Is There Still A Bull Case For Bonds?

Bonds from a growth and inflation perspective

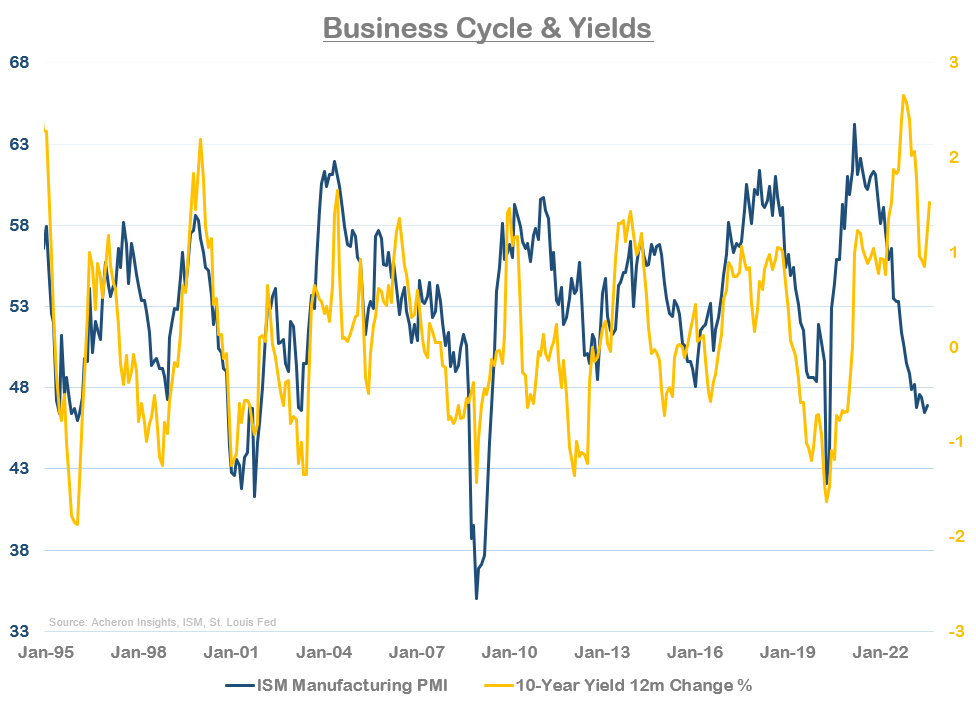

For those who have been bullish bonds and calling for a rally throughout 2023, it has been on the back of falling growth and waning inflation such thesis have been based. By simply looking at the traditional relationship between yields and the business cycle, bond bulls would have expected yields to be 150-200 bps lower by this point in the cycle. This of course has not played out. Despite such potential tailwinds, yields are butting heads with 40-year highs.

It seems the traditional relationship between yields and the business cycle has broken down, at least for now.

Indeed, while my own fixed income asset allocation quadrant has been suggesting an overweight position in duration is appropriate for this stage of the business cycle, this cycle has thus far indeed been different. This asset allocation quadrant is of course based on the traditional relationship between yields, growth and inflation, one that has seen bonds perform so well in prior growth slowdowns throughout this past era of secular stagnation.

But, to be fair, market internals have also been disconfirming the recent highs in yields, as indicators by the likes of the copper to gold ratio and the relative performance of cyclical stocks vs defensive stocks (which are both contributors to this model) have been making lower highs and lower lows while yields do the opposite. Historically, market internals have provided a fairly reliable gauge of where yields should be from a growth and inflation perspective.

However, while growth has been slowing on the whole, the US economy remains robust and resilient, meaning the business cycle overall hasn’t actually been an all-out tailwind for bonds just yet.

Despite the plethora of unfavourable leading indicators of economic growth, the US economy continues to hold steady. Much of this resilience can be attributed to a combination of the following:

Strong household and corporate balance sheets;

Limited consumer exposure to interest rates and tightening credit conditions (particularly given the fixed nature of most US mortgages);

Renewed homebuilding activity as existing home sales has plummeted;

Limited exposure of the US economy to the cyclical manufacturing sector;

Strong and persistent wage growth; and,

The success and residual effects of fiscal stimulus.

