The Labor Market Is Still Historically Tight

Summary & Key Takeaways

With wage growth still strong and unemployment low, the labour market is still historically tight. For now.

This will continue to pressure policy makers to remain hawkish and likely lead to a policy error, not for the first time.

Looking forward, the leading indicators of unemployment suggest we are likely to see a material rise later this year, while the leading indicators of wage growth suggest a deceleration is also likely.

This will have significant implications for inflation, whilst also allowing a dovish Fed pivot, eventually.

In case you’d forgotten, the labour market is still historically tight

Despite being a lagging economic indicator, understanding the outlook for both employment and wage growth is important for all investors as the flow on effects from these trends are considerable. In particular, the movements in employment and wage growth have significant influence on the monetary policy decision making process of J-Powell and his associates at the Fed, which itself is a significant driver of both the liquidity and growth cycles, and thus asset prices.

As it stands, the dynamics within the labour market are not representative of recessionary conditions nor are they at levels that beget easy monetary policy. This is true of both the unemployment rate and wage growth.

Despite all the talk of recession, which may be true, the labour market is still historically tight. The gap between job openings and the number of unemployed persons remains far beyond any level seen in decades. Although openings appear to be normalising at long last, the number of unemployed persons is yet to show any sign of the impending economic slowdown.

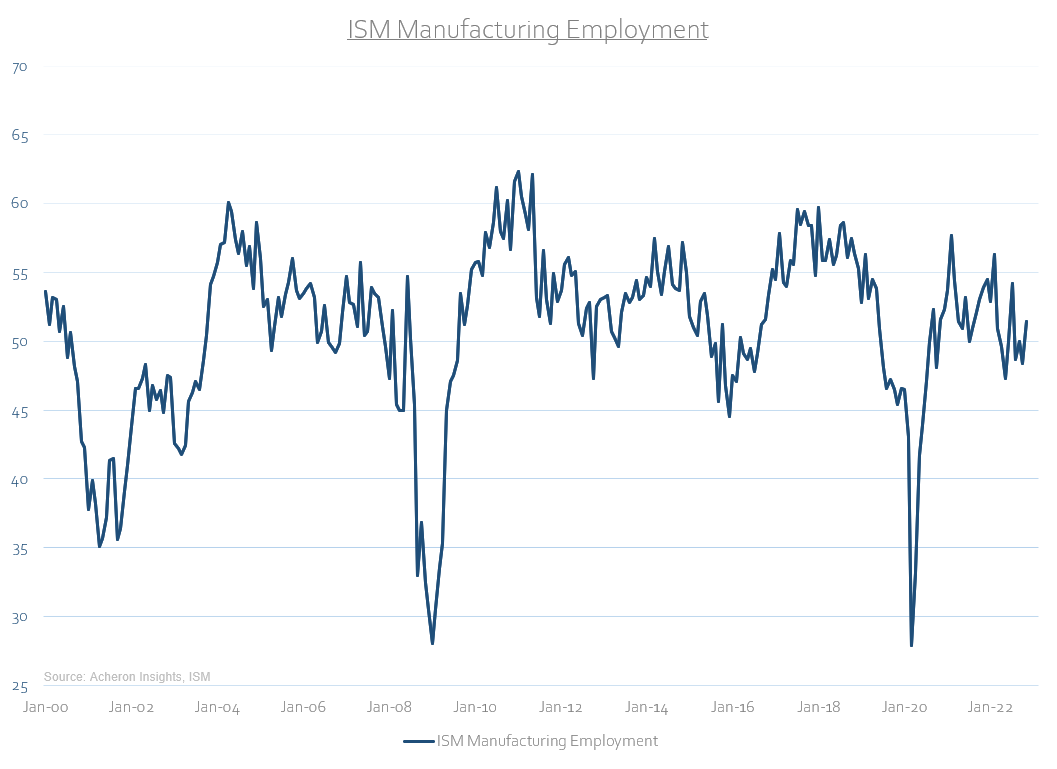

Importantly, employment with the cyclical areas of the economy is holding up well. The Manufacturing Employment subindex of the ISM survey remains above 50 - which is expansionary territory - while the growth in employment from the manufacturing and construction sectors are both firmly positive and still above levels seen only 12 months ago. Although only a small part of the US economy, manufacturing in particular is one of the major cyclical drivers of the business cycle, while construction is heavily linked to housing, which itself is a significant driver of economic growth. Economic slowdowns usually see these areas of the employment complex slow first, but this is yet to occur to any material degree.

