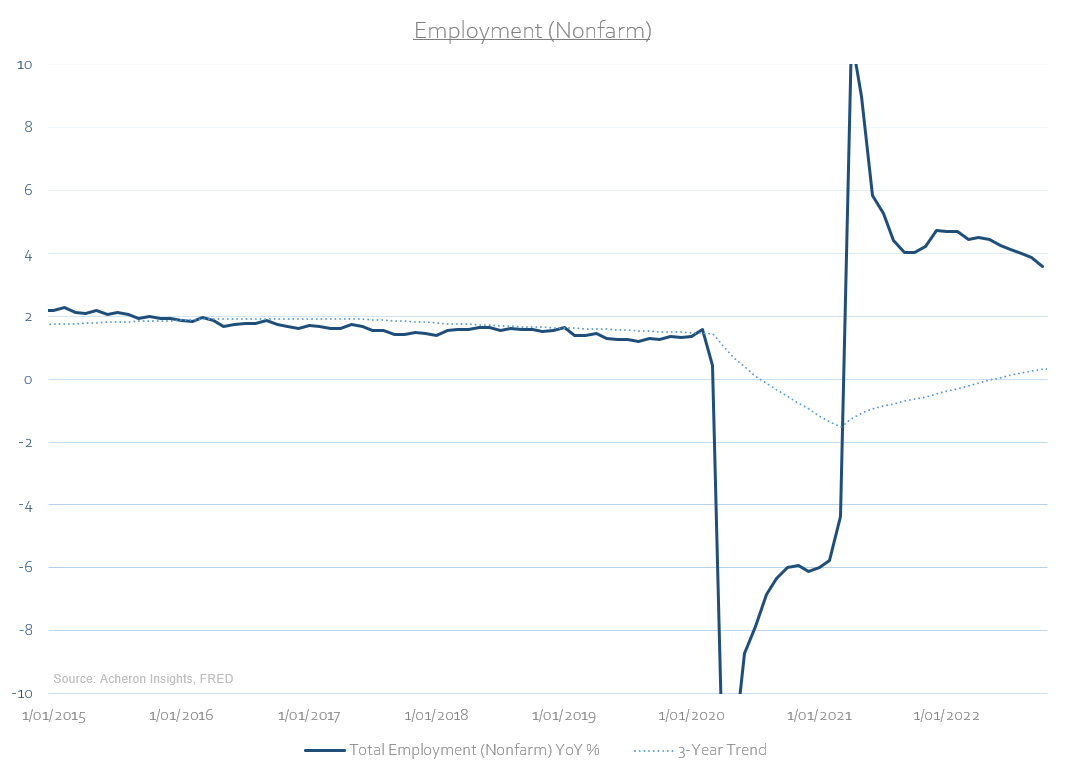

Similarly, the other area of the economy still displaying strong growth is employment. Despite being the most lagging of all lagging indicators, employment growth remains significantly positive and well above trend. This is a key data point to follow given its implications for monetary policy setting. It won’t be until we see a spike in unemployment that we can safely say we are in recession.

Where we are beginning to see cracks in the coincident economic data however are firstly within the area of consumption. As we can see below, both real personal consumption growth and real manufacturing and trade sales growth are below their respective three-year trends. Though the latter was briefly in negative year-over-year growth territory, we would need to see a sustained move lower in both before we can safely say consumption is in recessionary territory.

And finally, real personal income ex-transfer receipts is also below its three-year trend, though this data point has also yet to contract into negative year-over-year growth territory. Interestingly, the direction of for real income growth will be largely determined by whether inflation rolls over faster than wage growth. If so, this could further work strengthen the floor of this cyclical downturn.

Aside from consumption and income, we are still far from recessionary levels for much of the economy at present. This dynamic is perhaps best illustrated below. Until we see a swarth of orange and red, it is safe to assume the US has not yet entered recession.

Extending this analysis beyond the scope of the NBER’s criteria, there are a number of other coincident measures of the business cycle, some of which are perhaps timelier. The ISM Manufacturing PMI is one. Given that the Manufacturing PMI is a timely representation of the trends in the manufacturing sector, it is used by many as a proxy for the business cycle. The headline PMI number ranges from 0-100 and is calculated by surveying a variety of manufacturing executives as to whether they are seeing improvements, no change, or deteriorations in activity. A number above 50 indicates expanding economic activity with below 50 indicating deteriorating economic activity.

As we can see below, the latest headline Manufacturing PMI number was sub-50, clearly indicating contracting economic activity. However, as is evident, a sub-50 PMI reading is not always associated with recession and instead can merely represent a non-recessionary cyclical downturn. Should we see a sub-45 Manufacturing PMI reading in the months ahead, we will then be able to better differentiate whether we are amid a cyclical slowdown or outright recession.