And although we have clearly seen a slowdown (and probably recession) in the cyclical manufacturing side of the economy, the services sector is humming along nicely. We can observe this below by examining the recent momentum in a number of key economic data points. Outside of industrial production, growth in consumption, income and employment all remain in expansionary territory.

While the trend in growth is by-and-large to the downside, the economy overall has been running pretty hot, and the expectation we are heading into recession (which is driving many fund managers to allocate to duration) has simply not yet played out.

But I say that to say this. A recession may well be on the cards yet. As I detailed in my recent business cycle deep dive, the evidence continues to point to a slowdown in growth over the coming quarters, which should translate into hard data deterioration at some point in late 2023 or early 2024. This is an outcome that should favour duration at some point in this cycle, but we are not there yet.

Of course, from a fundamental perspective for bonds, growth is only half the story. Inflation and inflation expectations also play a major role in determining the price of interest. Unlike the growth story, the deceleration in inflation has been much more clear cut. Headline CPI has moved sharply lower this year. The latest three-month annualised reading came in at 1.9%, just shy of the Fed’s 2% target.

Of course, core CPI has been far stickier as a result of persistent wage growth, but, the outlook for owners’ equivalent rent (the largest component of both headline and core CPI) suggests the overall trend in core CPI is likely to be to the downside over the next 12 months.

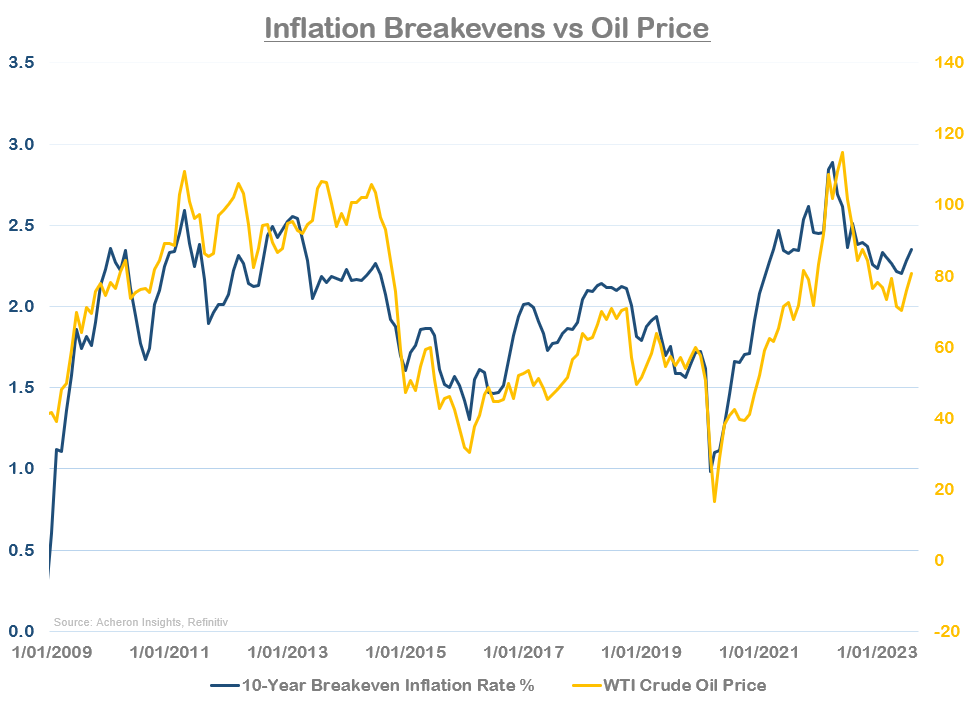

However, I would argue the downtrend in headline inflation looks to be running out of steam. Indeed, as I detailed here, we could well be nearing a point in which many of the cyclical drivers of headline CPI - energy, food and commodities overall - are shifting from inflation headwinds to tailwinds once again. This is certainly a message being corroborated by my composite inflation leading indicator, whose downside momentum clearly looks to be waning and is not suggesting headline CPI reaches the Fed’s 2% year-over-year growth target any time soon.

Of course, whether we do see renewed inflationary pressures show up in headline CPI as 2023 progresses depends much on how far energy prices can rally in the coming months. While I do not think we will see triple digit oil prices this year, the fundamentals within the oil market continue to lead toward the bullish side of the spectrum (as I detailed here).