Likewise, initial claims for unemployment too provide a timely insight into employment trends, and at present remain near cycle lows. Despite the significant number of layoffs seen within the tech sector over the past 12 months, they have been very much contained within the tech sector itself and are not yet representative of unemployment contagion.

Unsurprisingly, for these reasons we have yet to see wage growth subside, with the Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker still reporting a median growth rate of over 6% pa. This is still materially higher than at any point during the 21st century.

As it stands, employment and wage growth trends are not consistent with an economic recession. However, they are most definitely suggestive of late cycle dynamics. When unemployment rises, it tends to rise hard and fast. This is where the leading indicators of employment and wages come to the fore.

The unemployment rate will rise… eventually

If we delve deeper into the current dynamics within the labour market, as well as the leading indicators of employment, there is plenty of evidence to suggest a rise in unemployment is likely.

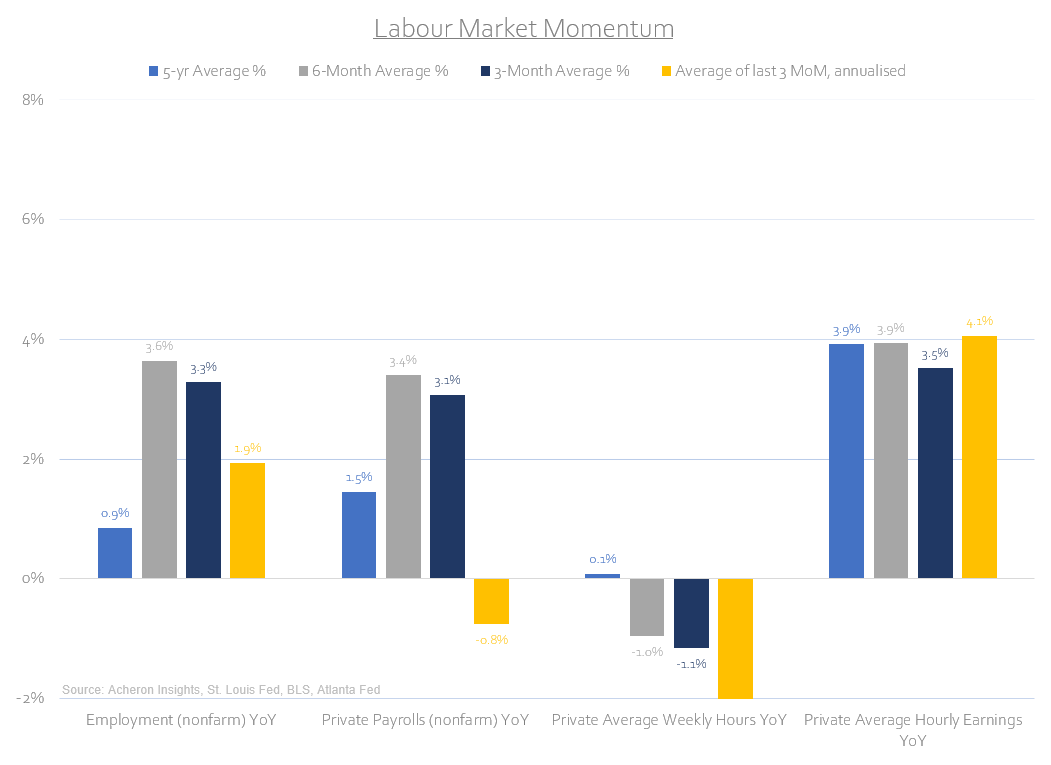

In terms of momentum, the past two to three months of data points are showing signs of weakening. While the three and six-month averages in employment growth, private payroll growth, average weekly hours growth and average weekly earnings growth remain fairly strong across the board, the trend is slowing (with average hourly earnings being the exception).

Although employment within the manufacturing sector remains strong for now, when we assess the sector via overtime hours worked, we can see there are cracks beginning to form under the surface. With the manufacturing sector clearly suffering from an economic growth perspective (the sector in which the leading indicators of growth are perhaps most depressed), it appears as though overtime hours is beginning to reflect this reality. As such, we should begin to see this trend show up in the overall manufacturing employment data in the coming months.

If we turn to the dynamics within the small business sector, similar trends are evident. Small businesses represent roughly 66% of all new job creation and contribute to around 44% of total US economy activity according the US Small Business Association. As such, the employment trends therein are highly influential to the overall movement in employment and wages.