Similarly, another coincident measure of the economic business cycle is the Economic Cycle Research Institute’s (ECRI) Coincident Economic Index. Perhaps a broader measure of the growth cycle than the Manufacturing PMI, but also as timely, by using this metric to identify the current trend of economic activity we can say with a decent level of confidence than when ERCI’s Coincident Economic Index year-over-year growth turns negative, a recession has either just commenced or is imminent. Despite the current trend of growth clearly decelerating at a fairly rapid pace, we are not there yet.

So, are we actually heading for recession?

Astute readers of mine will undoubtedly be aware by now of my outlook for the business cycle. Simply, the leading indicators of growth, both short and long, are all pointing to a significant contraction in economic activity over the next three to six months at the very least. Housing, cost pressures, borrowing costs, and demand/supply imbalances among many others are all suggesting a sub-45 Manufacturing PMI reading is approaching. I won’t go into detail as to the outlook for the business cycle here, as this can all enjoyed within my most recent Growth Cycle Update, but suffice it so the leading indicators of the growth cycle are near uniformly suggesting recession is a significant probability as early as Q2-Q3 of next year. Though nothing is assured in markets.

If we take a moment for reflect on historical causes of recessions in the United States over the past century, and given we know what is causing the current slowdown, this should help to provide valuable context as to the likelihood of a recession in 2023.

Since World War One, the five major causes of recession have been one or more of the following: fiscal tightening; industrial shock and inventory imbalances; an oil/energy shock; aggressive inflation preceding aggressive monetary tightening; and financial contagion asset price crashes. Clearly, we can associate the current environment with overheating inflation and aggressive monetary tightening as well as an energy/oil shock. Whether these dynamics extend to asset price contagion remains to be seen, but it is worth noting that at least two of the five major causes of historical recessions bear much responsibility for the current economic slowdown.

Source: Goldman Sachs

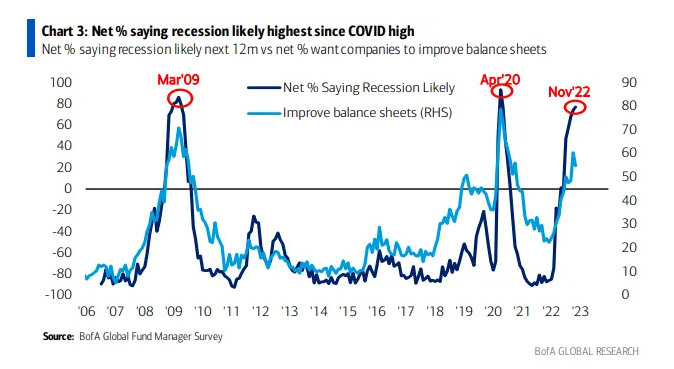

What is also evident is the growing consensus among many that a recession is now an inevitability. Indeed, we can infer this from Bloomberg’s recession probability model, which now equates 100% probability for recession in the next 12-24 months. Likewise, the latest Bank of America (BofA) fund manager survey is too suggesting money managers are becoming certain of an impending recession. As we can see over recent history, they tend to get it right.

Source: Bloomberg via Macro Ops

Source: BofA Global Research

Of course, I’d be remiss for not mentioning what is perhaps the most popular and well documented predictor of recession: the yield curve. Though it is the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yield spread which usually garners most attention, it is actually the 10-year and 3-month Treasury spreads whose predicative capabilities have been most reliable. When both yield curves inflect negatively, the reading becomes only more powerful.

Importantly, when the 10-year less 3-month Treasury spread inverts for 10 or more consecutive trading days, its recession predicting power is flawless. We have entered recession 100% of the time following such a prolonged inversion, with an average lead of about 311 calendar days, or about 10 months. The 10-year less 3-month curve has been inverted for 22 consecutive trading days.

Source: Jim Bianco

So, as we can see, a recession appears likely at some point over the next 12 months. When will we know we have entered recession for sure? When the Fed starts cutting rates. There is no better indicator.

Recession implications for inflation, monetary policy and asset prices

The type of downturn in economic growth that is required to induce a recession will need to be significant. Should this occur, it will have particular implications for both inflation and monetary policy, and I group these two together for good reason. Unsurprisingly, a slowdown in growth will do wonders to quell inflation, although my base case is we see a higher inflation floor than we have seen in the past, as I wrote about recently, inflation will come down significantly over the months ahead nonetheless. For now, inflation momentum is strong with services inflation likely to prove sticky. And, until we see a material decline in inflation momentum, which the impending goods disinflation may well induce as we enter 2023, a recession may be what’s required to bring inflation back near an appropriate level. Until this happens, don’t expect the Fed to cut rates.