I would not at all be surprised to see $90-$100 oil in the coming months, an outcome which would once again put increased upside pressure on inflation breakevens (which themselves are highly correlated to the oil price, as we can see below), and thus put upside pressure on interest rates overall.

Sentiment and positioning

The positioning dynamics of the bond market have become rather tricky to decipher in recent times. Bond bulls have been quick to highlight how bearish speculative positioning is towards the bond market, which is currently nearing multi-decade lows.

While speculative positioning is indeed at its most bearish levels in decades (a signal which I would generally lend a great deal of credence), in this case it would be remiss of me if I were not to point out the large potential fault in the signaling power of this data point.

This relates to the basis trade, a popular trading strategy deployed by relative value hedge funds. Such a strategy attempts to profit from dislocations between the pricing of cash Treasuries and that of Treasury futures. During periods when there is demand for Treasury futures from institutional asset managers such as pension funds (which seems to be the case at present, as I shall detail below), then this increased demand can create a dislocation between the price of the underlying itself and that of Treasury futures. This creates an opportunity for hedge funds to lever up in the repo market and buy the underlying while at the same time shorting the futures, attempting to capture the spread. This was a popular investment strategy prior to COVID-19, and we can see these strategies are seemingly once again being deployed by hedge funds by looking at measure such as hedge funds futures positioning (which is heavily short, as we can see above), Treasury repo volumes (which have soared to multi-year highs), as well as asset manager positioning in the futures market (which is heavily long). The Fed itself also recently highlighted how such strategies are seemingly being utilised by hedge funds once again.

Not only does this dynamic suggest institutional capital in the form of pension funds and the like are long bonds, but it also seems to suggest the heavily short speculative positioning in the futures market illustrated above may be somewhat misleading and not actually providing a reliable contrarian buy signal after all.

If we assess discretionary positioning toward bonds through the lens of Bank of America’s Global Fund Manager Survey, we can see that not only are asset managers heavily overweight bonds, but there is also a consensus among them that yields are going to fall from here. Previous instances where discretionary managers were as certain yields were going to fall marked major tops in bonds, not bottoms.

Also confirming this level of bullish sentiment toward long duration is J.P. Morgan’s client survey index.

Unlike what speculative positioning in the futures market is indicating, it appears asset allocations and money managers are actually bullish bonds.

Other measures of positioning are also sending similar messages. The put/call ratio for the 10-year Treasury bond for example remains floored and is not signalling the kind of panic put buying indicative of market bottoms.

In fact, as we can see below, just the opposite has occurred. Call buying on the TLT ETF has skyrocketed in recent months.

Meanwhile, TLT fund flows have been positive for much of 2022 and 2023 as investors pile into the traditional recession trade, while the ETFs short interest is effectively non-existent relative to historical levels.

Again, this is the kind of speculative behaviour generally seen at market tops, not bottoms. Undoubtedly, it appears everyone one is playing the deflationary cyclical game of the last 30 years without understanding the changing structural dynamics surrounding inflation and demand and supply - nowhere is this more evident that in the bond market term premium (more on this later).

Alas, one group of traders we can be sure are actually short bonds and are providing some kind of reliable contrarian buy signal are CTA’s, which are effectively systematic trend following strategies. While not as short bonds as they have been, CTA’s are indeed actually short the market, and, as we can see below courtesy of Goldman Sachs, there is plenty of juice CTA’s can provide bonds should a short squeeze develop at some stage.

Source: Deutsche Bank

Source: Goldman Sachs

It is also worth noting too how pessimistic the media has become toward bonds. While discretionary positioning does not yet reflect this narrative, this level of bearish sentiment in mainstream media is often noteworthy.

Source: SentimenTrader

The supply and demand problem

So, if inflation has been falling and fund managers buying bonds, why do yields continue to go up? Simply put, this is a supply and demand story.

Indeed, I have highlighted in previous articles on the bond market how unfavourable the supply and demand dynamics could be for yields, but, I must admit this bearish force has been far greater than I had anticipated. Unfortunately, this is unlikely to change anytime soon.

Though most will be aware of the fiscal situation the United States currently finds itself in from a Treasury issuance perspective, it is worth repeating. Since running down the Treasury General Account earlier this year, the US Treasury has been issuing new debt en masse, with around $1 trillion of Treasuries forecast to be issued in Q3 and Q4 of this year alone. That’s a lot of supply.