Two sub-categories within the NFIB Small Business Survey tend to be fairly reliable leading indicators of the overall rate of unemployment; these are the ‘plans to increase employment’ and the ‘good time to expand’ responses. As we have seen with many survey and soft data points in recent times, both have fallen significantly of late and suggest a material rise in unemployment at some point in 2023 is likely. Small businesses are feeling the pinch and as such this will eventually result in layoffs, or a reduction in new hires.

The same trend can be observed when we assess consumer sentiment and consumer confidence via the University of Michigan and Conference Board surveys. Both tend to lead the unemployment rate in an inverse manner and to portend a rise in the latter is forthcoming.

Another soft data point confirming this outlook is the NAHB Housing Market Index. Given how significant the slowdown within the housing sector has been, along with the significant drags on economic growth that have resulted, it appears inevitable these dynamics will find their way into the labour market eventually.

However, while these survey data points are of significant value, it is important to consider the idea that they have perhaps been skewed to the downside by inflation, thus their efficacy and forecasting capabilities should be taken with a grain of salt. For unemployment to rise to a material degree, we would need to see the business cycle truly accelerate to the downside, which has yet to occur and it appears may not do so until at least Q2 of this year.

One way to identify this is by simply glancing at the yield curve. Whilst inversions are suggestive of recessions anywhere from six to 24 months out, it is the subsequent steepening of the yield curve following an inversion that usually correlates to an actual recession occurring, along with a material rise in unemployment. We are not there yet.

But, we are certainly heading in that direction. With the leading indicators of the business cycle suggesting a Manufacturing PMI reading of around 35-45 is likely at some point this year, employment will eventually follow suit. Remember, laying off workers is generally a last resort for businesses.

Wage growth is peaking and should roll over soon

Given the labour market remains tight, wage growth too remains strong. However, it is the rate of change that matters for both markets and policy makers alike. As such, a deceleration in wage growth is likely to have material follow through effects on monetary policy decision making as well as overall inflation, particularly on the sticky services side.

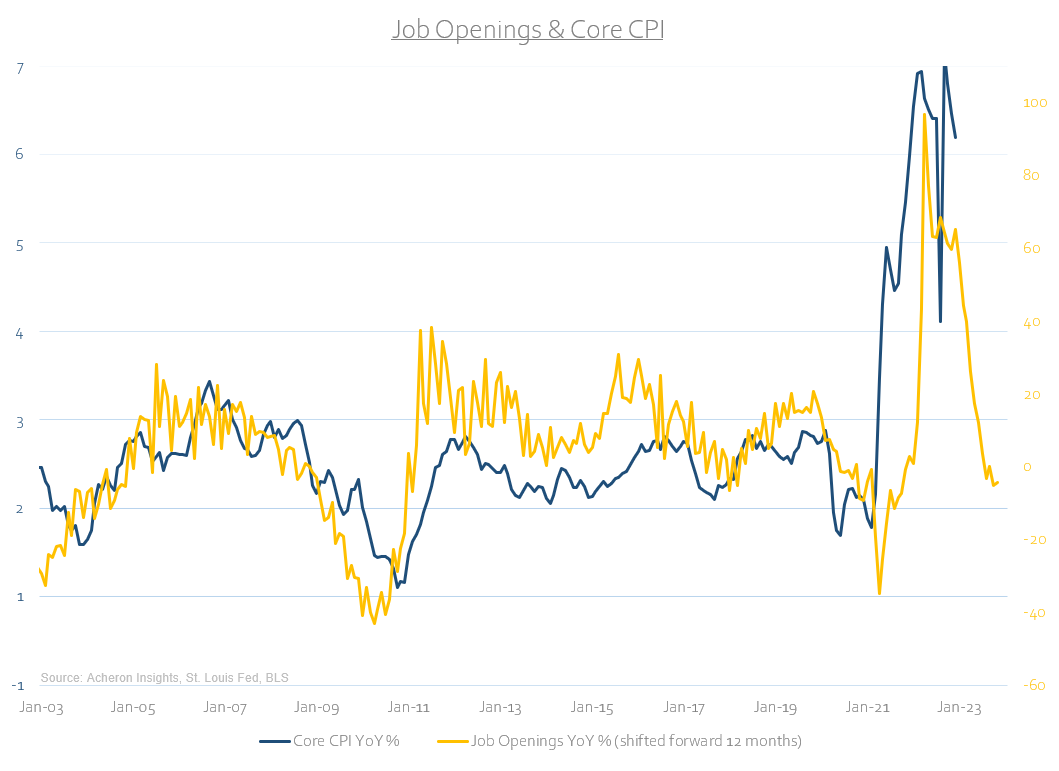

For the most part, the leading indicators of wage growth suggest a decline is imminent. Both the year-over-year rate-of-change in the quit rate and ratio of openings versus unemployed tend to lead wage growth by around nine months respectively. Both have rolled over hard.