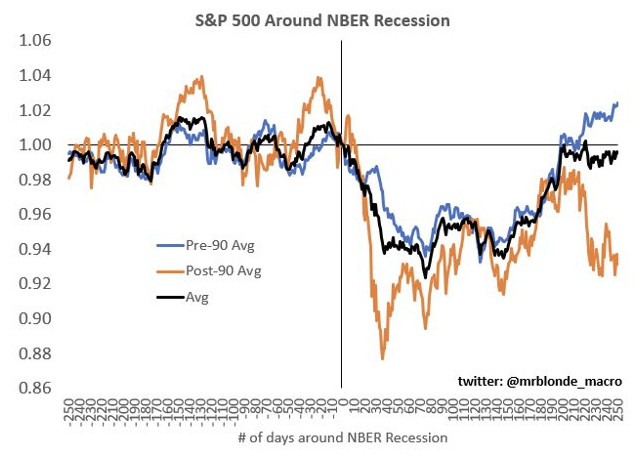

From a stock market and risk asset perspective, the implications of recession are rather more objective. Equities don’t like slowing growth, and they particularly don’t like growth slowing sufficient enough to cause a recession. Recessions and earnings don’t mix. Whilst equities are forward looking to a certain extent, they have historically not bottomed until after a recession has already commenced, as we can see below.

Source: @MrBlondeMacro

Source: Bloomberg

What’s more, it is during the onset of a recession in which equities and risk assets alike are hit the hardest.

Source: Taunus Trust

Unfortunately, due to the fact that recessions are not always known or classified until after the fact, we won’t know this at the time. This is where the forward-looking indicators of the growth and liquidity cycles as well as the Fed’s reaction function are of significant value.

Source: @Mark_Ungewitter

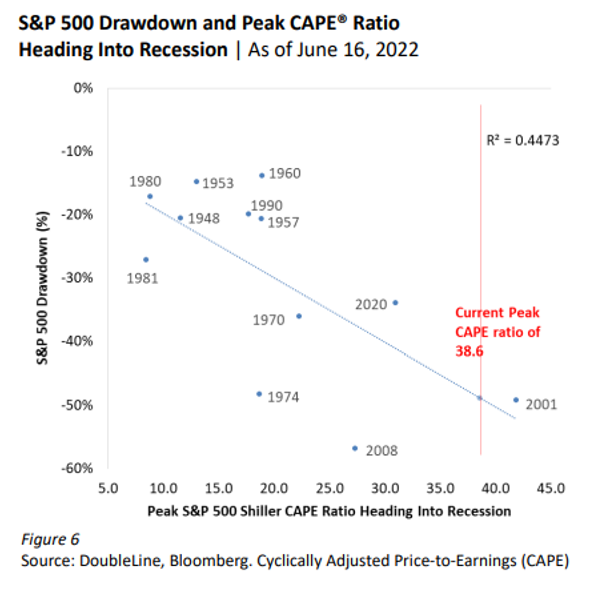

What we do know is the average drawdown for the stock market during a recession is around 30%, with the median recessionary bear market around 24%, per the work of DoubleLine Capital below. With the S&P 500’s peak to trough drawdown this year equating to about 25%, one could argue much of the downturn has been priced in to equities. Whilst this may indeed be the case, it is important to remember the severity of such drawdowns are also a function of the valuations heading in to recession. Regretfully, valuations within US equity markets were near the highest in history at the turn of the year, with the US cyclically-adjusted PE ratio (CAPE ratio) peaking at around 38. As such, should recession indeed become reality, we are likely to see a greater than average drawdown in the S&P 500. When the odds of a recession are rising, best to be cautious with risk taking.

Source: DoubleLine Capital

Source: DoubleLine Capital

Regardless, whether we do enter recession in 2023 or not is perhaps not what really matters. What matters is the leading indicators of the business cycle and liquidity cycle continue to trend lower. Until we see an actual Fed pivot, whereby they move to cut rates, the outlook for risk assets is hazy at best over the medium term. Though investors who have done their research will do well to slowly accumulate shares in attractive companies and assets at attractive prices, an underweight exposure to stocks, pro-cyclical and high-beta risk assets seems prudent. Patience.

. . .

Thanks for reading!

If you enjoyed this article, would you be so kind as to share this around your network or to those who may be interested. Any and all exposure goes a long way to help promote Acheron Insights investment research and is very much appreciated. Thanks again.