Of course, this is happening at a time when Federal tax receipts are falling and interest expenses rising, two trends which will only exacerbate this dynamic and worsen the Fiscal situation.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve continues to undertake QT and dump additional supply on the market, while foreign investors are themselves also no longer funding US deficits on net (and haven’t been for some years now). As such, it is falling to the private sector buy these bonds.

And, while the private sector has been happy to comply thus far given the attractiveness of US government debt, it is true that when neither the Fed nor foreign investors are willing to provide the required level of demand, “in the absence of demand, supply sets the price.” Per the work of Totem Macro below, what this means is historically, excess supply has had a far more meaningful impact on pressuring yields higher than would be the case when the Fed was willing to support the market via QE and foreign investors were willing to finance US deficits.

Source: Totem Macro

These excess supply dynamics remain a continued threat to the bond market. But it unfortunately doesn’t end there.

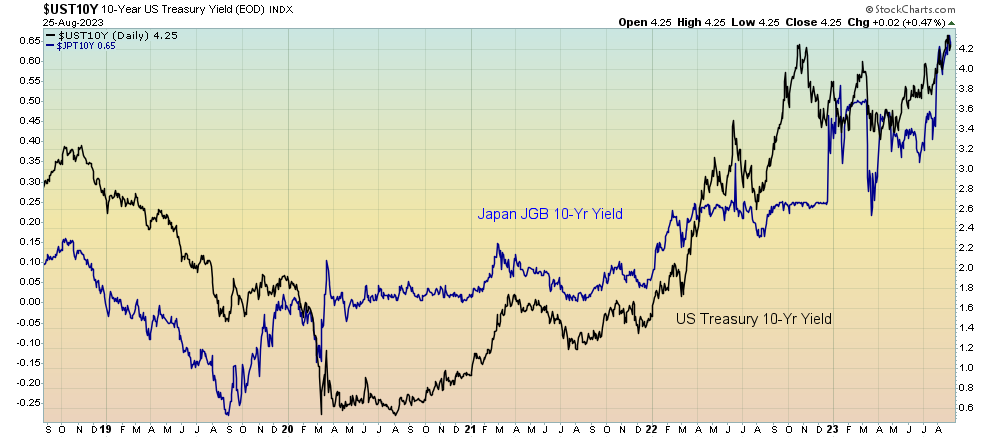

Japanese investors are the largest foreign owners of US Treasury securities. Japanese insurance companies and pension funds represent some of the largest pools of capital in the world, and US bonds are one of their primary holdings. So, when the Bank of Japan makes alterations to its yield curve control policy, this can have big implications for Japanese capital flows.

Indeed, they have recently done just that, widening the 10-year JGB trading band from 50 bps to 100 bps. And, as noted recently by the FT, with '“yields going up in Japan, the risk is that Japanese investors will now begin to sell US fixed income and start buying higher-yielding Japanese fixed income. This is a big deal for global fixed income markets because Japanese investors are the biggest foreign holders of US Treasuries, and they also own significant amounts of US credit.”

We can see this dynamic in play by looking at the correlation of 10-year US Treasury yields and 10-year Japanese government bond yields. As JBG yields rise, Japanese capital allocators are incentivised to sell foreign USTs and buy domestic bonds.

The depreciation of the Yen relative to the USD also exacerbates this dynamic, as many Japanese investors hedge their FX exposure when investing in foreign debt assets. So, when the dollar/yen FX rate rises (USD appreciates relative to the Yen), hedging costs increase and domestic yields can become more attractive even if the yields are lower than UST yields. This dynamic helps to explain why the USD/JPY FX rate (black line below) is so closely correlated to US yields (blue line below).

This dynamic is perhaps better illustrated by comparing JGB yields relative to FX hedged UST yields, as we can see below. The additional yield pick-up for Japanese investors when investing in USTs is much lower than the JGB yield when accounting for the hedging costs associated with foreign investment.

Source: Bloomberg via Luke Gromen/FFTT

This is the threat of the great repatriation of foreign capital. All else equal, rising JGB yields and a strong dollar incentivises Japanese investors to repatriate capital to finance Japanese deficits instead of US deficits, a dynamic which will only serve to further reduce demand for US government debt securities (at least at current rates).