These trends make sense intuitively, a rising quit rate occurs when workers voluntarily leave their jobs in order to move to higher paying roles elsewhere, while a rising ratio of job openings versus unemployed persons indicates a shortfall of workers and suggests employers need to increase compensation offers in order to attract workers. These trends saw wage growth skyrocket during 2022 and appear to now be working in reverse.

We can see similar dynamics also at play within the small business sector. Per the NFIB Small Business Survey, the trends in both ‘job openings’ and ‘compensation plans’ generally lead wage growth by around six months, and are too beginning to move lower.

Another important driver of employment has been the movements in asset prices in recent times. As I detailed in-depth here, as a result of decades of economic stagnation and a reliance on growth through easy monetary policy we now live in a highly financialised economy. What this means is that movements in asset prices - particularly stocks and housing - have a significant impact on real economy trends such as employment, consumption, economic growth, Federal tax receipts and corporate capital expenditures.

For employment in particular, the feedback loop between the two is striking. Easy monetary policy leads to higher stocks; higher stocks lead to more job openings; more job openings lead to higher inflation and low unemployment; higher inflation and low unemployment lead to tighter monetary policy; tighter monetary policy leads to falling stocks; falling stocks lead to falling job openings; falling job openings leads to falling inflation and rising unemployment; falling inflation and unemployment lead to easy monetary policy; easy monetary policy leads to higher stocks and so on. This is what happens when easy monetary policy dominates, corporations will do anything to keep earnings elevated, from cutting capex to laying off workers.

Right now, job openings should continue to follow stocks lower, and thus wage growth should follow suit.

If employment is such a lagging indicator, does it even matter?

It is absolutely true that employment, much like inflation, is a lagging economic indication. It does not tell us where the economy is headed but instead illustrates the current trend in economic growth and activity, as well as signifying where we currently reside in the business cycle. In isolation, employment trends and wage growth provide little value in investment decision making nor asset allocation. However, because employment and wages are one half of the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices, it is though their reaction function to the trends within the labour market that have significant implications for the future direction of monetary policy, and thus liquidity, economic growth and asset prices. Regardless of how susceptible the Fed’s actions are to policy errors in using such lagging economic data, this is the world we live in and thus why the labour market is important to monitor.

Indeed, with wage growth still strong (for now), the Fed continues to be worried about sticky services inflation, which itself is primarily driven by wage growth. If the direction in the growth of job openings continues to lead core-CPI, while wage growth eventually rolls over as the leading indicators suggest, then these trends ought to soon turn from services CPI tailwinds to headwinds. It is however too early to tell how disinflationary the impulse in wages will be, so expect a moderately hawkish Fed for some time still.

Furthermore, it is also important to remember an unemployment rate of 3.5% is not commensurate with dovish monetary policy. Regardless of the dynamics within the labour force participation rate skewing such numbers of the downside, the current rate of unemployment is not yet near levels that have historically resulted in the Fed pausing rate hikes, let alone cutting rates altogether.

What the current rate of unemployment does signify however is that we are in the latter stages of the business cycle. Unsurprisingly, such conditions do not portend positively for the stock market.

Source: Peter Berezin - BCA Research

Likewise, strong wage growth will eventually find its way through to profit margins. Over the long-term, profit margins are highly correlated to labour costs (i.e. wage growth). With the labour market still secularly tight and wage grow strong, history suggests profit margins will eventually need to adjust downward to reflect these higher costs of labour. As I discussed here, this will have significant implications on earnings growth, but is likely still a story for Q2-Q3 at the earliest.

Source: John Hussman - Hussman Funds

For now, the labour market is still tight. Unemployment is low and wage growth is strong. As a result, this will continue to pressure policy makers to remain hawkish and likely lead to a policy error (again). Forward looking however, the leading indicators of unemployment suggest we are likely to see a material rise later this year, while the leading indicators of wage growth suggest a deceleration is also likely. A recession will of course exacerbate these trends, which are likely to have material implications for inflation, and eventually, allow the Fed to ease monetary policy. But, we are not there yet.

. . .

Thanks for reading!

If you would like to support my work and continue to allow me to do what I love, feel free to buy me a coffee, which you can do here. It would be truly appreciated. .

Regardless, feel free to share this with friends and around your network. Any and all exposure goes a long way and is very much appreciated. Thanks again.