But once again, the story doesn’t end there. Another spike in oil and energy costs could again result in capital flows from energy importers out of USTs and into domestic assets in order to defend their currencies - as rising energy costs lowers current account balances thus depreciating the currency - another risk to duration should energy costs (i.e. oil) start to rise again. Such flows are effectively equal to additional QT.

Should the USD strengthen, this also gives reason for foreigners to continue to sell USTs to strengthen their own currencies (as the dollar trends to go up when Fed is conducting QT and the private sector must adsorb the debt while the foreign sector is selling). The recent devaluation of the Chinese yuan speaks to this risk, with Reuters recently reporting that Chinese banks are trying to defend the CNY by selling USDs/USTs.

As we can see, the supply and demand imbalance clearly indicates their remains upside risk for yields and downside risk for bonds, regardless of the macro fundamentals for duration. These are very important factors at play that have not been anywhere near as prominent in recent times where the fundamentals favoured duration.

Technicals

From a technical perspective, the 10-year yield is at an interest juncture. After butting heads with recent resistance just shy of 4.4% and completing a daily 9-13-9 DeMark sell signal, this recent move higher in yields clearly looks to be running out of steam. Given the level of bearish media sentiment toward bonds at present, I suspect we will see this correction continue to play out over the next month or two, though I would be surprised if yields were to retrace all the way down to their major support level around 3.4% anytime in the near future. Indeed, barring any imminent crash in equities, recession or market event that sees the return of QE, it is hard to argue against this being a chart that looks like it wants to go higher overall.

The structural risks for bonds

While what I have discussed thus far has primarily focused on the cyclical outlook for bonds, it is worth highlighting some of the secular risks for the bond market that could see yields move much higher over the medium to long-term.

This dynamic is most aptly examined through the lens of the term premium, which represents the additional compensation investors receive for holding a longer dated bond (i.e. 10-year Treasury) until maturity as opposed to continually investing in one year Treasuries and reinvesting the proceeds each year upon maturity. In theory, the term premium should account for the additional duration and inflation risks associated with locking up capital for a long period of time.

As it stands, it appears the term premium for 10-year Treasuries is not at all reflecting any kind of structural risks facing markets. Estimates of the term premium suggest it is still negative as investors are yet to demand any kind of meaningful compensation for actually bearing the additional risks for being long duration in a world of changing secular trends, whereby inflation and geopolitical risks are at multi-decade highs.

We can see this below by comparing the term premium to various forms of long-term inflation expectations.

The same can be said of inflation uncertainty, which has clearly yet to be accounted for by fixed income traders.

Source: Simon White, Bloomberg

Even the outlook for debt issuance by the US Treasury and the excess supply this is set to bring to the market is yet to be fully accounted for in the term premium.

On a structural level, it seems clear there are a number of reasons why yields could go higher from here, or at least average a higher level that what we have seen during recent decades. These are dynamics all bond bulls should keep in mind.

Concluding thoughts

Summing it all up, there are clearly a very large number of factors at play here that are contributing, or attempting to contribute, to the movement in bond prices and yields. The economic resilience thus far has resulted in any kind of material growth slowdown or recession being pushed back, meaning the macro conditions are yet to turn truly favourable for bonds. Likewise, while the cyclical inflation trend has been to the downside for most of the past 12 months, there are signs suggesting inflationary pressures could again re-emerge as we close out 2023.

Meanwhile, the supply and demand story for bonds remains as bearish as ever, with excess issuance by the US Treasury and the potential for the repatriation of foreign capital both serious risks that could lead to higher yields.

Will we get a cyclical bond rally at some stage? Most probably, but the timing here is very difficult given the bearish factors in play. A significantly rally in bonds will probably require a material stock market crash, recession, or the resumption of QE. This is particularly true given how discretionary positioning toward the asset class is seeming on the bullish side. For now, being long duration at present is not the right risk/reward trade investors should be looking for, particularly given the attractive yields on offer from the short end of the curve. After all, we now live in a world where you can be paid to wait.

. . .

Thanks for reading!

If you would like to support my work and continue to allow me to do what I love, feel free to buy me a coffee, which you can do here. It would be truly appreciated.

Regardless, feel free to share this with friends and around your network. Any and all exposure goes a long way and is very much appreciated. Thanks again.